When the simple blue-and-white postcard arrived in January 2023, Sarah Ferris missed it. The mailer, sent by the city of Vancouver, Washington, told 270,000 municipal water users that a group of chemicals called PFAS had been found in city water. Levels were low, the postcard said; the city would soon test again to comply with state law and share more information.

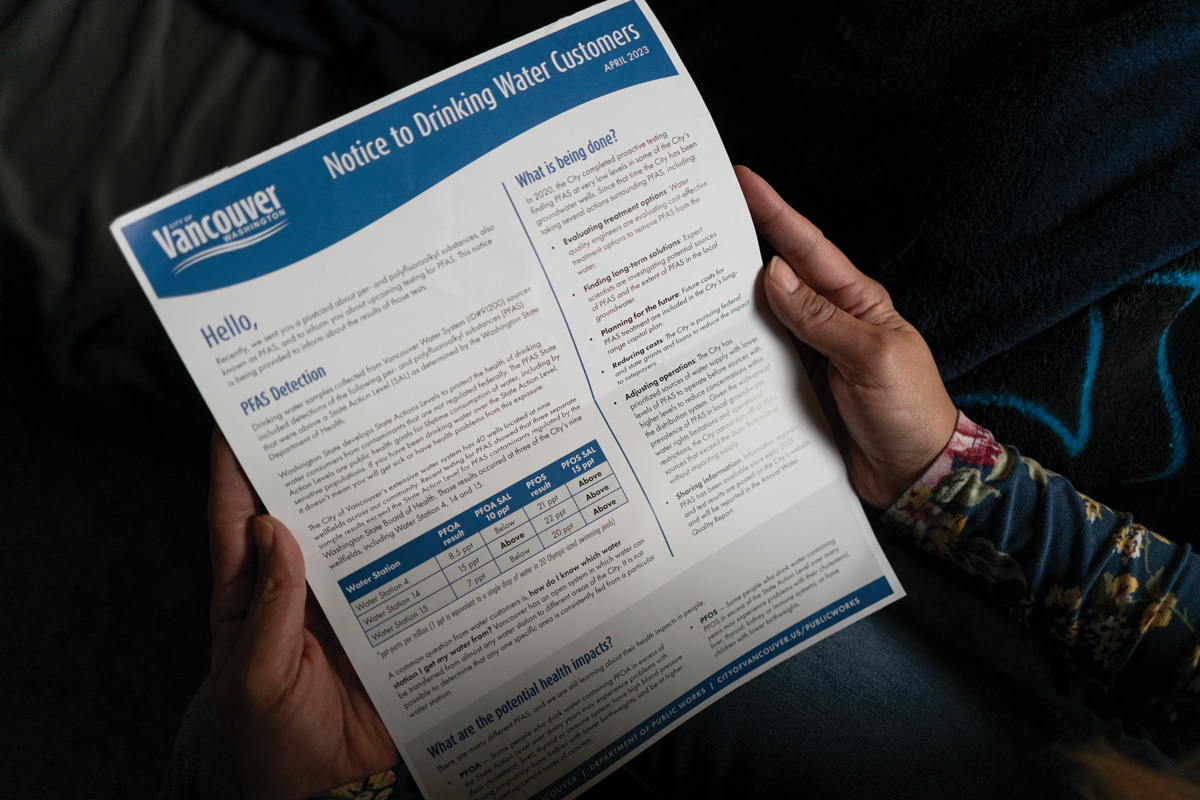

When a more detailed flyer arrived in April, Ferris looked it over. A chart showed that water at three of the city’s nine wellfields had tested above the state limit for two common PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS. Other sections called these levels “very low,” and said experts were “still learning about their health impacts.”

Ferris tried to decipher it all. “I was scanning, not really having time to delve into all of it and decode,” she recalled. She was busy, six months pregnant, finally over the first-trimester nausea but anxious about her high-risk pregnancy. There was also a new part-time job and an impending breakup that would soon make her a single mom. Ferris dropped the flyer onto a stack of papers to read later, but never did.

She knew nothing then about PFAS, which have been linked with both preterm birth and low birthweight, along with preeclampsia, birth defects and developmental delays. She didn’t know that as a pregnant person, she and her baby were among those at highest risk from these chemicals. PFAS, frequently called “forever chemicals,” can accumulate in the body — even faster in a baby’s — and persist for years.

