Editor’s note: This story contains details about violent events suffered by missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

A long dirt road leads to Violet Soosay’s home in Maskwacis, a Cree community about an hour’s drive south of Edmonton, Alberta. There, in her living room, Soosay smudged and then settled into an armchair, resting her legs on an ottoman. Her moccasins tapped the air as she spoke about her aunt, Shirley Ann Soosay.

Both women are members of the Samson Cree Nation, and both were born in Maskwacis. Violet remembers her aunt, who was 15 years older, as gentle and considerate. When she was a girl, Violet said, Shirley “was the only one I would allow to comb my hair.” She remembers her aunt watching over her as she played with the barn cats: “Barn cats like that are pretty wild, but she would pick out one that I would be able to play with.”

Like many in their family, Shirley and Violet both attended the Ermineskin Indian Residential School. Starting in the mid-1800s, Canada and the U.S. removed hundreds of thousands of children from their homes and sent them to residential schools, determined to extinguish their Indigenous cultures and languages. There was rampant physical and sexual abuse, malnourishment and disease at the schools, and thousands of children died. One of Shirley’s former classmates said that both she and Shirley were abused and forbidden to speak Cree.

When Shirley was in her 20s, in the late 1960s, she moved to Edmonton, the nearest big city, seeking work. But every holiday, no matter where she went, she always sent her mother a card. In Vancouver, she met and married a man and had two boys, but the marriage ended badly, as Violet recalls: Shirley’s husband kicked her out and called child welfare, and the children were placed in foster care. In 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) described the child welfare system as a direct and racist legacy of residential schools, with a history of disproportionately separating Indigenous children from their parents.

For Shirley, losing her children was not only devastating; it was disgraceful. “Shirley comes from a very strong matriarchal society,” Violet said. “The idea of losing your children was shameful, it was unbearable, intolerable.

“It destroyed her,” Violet said. “She started drinking and eventually she started taking heroin.”

In 1976, Shirley gave birth to another child, who was taken from her at the hospital by child welfare, Violet said.

The last time Violet saw her aunt was when Violet was a teenager. Shirley came home for Violet’s father’s funeral. Violet remembers that her grandmother — Shirley’s mother — warned Shirley not to travel alone. “It’s a reality in Indian Country,” Violet said. “When you are an Indigenous woman, you’re prone to be put in a situation where it’s a life-and-death kind of thing.”

Violet suggested her aunt get a tattoo of her own name, so she could be identified, in case she ever went missing.

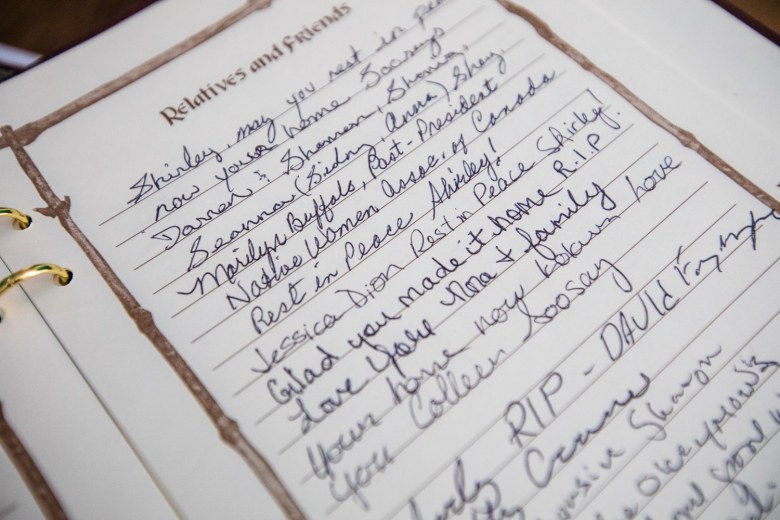

After the funeral, Shirley left again for the West Coast, though she continued to send her mother cards. Then, around 1980, the cards stopped. “No birthday card, no Christmas card, nothing,” Violet said. “And my grandmother knew right away that something was wrong.” She sat by the phone, waiting to hear from her daughter. And not long after, speaking in Cree, she asked Violet and an auntie to “bring her home.”

“My grandmother knew right away that something was wrong.”

“There was no saying no, especially to a matriarch,” Violet said.

So Violet Soosay went to the police. But there, she said, she was met with glaring racism. “She’s probably just another dead Indian,” she recalls them saying. No report was ever filed. With no help from the police, the family searched, making regular road trips to Vancouver and Washington state. They looked in hostels, hospitals and cemeteries, searching grave by grave, either for Shirley’s name or for “Jane Doe” — the name given to unidentified women.

It would take 40 years and a controversial DNA tool to finally bring Shirley Soosay home to Maskwacis.

Shirley Soosay became one of the first Indigenous Jane Does in North America to be identified through Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG), a tool used by Canadian and U.S. law enforcement agencies. Her family was one of the few of the thousands of Indigenous families in the U.S. and Canada with missing loved ones who finally achieved any closure.

