After college, I moved back to SOMA, the South of Market district in San Francisco, with no plans except to be home with my mom and Lolo Jesus, my grandfather, while my brother was away finishing college. Lolo’s health declined rapidly; my mom and I would head straight to the hospital after work to be with him. Then I’d spend late nights doing our family’s laundry across the street from our apartment at the Clean Wash Center. My weekly 11 p.m.- 2 a.m. routine at the laundromat provided solace and contemplation. I formed friendships with the elderly Filipino attendants in ways I wished I could have done with my own reticent grandfather, especially after his passing.

Creating the body of work that forms “A Hxstory of Renting” (AHOR) was my way to grieve and honor my shifting world and city. Moving back home after college humbled me. I was confronted with the ironies of tradition and change as a San Francisco third-generation renter.

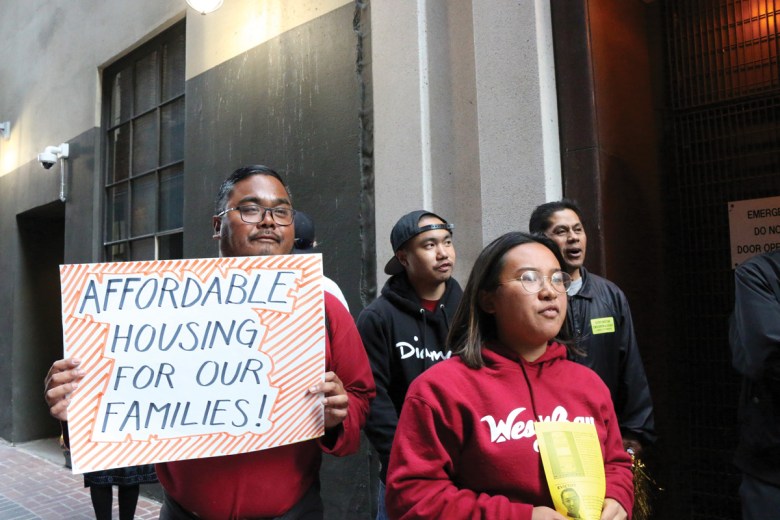

As my 87-year-old maternal grandfather’s health declined after a bad fall, the luxury city buildings rose higher around us, eclipsing the lives of families like mine, who remained vulnerable to the affordable housing crisis. AHOR’s body of work spans photography, archival research, site-specific performance work and installations, poetry, investigative journalism and public activities, such as neighborhood alternative tours and tenant rights workshops.

In one performance, “Scatter Piece,” I routinely strewed poetry addressing the ongoing displacement and gentrification around my working-class neighborhood, Excelsior. This first iteration focused on a contested lot that was supposed to be redeveloped into luxury housing, something the poem addressed through the grief of an eviction and the erasure of a tenant’s history. The poem was translated into languages spoken in Excelsior, including Tagalog, Vietnamese and Spanish, by artists and community organizers — all renters, from Excelsior to Hanoi.

As my 87-year-old grandfather’s health declined, the luxury city buildings rose higher around us, eclipsing the lives of families like mine.

AHOR is my anting-anting, a talisman to combat my city’s complicity and cultural amnesia in gentrification and displacement. But beyond these abstract ideas, AHOR, at its core, is my way of showing my love for my late grandfather.

My family’s hxstory of renting began Dec. 31, 1959, on unceded Bay Miwok Land. That evening, my maternal grandaunt, “Lola” Marina Chioco Peña, began her new life in America as a renter with her husband and five children. She left our ancestral property in Nueva Ecija, Philippines, and compacted her life and dreams within a two-bedroom apartment in the Pittsburg Marina district of Northern California.

As a young person and organizer, my mother traveled between the U.S. and the Philippines from 1983 to 1991. Her work shaped AHOR’s community-engaged framework.

During the 1986 People Power Revolution in Metro Manila, Philippines, my mom carried calamansi-doused handkerchiefs to flush out the tear gas the military threw at demonstrators at Liwasang Bonifacio, the Mendiola Bridge and Welcome Rotonda. She protected ballot boxes before the votes were tallied by sitting on them at voting precincts during the Feb. 7, 1986, Snap Election and the Feb. 2, 1987, Constitution Referendum. While our family’s immigration papers were being processed, my mom, then 16, lived with Lola Marina in Pittsburg, California, getting up at 3 a.m. to walk to McDonald’s for her opening shift.

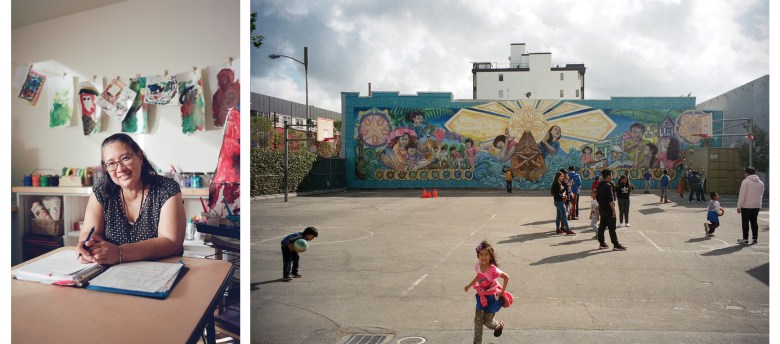

Today, my mom, affectionately known as “Tita Tina,’’ serves the South of Market community as a kindergarten teacher at my own alma mater, Bessie Carmichael Filipino Education Center Pre-K-8. AHOR thrives because of mxntors like my mom, who taught my brother and me to look back to our origins and build the kind of genuine relationships with people that begin when one simply starts showing up.

AHOR accompanies me on my BMW (bus, muni, walking) commute on our local train and bus systems and on my walks, especially along Mission Street, which threads my home districts, rooted in anti-displacement organizing. In its core, Frisco, The City, SCO, Sucka Free, 4-15 — you name it — still remembers who it is, who it was and who it will be through voices like mine that persevere to recollect, contextualize, remember. These are my field notes as an ethnographer on unearthing a facet of my city’s memories: “A Hxstory of Renting.”

Erina Alejo (they/them/siya) is an artist and cultural worker who uses their lens as a third-generation San Francisco tenant in making art that nurtures our narratives, power, and community cultural wealth. We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline A Hxstory of Renting.