“Let’s show her the big mouth,” Marie Twitchell said to her dad. Wilson Twitchell smiled and shifted the angle of his boat motor slightly so they could take me there. We were on a small skiff, navigating a web of tundra lakes, rivers and sloughs in Southwest Alaska near the Yup’ik village of Kasigluk. At 11 p.m., the midsummer sun was beginning to set, and the temperature was dropping; I braced myself against the wind. Wilson, his wife, Bertha, and four of their seven children — Angela, Rochelle and Yeako, as well as Marie — all sat snugly on the boat’s bench seats, along the floor or in a camping chair. Snorty, their small black dog, circled our feet, ready to bark at the ducks that flew alongside us.

Before long, we rounded a corner and I saw a sloping tundra knoll protruding from the water. A dark, gaping horizontal hole was eroding right out of it, looking very much like a big mouth. As we drew near, the smell of decay grew strong. Thick mud dripped from the ceiling into the water. The cave was shallow but dark, except where the light caught a patch of ice deep within, shining and melting in the exposed air.

Permafrost. For all the times I’ve walked over the top of it or spoken its name, it’s a rare slice of earth to actually see, the ancient ice and frozen ground that underlies so much of Alaska, including where I live in nearby Bethel. It’s a constantly shifting presence that forces us to level our homes, makes constructing basements nearly impossible and now is quietly thawing in the warming climate — taking homes, schools, boardwalks and even graveyards with it.

Climate change and thawing permafrost are impacting both landscapes and lifestyles in and around Kasigluk. The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta is made up of thousands of tundra lakes, ponds and silty river estuaries. Erosion and shifting land have always been a part of life here, but climate change is ratcheting up the speed and intensity of these natural processes. Along with that, forced assimilation of Yup’ik people, who traditionally moved between seasonal camps, led to the construction of permanent infrastructure on unstable land.

It’s a rare slice of earth to actually see, the ancient ice and frozen ground that underlies so much of Alaska.

Wilson Twitchell stood up on his boat, pointed out toward the eroding tundra and recalled a visit to this very spot two years earlier with his kids, looking for moose. “We were able to park (the boat) right below it and just walk straight up that knoll there,” Wilson said. “You can’t do that anymore — it’s gone.”

TWO DAYS LATER I stepped off the boardwalk in Kasigluk and into the Twitchells’ home. A river, the An’arciiq, commonly called the Johnson River, divides Kasigluk into two halves, Akiuk and Akula. Akiuk is older, and the land beneath it is sinking into tundra marsh and eroding into the river. Akula, the newer side of the village, sits much higher, on a more stable piece of land. The Kasigluk Traditional Council is working to expand Akula and relocate the entire community there. But the speed at which Akiuk is disappearing far outpaces that at which the federal government funds the relocation of communities facing climate catastrophes. Winter freeze-up provides seasonal stability in Akiuk, but for six months of the year, many homes are in danger of flooding or falling into the river.

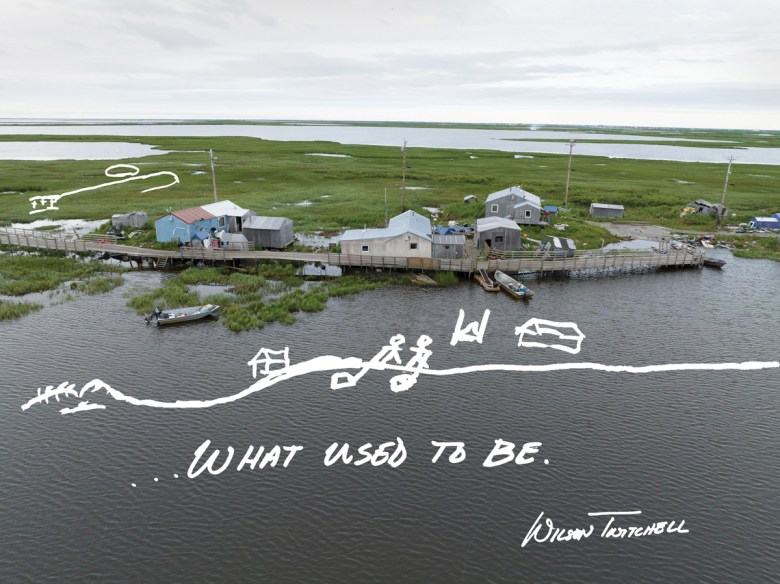

Bertha and Wilson Twitchell stand outside their home, where Wilson grew up. On a photograph of part of present-day Akiuk, Wilson drew an image of what the land was like when he was young: Grass and dry land surrounded the house, stretching at least 80 feet to the riverbank, where he remembers playing with toy boats (above). Now, when the water is particularly high, the house is nearly an island with the Johnson River running under the front and tundra ponds encroaching on the back. “Three or four weeks ago, we were hearing some lumber and waves crashing underneath the kitchen,” Wilson said. “Every time a boat would pass or we were getting west winds, we were hearing some wood knocking that was floating on top of the water, trapped underneath the floor.”