Investigators believe this new DNA process has huge potential to solve cases involving missing Indigenous people. IGG comes with risks, though. The more people share their genetic profiles with online databases like GEDmatch, the more effective the technique becomes. But experts warn that the private companies that own these databases, or the investigators who use them, could use the information to violate people’s constitutional rights. Ultimately, it could become a new kind of colonial extractive industry, amounting to a loss of genetic sovereignty for Indigenous communities. Law enforcement agencies and groups that use IGG do not always disclose how the DNA data will be used, while recent database breaches by hackers and genealogists reveal how the lack of regulatory oversight leads to violations. And, for some Indigenous communities, there may also be a level of risk to traditions and customs. All this creates a new risk to Indigenous self-determination.

A FEW YEARS AFTER Shirley Soosay disappeared, two teenage girls in Leicestershire, a county in the East Midlands of England, were raped and murdered by an unknown attacker. Police sought help from Alec Jeffreys, a geneticist from the University of Leicester who had recently discovered a DNA-matching technique that he believed could be used to solve crimes. Investigators tested DNA samples from semen retrieved from the girls’ bodies against the DNA from 5,500 blood samples collected from local men. At first, no obvious match was found, but in 1987, after a tip that one man had faked his sample, investigators arrested him and matched his DNA to the crimes. It was the first case in which DNA was used to solve a crime.

In the decades since, geneticists have refined the method, which compares short repeating segments of DNA. Today, it is commonplace in police work. In the U.S., police can enter DNA from a crime scene into a government database of samples taken from people who have been arrested or convicted of crimes. The database is known as the Combined DNA Index System or CODIS. There are regulations concerning how and when CODIS can be accessed, and the database is subject to laws and oversight.

Then came Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG). The new method is more sensitive and looks at smaller pieces — single nucleotides, rather than segments of them — making it more precise. Instead of merely identifying two identical samples, this new technique could identify even very distant family members. By 2018, detectives had begun using IGG.

However, IGG depends on genetic databases owned by private companies rather than ones operated by governments. A DNA profile is only entered into CODIS if someone has been arrested or charged with a crime, whereas IGG uses voluntarily provided DNA profiles, usually obtained through consumers’ DNA testing. Under certain circumstances, law enforcement can access these profiles. The companies operate independently, and regulation of how they use their data is minimal. Often, any oversight relies on terms of service that the companies themselves control.

The partnership between private DNA databases and law enforcement has become extraordinarily powerful. Perhaps IGG’s most famous proof of concept was the so-called Golden State Killer, who terrorized California during the ’70s and ’80s, committing numerous home invasions, rapes and murders. By 2001, DNA evidence had proved that a single man was responsible, but investigators were unable to find a match using CODIS.

IGG depends on genetic databases owned by private companies rather than ones operated by governments.

In 2017, detectives tried again. They uploaded the DNA profile into GEDmatch and MyHeritage, companies where people researching their family history can compare their DNA profiles with those of other users.

Once an individual opts into data sharing, their DNA profile is accessible to other GEDmatch users, much like a social media profile. Once uploaded, it returns a list of any relatives who have uploaded their DNA to the same database.

That’s how the Golden State Killer was caught: One of his distant relatives had uploaded their DNA to MyHeritage. The DNA matched with one of the crime scene samples, and the killer eventually pleaded guilty to 13 murders, as well as crimes against more than 60 people. The case showed just how effective IGG could be — especially for long-unsolved crimes.

IN JULY 1980, just outside Bakersfield, California, the body of a woman who had been stabbed 27 times was found dumped in an almond orchard. She carried no identification, and Kern County detectives could not match her fingerprints with anyone, though they thought she might be Native American. The autopsy showed she had previously given birth and that she’d been sexually assaulted before her death. She had two tattoos: a rose surrounded by the words “Mother I love you,” and a heart with the words “Seattle” and “Shirley.”

In Canada, Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to experience violence than non-Indigenous women.

This particular “Jane Doe” was part of a horrific pattern: Throughout North America, Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit, trans and queer people are being murdered and disappearing altogether. According to a 2016 study funded by the National Institute of Justice, four in five American Indian and Alaska Native women in the U.S. have experienced violence. In Canada, Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to experience violence than non-Indigenous women.

Canada held a three-year federally mandated investigation, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). The final report, from 2019, acknowledged that “there is not an empirically reliable estimate of the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada” but concluded that it constituted a “genocide”. Advocates estimate that the number of cases is on the order of 4,000; meanwhile, a count in 2014 by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) — one of Canada’s largest policing agencies — tallied only 1,181 cases during a 32-year span.

Even with the RCMP’s lower estimate, Indigenous people account for 25% of Canada’s homicide victims between 2015-2020, despite comprising only about 5% of the country’s population. These statistics, already a decade old, appear to be the most recent of their kind reported by RCMP.