Even if she had studied the flyer, she might not have fully understood the risks. Key details were missing, including that three more wellfields had tested nearly as high, putting half the city’s water supply near or over the state limit. It downplayed overwhelming evidence of the health risks and failed to mention that the Environmental Protection Agency’s latest guidance is that no amount of PFAS in drinking water is safe.

“We want to be as transparent as possible with this,” said Tyler Clary, Vancouver’s water engineering manager, who helped shape the city’s PFAS communications. “We don’t want a negative headline.”

But by trying to minimize public alarm, officials here — and all over the U.S. — have fallen into a pattern of communication missteps, experts say. Even well-meaning officials often provide inadequate or misleading information, putting communities at higher risk.

Researchers estimate at least two-thirds of all U.S. residents’ water is contaminated by PFAS. That number will likely grow as the EPA tests more water systems. In contaminated communities, “it’s very important to acknowledge that a terrible thing has happened,” said Alan Ducatman, a professor emeritus at West Virginia University. “That’s the opposite of what so many communications do. They just dismiss the problem.”

PFAS — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — have been in the public eye since the early 2000s, after a series of lawsuits revealed that PFOA pollution from a West Virginia chemical plant was killing animals and people. Unlike contaminants like lead, PFAS aren’t a single chemical, but a class of more than 9,000, each designed to be nearly indestructible. They’re ubiquitous, used in cookware, pizza boxes, carpeting and other products to make them waterproof, nonstick or stain-resistant. They leach into groundwater near chemical plants, factories, military bases that used PFAS-containing firefighting foam — even septic systems, where particles in water and waste accumulate.

PFAS are also tiny: Their contamination is measured in parts per trillion (ppt) — the equivalent of a single drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools. That comparison frustrates some communications experts, who say that when something is described as that small, it’s easy to dismiss, even though PFAS’ health effects at low levels are well documented.

Researchers estimate at least two-thirds of all U.S. residents’ water is contaminated by PFAS. That number will likely grow as the EPA tests more water systems.

Those effects aren’t easy to explain, either: Different PFAS affect many systems in the body, but over long time periods. Thousands of studies have concluded that various PFAS increase the risk of myriad conditions including high cholesterol, kidney cancer and liver disorders. But it’s not easy to attribute these diagnoses to any one thing, making it hard for individuals to connect the dots.

Chemical giants DuPont and 3M had long known about the health dangers of PFOA and PFOS, but it took federal regulators decades to catch up. Because the EPA was slow to set rules, some states, including Washington, set their own — but these vary widely. The EPA’s most recent guidance offers welcome clarity, experts say: The ideal goal is zero. But zero isn’t realistic, so the agency proposed a limit that current tests can reliably measure: 4 ppt for PFOA and PFOS. That rule, proposed in 2023, has not been finalized; when it is, it won’t take effect for three years.

The proposed rule, plus an uptick in lawsuits against chemical companies, has thrust PFAS back into headlines. But they’re still not a household name. “Talking to regular working folks in our community, they don’t know what PFAS are,” said Kim Harless, a Vancouver city councilmember.

Vancouver officials decided to focus on the state limits in public communications — 10 ppt for PFOA, 15 ppt for PFOS — and haven’t included the EPA’s guidance of zero anywhere. Washington’s limits “are the known, those are the required, so that’s what we follow,” said Laura Shepard, city communications director. Focusing on pending rules or unenforceable goals would be confusing, she said: “It starts to get muddy really fast.”

Ducatman, who wrote a 2022 paper analyzing — and criticizing — many agencies’ PFAS communications, disagrees. “I think it’s reasonable to tell the truth: To say, ‘We’re not sure there’s any safe level, and we’re going to go with this standard,’” and then explain why. Suggesting that higher levels are safe, he said, might foster distrust in the long run.

MARIE’S BABY was five months old when she opened the April flyer. A physician assistant as well as a mom, she wanted to understand everything. “I read it a million times,” she said, and then did more research online and in medical journals. (Because her employer hasn’t authorized her to speak on this public health matter, Marie asked to be identified by only part of her name.)

The flyer recommended that people who were pregnant, breastfeeding or mixing formula switch to using safer water, and Marie was relieved that her sink and fridge already had filters. But after reading it, she also assumed that the city’s water was still below a safe threshold, and that scientists weren’t sure of the health impacts. Months later, she was among dozens of women in a Vancouver moms’ Facebook group who replied to an HCN inquiry seeking pregnant and nursing peoples’ experience getting — or not getting — information about PFAS. Sitting on her kitchen floor as her 3-year-old clung to her, Marie and her husband were surprised to learn from HCN that much of the city’s water was near or over state limits, with most of it exceeding both EPA guidance and the proposed rules. They said they would have been even more careful, had they known.

