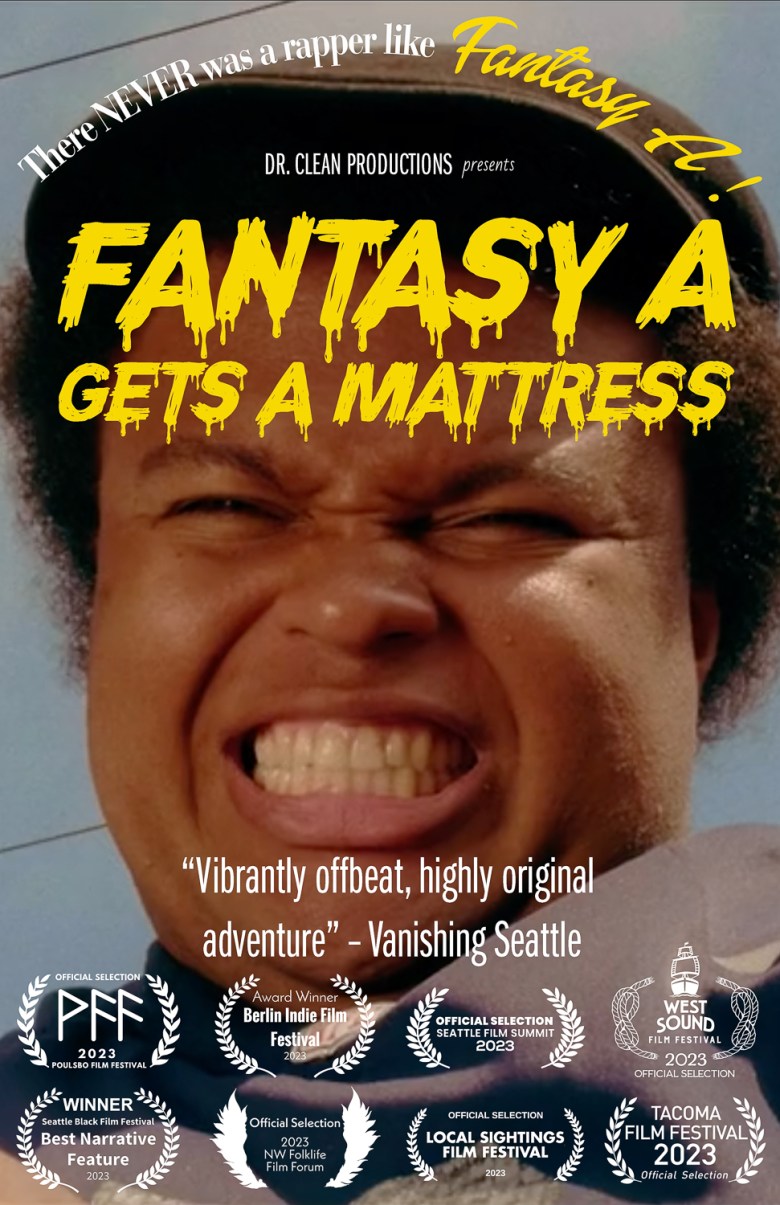

Back in June, a mattress tagged with the words “Fantasy A Gets a Mattress” appeared in front of a small theater in South Seattle, near my house. In the months that followed, I saw the same words throughout the city, spray-painted onto mattresses slumped next to busy roads and tucked away in alleyways. The mattresses were ads — or perhaps fan letters — for Fantasy A Gets a Mattress, a film that the theater has screened 20 times to sold-out crowds.

Fantasy A Gets a Mattress follows Fantasy A (whose legal name is Alexander Hubbard), an autistic Black rapper and writer — and a local legend in Seattle — on a surreal odyssey to find a comfortable place to sleep. It’s a dark, absurd comedy loosely based on the rapper’s own experiences with eviction, homelessness and disability; directors Noah Zoltan Sofian and David Norman Lewis say Fantasy A’s music and writing inspired the film. Those Seattleites who don’t already know Fantasy A likely know of him: His posters have been stapled to nearly every telephone pole in the city.

I saw Fantasy A Gets a Mattress in August and realized why it had packed the room again and again. The film premiered last April, just months after Seattle’s inflation was ranked third-highest in the nation. Any film that asks its audience “How can you make art in a city you can’t afford?” was bound to strike a chord.