The National Inquiry was clear about the root causes of the epidemic: colonial structures, including the Indian Act; the removal of Indigenous children from their homes; forced attendance at residential schools and breaches of Indigenous rights, all of which directly resulted in increased rates of violence, death and suicide in Indigenous communities.

Of the 1,181 cases that the RCMP acknowledged, 225 remained unsolved as of 2013. For family members, the response is slow and disappointing. In Canada, 91% of homicides involving non-Indigenous women are likely to be solved, compared to just 77% for Indigenous women. The crisis is similar in the U.S. According to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center, more than 5,700 American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls were reported missing in 2016, and advocates believe the number could be even higher, given that authorities sometimes think victims are Latina or white.

A 2008 study funded by the U.S. Department of Justice found that women on some reservations are killed at a rate more than 10 times the national average. The U.S Department of the Interior told HCN that they did not have any additional information about the percentage of cases solved relating to Indigenous women and girls.

A 2008 study funded by the U.S. Department of Justice found that women on some reservations are killed at a rate more than 10 times the national average.

In response to families’ demand for justice and attention to the crisis, Canada and the U.S. have developed initiatives both within and across their own borders. In the U.S. in 2021, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) announced the creation of the Missing and Murdered Unit (MMU) inside the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services to address MMIWG cases and strengthen law enforcement’s resources. According to the Department of the Interior, the initiative’s funding level has grown from $5.5 million to $16.5 million over fiscal year 2020 through 2022. The fiscal year 2023 Omnibus Appropriations bill maintained Bureau of Indian Affairs MMIP funding at $16.5 million.

In Canada, the response to MMIWG cases has been fragmented. The Tyeereported in 2021 that the RCMP, Canada’s national police force, lacked a coordinated strategy, while the regular police force does not separately track MMIWG cases. A few months later, Canada launched a national action plan to address MMIWG cases.

Throughout North America, families have waited decades for information. “Every family that we heard from was waiting, waiting for an answer,” said Marion Buller, who is Cree and a member of Mistawasis First Nation as well as the chief commissioner of Canada’s National Inquiry. “They were prepared for bad news and good news.

“A loved one was murdered or went missing 20, 30 or 40 years ago, and they were still waiting for something,” she continued. “They have not given up hope.”

According to Buller, people are not generally concerned with issues of privacy when they have been waiting so long; at this point, they’re simply desperate to find their loved ones. “Some families would very willingly provide samples of their own DNA if that would somehow identify a lost loved one’s remains or provide a lead to locating their lost loved one,” Buller said, adding that she had heard from families who had made this offer to law enforcement and been turned down.

“Every family that we heard from was waiting, waiting for an answer.”