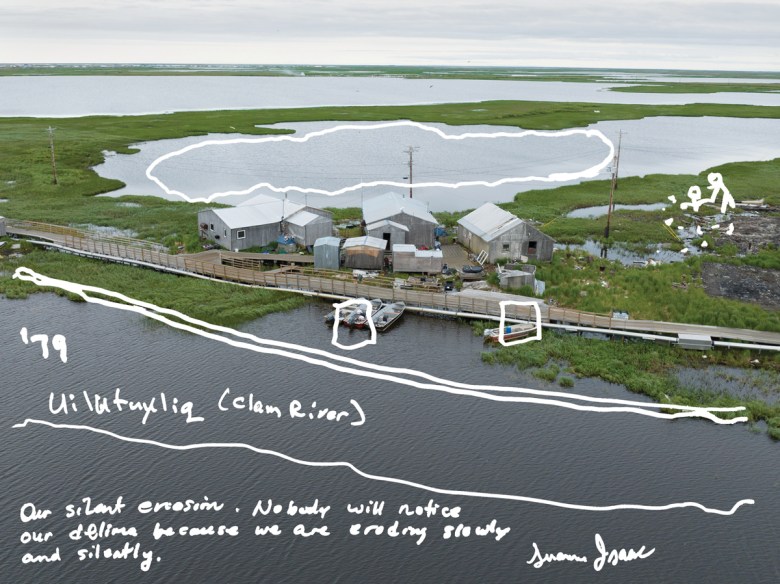

Susanna Isaac stands on an old dock in Akiuk that connects to the community’s boardwalks. “We can’t even walk off them or we will sink. It’s too swampy,” she said. It wasn’t like that when she was growing up. “There used to be a path of mud, hard mud, and we’d walk back and forth to houses.” Isaac sketched memories of how the land has changed over time in Kasigluk (above). “I remember we used to play during recess down where those boardwalks are now,” she said. “We used to pick berries, a whole lot of us from the village, and it never used to seem to run out. And we’d be picking grass, too, from here, for our winter shoes. But the land was, I would say, pretty wide at that time. Compared to today, most of it where we used to stomp around is all gone.”

Kasigluk is not alone. Erosion, permafrost thaw and flooding are happening with more frequency and intensity in communities throughout Alaska. The nearby village of Napakiak is losing up to 100 feet of land a year to erosion, while out toward the Bering Sea coast, Newtok is actively relocating due to the encroaching Ninglick River. In Bethel, spring flooding is common in my low-lying neighborhood — but now we also prepare for fall floods due to stronger, scarier storms like last year’s Typhoon Merbok.

“Nobody sane would be staying here today. We really need to relocate now.”

Down the boardwalk at the far end of Akiuk, Susanna Isaac, a retired teacher, talked about the changes she’s seen in Kasigluk. The tundra knolls where she gathered eggs as a child have collapsed into marsh, and the hard-packed dirt she used to play on is under water. Isaac sighed and looked out the window as she spoke.

“Nobody sane would be staying here today,” Isaac said. “We really need to relocate now. All we’re waiting for is our house to fall, and if our house falls, then we have no choice but to move away. Not here, because housing’s not available. So we have to move away.”

While visiting Isaac the evening before, I had watched her son working outside to level one of their outbuildings. Her kids and grandkids sorted and packed dried fish on the kitchen floor.

“My plan is to move to Anchorage, where I know my daughter will help us settle in,” Isaac continued. “But if they do give us land here, we’d gladly stay because this is where we grew up. The hunting, the picking berries … all of our Native ways are here.”

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Katie Basile is a documentary photographer and filmmaker with a focus on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta region of Alaska. She grew up in Bethel, Alaska, and continues to live there today with her partner and two young sons.

KYUK reporter Nina Kravinsky contributed to this story.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline Unstable Earth.