Fantasy A both underscores and lampoons the absurd cruelties that artists face, trying to make art while also managing to eat, live, and sleep on a comfortable surface. We learn in the opening sequence that after years of hustling and getting nowhere, Fantasy A thinks he’s found the secret to success: a good night’s sleep on a mattress. His dream, he says in the movie, is to have something normal to sleep on while he dreams.

But when Fantasy A attempts to shoot a music video, he ends up being late for curfew and is kicked out of Gentle House, a satire of a group home for low-income adults with disabilities. In the next profusely sweaty 24 hours, Fantasy A traverses Seattle on foot in quest of a mattress — and his big break.

Fantasy A takes place in summer. The city is hot. Seattle is sun-bleached and vibrant, filled with bright, saturated colors reminiscent of Spike Lee’s earlier films. Like those films, Fantasy A sketches exaggerated portraits of the people in the protagonist’s orbit as the camera follows them around.

Co-director Zoltan Sofian said that the movie references other ’80s movies as well, including the seminal rap documentary Wild Style and Joel Schumacher’s silly D.C. Cab.

And the film is funny. It has hilarious, committed performances from its actors, none of whom had previously acted in a feature film. Fantasy A’s magnetism, in particular, carries the audience through the movie. He delivers gut-busting lines again and again. The actors are why the film is able to tackle heavy topics with humor, wit, and West Coast hip-hop.

But a harsh reality underlies the film’s surreal elements. The characters are clearly meant to represent the struggle working people face in the social and fiscal vacuum created by austerity and neoliberalism: viciously high rents, lack of housing, cruel landlords and, in a running gag, a chronically underfunded transit system.

We meet Fantasy A’s video producer and fellow aspiring artist Asia Rose (Acacia Porter) as she confronts the injustices of the gig economy. She’s a tenant of Seattle Beds, a dingy group home run by Ramon (Logic Amen), a narcissistic property manager with an ego that bruises as easily as an overripe peach. She and the punks in the group home are evicted when Ramon decides to turn Seattle Beds into a dojo, which he dubs the “Ramojo.” At his side is the codependent tenant Zander (Aaron Billingsley), who uses the settlement money he received after being hit by a truck to set up as an amateur loan shark. In the background is Lil Rude Puss (Keosha “Lovely” Fredricks), a semi-famous celebrity who broke out from the Seattle music scene returned to Seattle, her hometown.

The movie cycles through the characters’ lives and perspectives, observing how, as the city wrings them out, they only become more selfish and crueler as they hustle and compete for success. The film successfully exposes one of the most precious things that precarity can rob people of: a sense of solidarity.

Fantasy A pays Asia Rose to shoot a music video, but she abandons the rapper to make her own music instead. She tells him to go try to get work at Scabby’s, a seedy club run by the eponymous booker Scabby. In order to fund his dojo, Ramon vies for Fantasy A’s spot at Scabby’s, although he knows it will crush Fantasy A. He justifies his behavior, saying, “When something bad happens to you, you legally no longer have to be good.”

Despite its almost nonexistent budget, the movie is well-crafted, shot on location in Seattle in places, not all of which will be familiar to Seattleites. Zoltan Sofian said he found many of the locations while riding his bike, working for Postmates. Most of them no longer exist, he said. Some were being torn down during shooting, making the film a “time capsule” of Seattle in the late 2010s. Instead of seeking out popular landmarks or framing expansive blue-green compositions of Puget Sound, the director sought out sets that are pure dust, concrete, rust and graffiti. The interstitial back alleys, dark clubs, industrial zones and skate parks not only serve as low-budget locales, they also expose Seattle’s underbelly, which is rarely captured on film. The movie sends a clear message that this Seattle, the unpretty Seattle, is well worth seeing.

All the while, as the odds continue to stack up against him, Fantasy A stares longingly at the stage at Scabby’s. Who can make art in Seattle anymore? The movie, by its very existence, offers some hope: After more than 20 sold-out showings, it’s clear that audiences are hungry for art from their city.

Fantasy A picked up the Best Narrative Feature award at the Seattle Black Film Festival and has screened at various festivals. The movie will continue screening in Washington in small independent theaters, at the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle, and at the TASH conference in Baltimore.

Natalia Mesa is an editorial intern for High Country News based in Seattle, Washington, covering the Northwest. Email her at natalia.mesa@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.