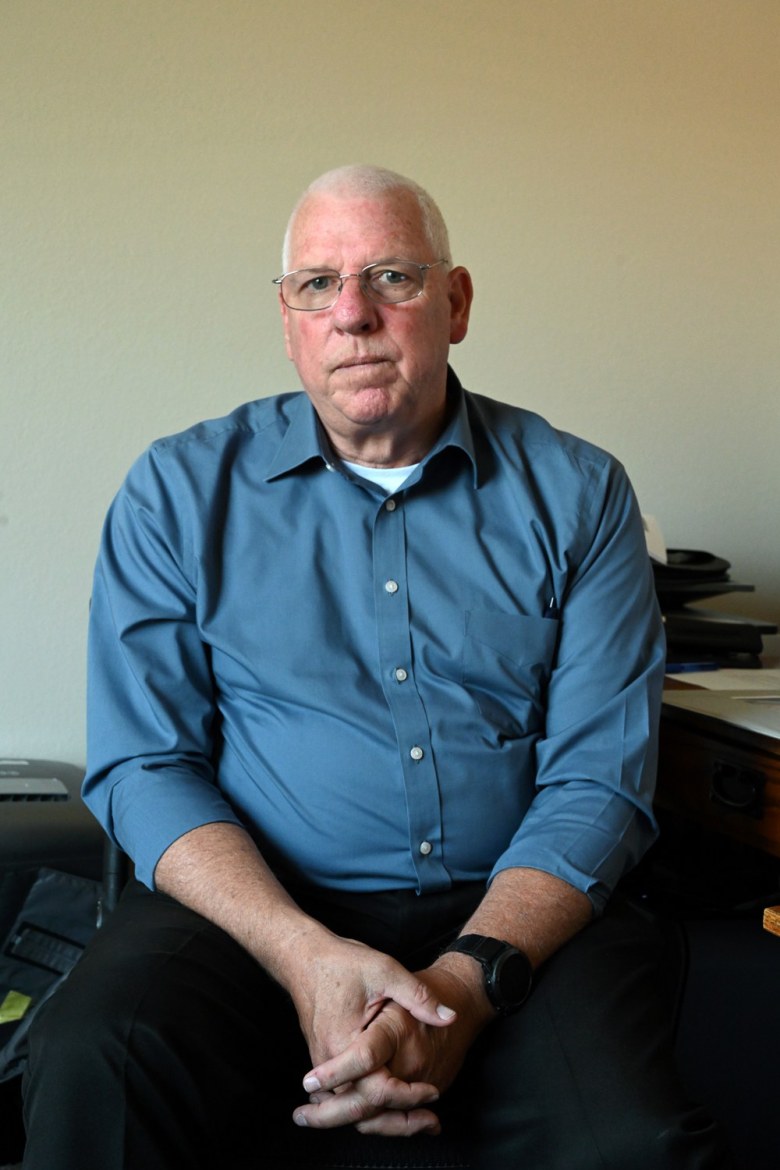

STEVE RHODS, a retired detective who previously worked as a cold case investigator for the Ventura County District Attorney’s Office, cruised down a highway in California in August 2022, heading toward the scene of a cold case he had been assigned to a decade earlier.

He pulled off the highway near Bakersfield, a city in Kern County known for its oil and agriculture, and parked at an intersection surrounded by almond orchards. He thumbed through a binder until he found a police report from 1980 that described the crime scene.

After counting the rows of trees in the orchard, Rhods strode it quickly, almond shells and leaves crunching underfoot. He stopped at a patch of green grass.

A woman had been found in the orchard on July 15, 1980, along with a cigarette pack and beer bottle, but law enforcement could not identify her.

In 2007, Kern County reopened the orchard case. They ran DNA belonging to the suspect through CODIS and identified a man named Wilson Chouest.

In 2012, Detective Rhods was assigned to another cold case with DNA evidence that also matched Chouest. At that point, Rhodes’ team asked to join the two cases together.

Detectives interviewed Chouest, and he admitted to crimes, including robbery and rape, but denied murdering anyone. (Chouest was convicted for the murders in 2018.) But the woman in the orchard remained unidentified.

In 2018, Rhods had an idea: As one of the detectives who helped identify the Golden State Killer, he knew how powerful IGG could be. On his advice, Kern County sent DNA from the woman in the orchard to the DNA Doe Project, a nonprofit that uses IGG and GEDmatch to identify the bodies of unknown people.

Carl Koppelman, a volunteer investigator with the DNA Doe Project, began working with the group in 2018. At the time, he was an amateur websleuth with a talent for solving cold cases and creating lifelike John and Jane Doe portraits. Now, he also uses IGG.

When someone uploads an unidentified DNA profile from a crime scene, GEDmatch automatically creates a list of people who are related to that person. For each individual, there is a number called a “centimorgan” — a measurement of how much DNA every relative shares with the unidentified person. It’s measured on a scale of zero to 3,600, with “zero” meaning they are not related, while around 3,600 indicates a parent-child relationship.

Using that data, along with the email address and name associated with the DNA profile, and other public information — including social media profiles or birth certificates — a sleuth can build a family tree for the unknown person and, eventually, identify them.

If a close relative is located, the Doe Project calls the detective on the case, who then contacts that relative to ask if they have missing family members and to request a DNA sample that could lead to an identification.

To build Shirley Soosay’s family tree, DNA Doe Project investigators entered her DNA into GEDmatch and built her family tree until they were able to identify relatives from several geographic regions —Montana, Manitoba, Canada, and Maskwacis in Alberta. Her closest relative was a band member near Maskwacis.

The DNA Doe Project posted on Facebook that they were looking for the family of an Indigenous Jane Doe, and that she was likely from near Maskwacis, Alberta. They included a lifelike rendering that Koppelman created using autopsy photos.

And then they waited.

IGG ISN’T THE ONLY NEW DNA tool being used by law enforcement, but it is the most popular. In Canada, the RCMP’s National Forensic Laboratory Services has approved methods such as phenotyping, which can predict someone’s physical appearance — their hair, eye or skin color — using their DNA, and create a snapshot or a composite sketch that can help generate leads in criminal investigations.

Other methods include familial searching, which allows investigators to search the law enforcement databases of a suspect’s family members whose DNA profiles have been catalogued, rootless hair technology — which enables more hair samples to be tested than ever before — and STRmix, a genotyping software used by at least 79 U.S. organizations, including the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, and numerous state and city forensic labs, to analyse DNA previously considered too complex or degraded to use.

But IGG outshines them all.

Verogen is a San Diego, California-based company that develops instruments, software and other products to help crime labs and law enforcement agencies identify people using forensic genomics. Its clients include the U.S. Department of Defense and FBI.

In 2019, Verogen acquired GEDmatch, which now has around 2 million profiles. In 2022, Verogen announced a partnership with the commercial genetic testing company Gene by Gene, “to accelerate the adoption of forensic investigative genetic genealogy.” Gene by Gene, which owns an even larger consumer database, FamilyTreeDNA, offers forensic lab services to law enforcement agencies.

Brett Williams, Verogen’s CEO, said over 500 cases in the U.S. have been solved using IGG.