This lack of sufficient information is part of a nationwide pattern. Papers by Ducatman and others, including Whitman College environmental sociologist Alissa Cordner, analyze communications from almost every state’s health or environment agency along with dozens of local and nongovernmental agencies, outlining common failures. Cordner watches for two red flags.

First, she said, officials often emphasize how low levels are, without mentioning that they still carry risk. Vancouver’s flyers and website emphasize the city’s “low” or “very low levels.”

Vancouver’s levels are far lower than some communities: Airway Heights, near an Air Force base in eastern Washington, measured PFOS at 1,200 ppt in 2017, and PFOA at 320 ppt. Most of Vancouver’s wellfields have tested between 5 and 25 ppt. “All we can do is compare ourselves to others,” Clary said.

But being lower by comparison doesn’t mean they’re safe.

“I would not be comfortable saying that 20 ppt is safe,” said Anna Reade, the lead PFAS scientist at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council in San Francisco. Cancer and other risks are elevated at those levels, she said. And children, who consume more water for their weight, face even higher exposures.

Second, officials often claim that health effects are unknown or in doubt. Though Vancouver did list some possible effects, their communications implied a lack of certainty: “Scientists are still studying how long-term exposure to PFAS may affect people’s health,” reads the city website. That’s not wrong, but Cordner and Ducatman say emphasizing uncertainty is misleading.

“You don’t want to exaggerate,” Ducatman said. “But at this point, (we know) it is more likely than not to cause certain outcomes. It’s OK to be transparent about those.”

Asked for comment, Vancouver’s communications team doubled down on the city’s approach. “It’s really irresponsible to communicate about something when it is unknown, when the research is still being done,” Shepard said. She and Clary, who trained in civil engineering, said they relied on state and county health departments for their information; in an interview with HCN, county officials also emphasized the unknowns.

But PFAS researchers say that the evidence pointing to specific health effects is abundant, compelling and consistent. And communications experts say telling people this is reasonable.

“What qualitative studies find is that people want to know. They don’t panic,” Cordner said. “They’re able to take in information and use it to inform decisions for their health and their family’s health.”

By some measures, Vancouver outperformed many agencies. For example, the city translated materials into five locally common languages. And while many agencies emphasize personal responsibility, Vancouver shared what’s being done to address contamination city-wide.

Those steps, however, will take time. Vancouver is designing a filtration system now for one of the smallest, most contaminated sites, but an engineering firm estimated that building facilities to bring PFAS below state limits city-wide would take at least six years and $170 million. The proposed EPA limits would require far more.

Until then, public health communications may determine how people respond — or what they demand from officials. Every expert interviewed for this story said that if they lived in Vancouver, they’d filter their water, especially if they were pregnant or nursing. Councilmember Harless hopes that officials will help low-income households buy filters, but added that further action may depend on public sentiment. PFAS experts hope that greater awareness might also encourage people on private wells — which won’t be addressed by public measures — to test or treat their water.

“What qualitative studies find is that people want to know. They don’t panic. They’re able to take in information and use it to inform decisions for their health and their family’s health.”

FERRIS STILL isn’t sure that she’s protecting her family. She drinks a lot of water to breastfeed, and struggles to find guidance she trusts. Even her doctor couldn’t answer her questions.

The night the flyer came, she’d rushed out and bought a Brita pitcher, using it every day to fill and refill a 40-ounce metal bottle, plus a smaller one for her 7-year-old. She then saw online that Britas don’t reliably filter PFAS, so she started buying bottled water instead — unaware that it’s not tested for PFAS. Finally, she bought a $50 faucet-mounted filter certified to reduce PFAS, which requires a $20 cartridge change every six months — expenses only possible because her ex-partner helped.

Each revelation has eroded her trust in city officials. “It makes me wander a little bit down that trail of, oh my gosh, what about the people that don’t know? And how much don’t I know?”

She still worries.

Sarah Trent is a freelance writer based in southwest Washington. Formerly she was an editorial intern for High Country News. Submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the March 2024 print edition of the magazine with the headline “‘We don’t want a negative headline.’”