According to Williams, Verogen’s services provide an opportunity to solve cold cases. Williams estimated there is a backlog of 1.1 million unsolved violent crime cases in the U.S. that would benefit from the use of IGG, and about 58,000 cases are added each year. But IGG is only used in 2% of cases, he said, probably because most forensic DNA labs in the U.S. are publicly funded and often lack the necessary funding and technology.

He said that providing tools to public labs will “democratize” the process of solving cases. “When you democratize the technology, you make it available for every person (or) lab that actually wants to do the work.”

Williams sees a market for making genetic genealogy easier to do. Building family trees can require both time and expertise, but Williams said his company is training algorithms that might eventually make the process more efficient. He knows that family mapping can be complicated — mistaken paternity, for example. “It’s a tough project, but I think it’s a problem that can be solved.”

The more people who upload their DNA profiles to databases, the more powerful IGG becomes, he said.

A 2018 study found that if a database like GEDmatch reached 2% of adults with European descent in the U.S., more than 99% of people in that population will be identifiable through family mapping and publicly available information. The geneticist who led the study told Science magazine, “In a few years, it’s really going to be everyone.”

Once a DNA database contains 1% to 2% of a population, the data becomes so granular that IGG can be used to identify most people in that population — even if 99% of them did not spit in a tube and create a DNA profile.

Americans of Northern European descent make up most of the profiles in GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA, but as the company expands into more countries, Williams hopes that people around the world will create profiles.

“If you can get 1% to 2% of the Indigenous population in a database, you could solve up to 90% of cases.”

Williams said he doesn’t know how many Indigenous people have profiles in GEDmatch. But he said that if more Indigenous people create profiles, it will increase the potential to solve missing and murdered Indigenous people’s cases.

“If you can get 1% to 2% of the Indigenous population in a database,” he told HCN, “you could solve up to 90% of cases.”

But experts warn that increasing the number of Indigenous profiles in databases like Verogen’s could endanger Native peoples in other, unforeseen ways.

Jessica Kolopenuk (Cree from Peguis First Nation), who is an assistant professor and research chair of Indigenous health at the University of Alberta’s medical school, researches genomic policy and Indigeneity. In an email to HCN, Kolopenuk wrote that while new technologies propose partial solutions, they “could, under certain circumstances lead to further colonial harm. This is why the question of control and governance of data is so important.” Kolopenuk also questions who should be governing such sensitive and personal data, not to mention existing concerns over possible data leaks and hacks.

Joseph Yracheta (P’urhépecha), who runs the Native BioData Consortium in South Dakota, said that databases like GEDmatch pose a risk to Indigenous people because they can be “another round of extraction” akin to taking someone’s property without permission.

“Even with the basic functionality of having the DNA and a place to match that DNA to go look for a killer, it’s likely not to work the way that it was intended because of the structural elements of racism and government relations with tribal people,” he said.

The justice system disproportionately incarcerates Indigenous, Hispanic and Black people, Yracheta warned, adding that existing inequities are likely to become even more entrenched.

“The system is just not trustworthy for us.”

IN 2020, after nearly 40 years of searching for her aunt, Violet Soosay made an announcement at a women’s conference in Calgary. “I said, ‘I’m getting old, and because I made the promise, one of my kids is going to have to take over and look for her.’” And then, just days later, she saw the DNA Doe Project’s Facebook post. “That’s her, this is my aunt,” she thought.

“That’s her, this is my aunt.”

Soosay, whose DNA profile was already on Ancestry, contacted the sheriff’s office, the coroner and the DNA Doe Project. The DNA Doe Project set up a meeting so they could guide her in uploading her DNA to GEDmatch. Soosay believed it would be a match — and it was.

“I was elated, I was sad, I was angry, I was relieved,” she said. “All these different emotions came all at once. I cried, I laughed. It was an insane moment.”

In 2022, Shirley Soosay’s remains were finally returned to Maskwacis, and she was laid to rest with a ceremony in a community cemetery. Her niece never thought about what might happen to her data, or to her aunt’s — not until years later.

GEDmatch has had at least two privacy breaches since Violet Soosay uploaded her DNA data. In July 2020, its database was hacked and all the user permissions were reset, exposing all 1.45 million profiles on the site for several hours. Kits that had been marked “private” or “research”, meaning they were not supposed to appear in match lists, were opted into law enforcement sharing.

Later, in 2023, following reporting by The Intercept, the DNA Doe Project admitted that from 2019 to 2021, its leadership and volunteers exploited a GEDmatch loophole that allowed them to access the DNA profiles of people who had opted out of law enforcement use. DNA Doe Project founder Margaret Press acknowledged in a statement that she discouraged her team from reporting the loophole to GEDmatch. “Our actions reflected our organization’s culture at the time. We had been working in the wild west with no rules other than our own sense of justice.” Verogen said that it fixed the loopholes.

The nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is one group advocating for regulations. Jennifer Lynch, general counsel and former surveillance litigation director with EFF, told HCN that users should be able to count on some privacy when it comes to their personal DNA data, even if other people can access it. Genetic data can reveal extremely sensitive information.

According to Williams, Verogen’s CEO, GEDmatch does not supply much information to law enforcement. He emphasized that the only profiles the company can see are those of users who have agreed to share their information with law enforcement, and the only clues to identity seen in a profile are the customer’s username and email address.

But Lynch argues that genetic profiling techniques like IGG are so advanced that if just one person willingly adds their DNA profile to a database and allows law enforcement to use it, that person’s data can reveal information about family members who never consented to share that information.

This data is so sensitive that Lynch believes it should be protected by the Fourth Amendment, which guards against unreasonable search and seizure. In 2018, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court set a precedent that, under the Fourth Amendment, there is an expectation of privacy when it comes to information that is very revealing, such as cellular location data.

IGG can be used to identify people in all sorts of criminal cases because there are few legal guardrails, Lynch said. In 2021, Montana and Maryland became the first states to pass legislation limiting law enforcement’s use of IGG. Some states have passed varying genetic data privacy laws that may or may not apply to IGG, but most states still don’t have any regulation.

The U.S. Department of Justice and Ventura County, where Rhods was a detective, have created their own policies. But without laws governing the companies’ actions, the companies can change the rules to suit their needs. GEDmatch’s rules, for example, have changed over time.

Before Verogen acquired GEDmatch, the database said that law enforcement could use the DNA profiles to solve violent crimes, which it defined as homicides and sexual assaults. GEDMatch has since broadened its definition of violent crime to include nonnegligent manslaughter, aggravated rape, robbery and aggravated assault. FamilyTreeDNA has its own definition: homicide, sexual assault or child abduction.

Neither database allows law enforcement to use IGG to solve cases involving stalking, however. But Lynch cited a case in which police used it for that purpose. In 2022, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California announced that it had successfully prosecuted a man who stalked actress Eva LaRue and threatened to rape LaRue and her daughter. The FBI, which investigated the case, did not publicize which database it used.

This data is so sensitive that Lynch believes it should be protected by the Fourth Amendment, which guards against unreasonable search and seizure.

“If these companies are willing to allow law enforcement on an ad hoc basis to just access the data, I don’t think that you can ever trust there will be true restrictions on access,” Lynch said.

GEDmatch and FTDNA’s databases are commonly used by law enforcement. In the stalking case, Williams said, Verogen was “not approached by the FBI regarding this case.” A press officer for Verogen added that the FBI may have approached GEDmatch before Verogen acquired it in 2019. If the company was served a warrant, Williams said, “We would push back on that, probably. If it’s against our terms of service, we would have to have a conversation with them about that.”

Williams believes that Verogen’s users limit what it can do. If the company changes its rules arbitrarily, Williams said he is “absolutely certain” that its users will delete their profiles.

Lynch, however, warned that without regulations, IGG could someday be used to surveil political protesters, potentially violating their First Amendment rights.

Law enforcement has often cast environmental demonstrators as threats to public safety. Protesters have faced charges for serious crimes, including domestic terrorism, for blocking construction of pipelines and other infrastructure.

Protesters do have the legal right to conceal their faces, Lynch said. But since everyone sheds DNA wherever they go, it’s possible for law enforcement to collect protesters’ DNA and use IGG to identify them. This means that the very same DNA that families like Violet Soosay’s shared to find lost relatives might someday be used to identify other relatives, including people who are fighting for Indigenous rights. Lynch pointed to a 2019 case in which police used CODIS to search for DNA from a cigarette butt to identify a Lakota man they accused of protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline. The charges against the man were later dropped.

“If these companies are willing to allow law enforcement on an ad hoc basis to just access the data, I don’t think that you can ever trust there will be true restrictions on access.”

Williams said that identifying political protesters is not a legitimate use of IGG and that it is not allowed under GEDmatch’s terms of service.

Ventura County and the Justice Department have policies regarding their use of IGG. Both allow law enforcement to covertly collect DNA without consent under certain circumstances. The Justice Department’s policy allows law enforcement to use IGG to solve a wide variety of crimes, including attempts to commit violent crimes, with a prosecutor’s permission, when there is a threat to national security or public safety.

Law enforcement can access DNA profiles in GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA with a warrant or subpoena. But Williams said that, since Verogen acquired GEDmatch, it had only submitted to police warrants for cases that fell under its definition of violent crime.

According to Lynch, the only way to guarantee that law enforcement won’t eventually use IGG to solve minor crimes is to regulate the practice. “We need to pass laws at the state and federal level that very clearly lay out when law enforcement can use this technique and require judicial authorization, and there need to be consequences for violating those laws.”

CHIEF VERNON SADDLEBACK is the leader of the Samson Cree Nation, home to the Soosay family. He is aware of Shirley Soosay’s case and of Violet Soosay’s long journey for answers. Chief Saddleback told HCN that his community has yet to have a serious discussion of DNA analysis and Indigenous sovereignty, though he strongly believes it is a worthy topic. He added that Indigenous communities should proceed with caution, even though IGG offers the opportunity to locate long-lost relatives.

“There are good intentions … and I can see why they do it,” Saddleback said. “But then you have to ask yourself that question: Is someone going to use this (DNA) for ill will? That’s where I struggle.”

Saddleback believes that transparency is essential; anyone who submits DNA for any purpose should be clearly informed about exactly what they are giving away, so that they can make a more conscious decision. For Indigenous communities, this is both personal and cultural: Giving away your own DNA also means exposing the genetic makeup of other people and the community itself.

“I want all my people taken care of,” Saddleback said. “But at the same time, how do I protect Violet’s DNA now?”

Several Indigenous-led genetic institutions have emerged in countries around the world, dedicated to this work. They are leading serious conversations about privacy and strengthening Indigenous data sovereignty to ensure that genetics research is controlled by and benefits Indigenous people.

“You have to ask yourself that question: Is someone going to use this (DNA) for ill will? That’s where I struggle.”

These institutions are erecting a crucial barrier against the colonial and genocidal strategies and policies that have been upon Indigenous peoples for centuries — poverty, the dispossession of land, prohibition of healing practices, unethical medical experiments and inadequate access to health care.

In Canada, the Northern Biobank Initiative at the University of British Columbia is the first biobank project in British Columbia focused on disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment for the province’s northern population. The biobank holds blood and tissue samples to improve the understanding of Indigenous patients.

In Australia, the National Centre for Indigenous Genomics, which is dedicated to biomedical research that benefits Indigenous people in Australia, has become a safe, permanent place for the biological samples and genomic data of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

And in the U.S., Joseph Yracheta’s Native BioData Consortium in South Dakota is another growing research institute led by Indigenous science, bioethics, data and policy experts. Launched in 2018, the nonprofit biobank is dedicated to Indigenous health, genomic and data sovereignty.

Joseph Yracheta, the executive director and lab manager, said the consortium’s work is crucial to safeguarding participants’ samples from exploitation. Its doors are open to any tribe or Indigenous group in the world that wants to store data, with all decisions made by individual tribes.

“We will make sure that tribal leaders and government know that the samples are there,” Yracheta said. “We will continually ask them, ‘Do you want them destroyed, do you want them used, do you want them returned to you?’”

“We will make sure that tribal leaders and government know that the samples are there.”

Yracheta said there’s good reason to be sceptical of non-Indigenous groups storing Indigenous DNA. In 2002, the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) First Nations leaders demanded the return of blood samples that were donated for an arthritis study in the 1980s, but later used without permission for numerous other studies. In 2004, the Havasupai Tribe sued the Arizona Board of Regents and an Arizona State University researcher after learning that DNA samples donated for genetic studies of Type 2 diabetes were used without permission for other genetic studies that looked at inbreeding, schizophrenia and the tribe’s origins.

Carletta Tilousi, a former Havasupai councilwoman, said that scientists approached her when she was 19 to ask if they could take her blood in order to find out whether she was susceptible to having diabetes. Tilousi, who does not recall signing a consent form, never heard back from them, but later found out that her blood sample was being used in a different study at ASU. In 2010, an investigation found that about 100 tribal members signed a consent document, and most had not completed high school, and English was their second language. “It really just felt like somebody really kicked you in the stomach,” Tilousi said. She saw people crying as they heard the report’s findings. Tilousi, however, didn’t cry because she was in shock. And the more she thought about it, the angrier she felt.

After six years of litigation, the case reached a settlement that included the return of blood samples to the tribe. In the end, she felt that justice was served through the lawsuit and returning of the blood samples. “For me, our bodies are sacred,” Tilousi said. She believes informed consent must be guaranteed, with a full explanation of what will be done with any samples. “They have to be provided translators, they have to be provided an explanation on what’s happening to their bodies, what they’re doing to our bodies. That’s what’s most important is the respect given to us Indigenous people, because the way we treat our bodies is differently from the way most societies do.”

VIOLET SOOSAY HAD NO WAY way of knowing that she had uploaded her DNA to GEDmatch at a time when its terms of service were in flux.

By spring 2018, law enforcement had used GEDmatch to solve cases. But in April 2018, when law enforcement officials announced that they had arrested the Golden State Killer with the help of GEDmatch, a backlash arose from privacy advocates.

In May 2018, GEDmatch formally changed its terms of service to allow law enforcement to use GEDmatch to solve violent crimes, such as homicides and sexual assaults, and to identify human remains. In May 2019, GEDmatch changed its terms to opt all users out of sharing information with law enforcement, unless they opted in. In December 2019, Verogen acquired GEDmatch.

By early 2020, when Soosay worked with the DNA Doe Project, Verogen was the new owner of GEDmatch.

In order for the Doe Project to compare her DNA to Shirley’s, Violet had to click an opt-in button that made her sample public to the full database. She had the option to click an opt-out, but this would have prevented her sample from being compared to those uploaded by law enforcement — including Shirley’s.

But Soosay said she was not aware that her data was available for matching in other cases. When she met with the DNA Doe Project years ago, all she remembers is her desperation to find her aunt, and her hope that this process would help bring closure. After 39 years of searching in vain, she said, she was “grasping at straws.”

The people she spoke to told her to upload her DNA to GEDmatch, she said. But she doesn’t remember if they explained what would happen to her data, though she said she may have clicked a button on a consent form.

Pam Lauritzen, spokesperson for the DNA Doe Project, wrote in an email to HCN that there was no recording of the call with Soosay, but that she had had to allow law enforcement matching in order for her DNA profile to be compared with her aunt’s. “Profiles that don’t allow law enforcement matching are not available to organisations like ours that are working on cases of unidentified remains.”

When HCN told Soosay that her DNA profile may have been available for law enforcement to use in other cases, it was the first time she realised her data could be used for other purposes.

“Now I’m concerned,” she said. “Now you’ve opened a can of worms that I wasn’t aware of.

“I feel violated. I feel there’s no respect for my person, there’s no respect for my people, the bloodline that I come from, or the clan that I belong to.”

Lauritzen said that people who want to help the Doe Project identify human remains still must allow their data to be accessed for use in other cases on GEDmatch: “This would allow matching to our cases as well as cases uploaded by other agencies and organisations working on forensic cases. Of course, users of GEDmatch have the option to change their preferences or even delete their profiles.” Lauritzen said they recommend carefully reading the terms of service before uploading to GEDmatch.

Brett Williams, Verogen’s CEO, is aware that some groups are hesitant to make profiles on GEDmatch. He said they are working on a solution that would allow them to upload DNA profiles into a database that they can control. And he says he is in favor of regulating genetic genealogy and preventing its use for surveillance.

Williams said that Verogen lacks a policy for respecting Indigenous sovereignty and that there is no one on staff who is responsible for DNA sovereignty.

When HCN first spoke to Detective Rhods in 2022, he was against regulating IGG. He believed that the guidelines developed by the DOJ and Ventura County amounted to a good middle ground between regulations and a free-for-all. But after HCN shared its findings about privacy and potential harms, Rhods shifted his stance. He said he supported regulating IGG so that it can only be used to solve violent crimes, such as rape, murder and kidnapping.

“If we’re going to pass a law — and clearly, someone’s going to want a law — then let’s mirror the policy, let’s just codify the policy into law,” he said, referring to Ventura County and the Justice Department’s policies.

Rhods had not previously considered that Indigenous people might have unique concerns about DNA. “All I’m concerned about is identifying the victim or suspect, and I don’t think about these global ramifications,” he said.

When Rhods was working a case and wanted to convince people to supply their DNA to solve a cold case using GEDmatch, he offered them a free commercial DNA test kit and explained that he needed their DNA to solve the case.

He then uploaded their DNA data to GEDmatch. He created a user account that only he had access to, which means that he was the one who checked the boxes opting in and out of different privacy settings. After a case is solved, he said, he removed the person’s data or turns the account over to them. But until then, it’s public. He followed the Ventura County and Department of Justice guidelines for using IGG, he said, and also deploys his own “spin.” He calls GEDmatch “the Facebook of genealogy” to remind people that profiles are publicly accessible.

Rhods said he tried to respect the privacy of people who shared their DNA data with him. But he didn’t read them the GEDmatch terms of service “because that’s just a bunch of lawyer-speak.” It was, he said, the user’s responsibility to read the terms.

Rhods said he didn’t tell people that their DNA could be used by law enforcement to solve other cases. “I don’t think I’ve ever explained it to a person that way,” he said.

Violet Soosay said she isn’t opposed to her data being used to solve other cases, but adds that someone should have asked her permission first. She believes that there need to be laws governing IGG, though. She worries that Indigenous DNA might be used by non-Indigenous groups in ways that conflict with Indigenous worldviews, and said she agreed with Yracheta that Indigenous people should govern their own data and develop consent protocols.

“All of this information should have been relayed to people like me who are uploading their DNA,” Soosay said.

She knows that having her data out there might help other people. “But I know how the settler societies think, which is totally different from mine,” she said. “It’ll be utilized for something other than for the good and the benefit of others.

“I went into this wanting to solve my auntie’s missing file,” Soosay said, “and I never intended for anything other than that.”

This project is supported by the Global Reporting Centre and the Citizens through the Tiny Foundation Fellowships for Investigative Journalism.

Hilary Beaumont is a freelance investigative journalist, covering climate change, Indigenous rights and immigration. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram: @hilarybeaumont.

Martha Troian is an independent investigative journalist and writer. She has covered everything from Indigenous politics, human rights, missing and murdered Indigenous people, to environmental issues. Follow her on Twitter @ozhibiiige.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.