Journalist Richard Two Bulls, an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota Tribe, was born in Rapid City, South Dakota. He grew up on multiple reservations across the United States, but his extended family lives on Red Shirt Table, a flat-topped mountain on the Pine Ridge Reservation, next to Badlands National Park. His new documentary for South Dakota Public Broadcasting (SDPB), Tatanka: A Way of Life, is an intimate half-hour look at buffalo and the meaning they hold for the reservation and the surrounding area.

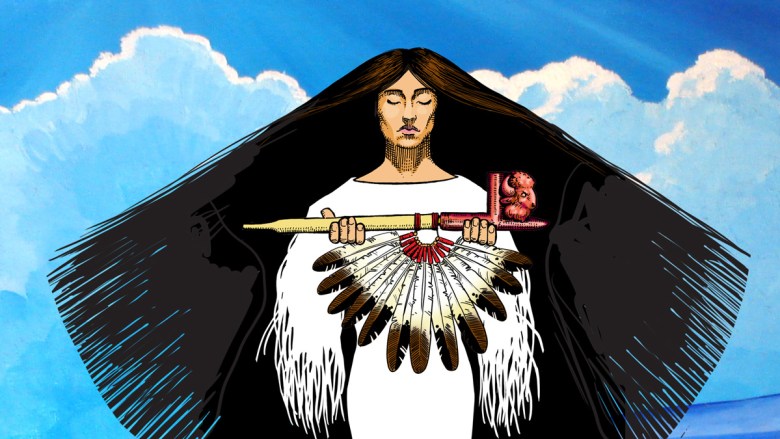

SDPB and Two Bulls developed a relationship with Maȟpíya Lúta School, formerly Red Cloud Indian School, where Lakota kids learn about the intertwined importance of restoring buffalo and revitalizing the Lakota language. At the beginning of Tatanka, Maȟpíya Lúta students use the language to tell the story of Pté Sáŋ Wíŋ, or White Buffalo Calf Woman, who brings teachings from the Great Spirit to the Lakota.

High Country News spoke with Richard Two Bulls about Tatanka: A Way of Life, which premiered on SDPB on Oct. 19 and is now available online hnow available online here.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

High Country News: I really like that children speaking Lakota relay the story of White Buffalo Calf Woman. Can you tell me a little bit about your decision to include that?

Richard Two Bulls: When we sat down and decided to tell this story, one of the biggest things for me was that I wanted to be able to highlight the story of the White Buffalo Calf Woman because it’s one of the very important stories related to buffalo. It teaches people who have lost connection with the Creator to get back to virtues such as respect and generosity.

I grew up with that story, and I’d never heard it told in Lakota by a young person. But I knew it could be done, because I’ve done a lot of reporting not only on Red Cloud, but on a variety of groups on multiple reservations that are trying to reintroduce the language and culture to the youth.

That opening scene was the highlight of the documentary for me. It was a beautiful thing to see, especially because I’m a part of that generation that wasn’t able to learn Lakota.

HCN: I think that’s why it spoke to me, too, because both my grandmas spoke Arapaho. But my mom didn’t learn it, so I didn’t learn it. And so to hear them speak and kind of stumble over their words — I just loved it.

RTB: This documentary looks at the buffalo from a modern perspective — at what tribes are doing with nonprofits and other groups to bring back the buffalo. And I wanted to showcase that. But I needed the White Buffalo Calf Woman story as a catalyst, to move the story from the history of what happened here, from the atrocities with boarding schools, to its climax.

People who aren’t used to being around Native Americans tend to focus on the negativity of what is happening today, with poverty and all that. So, I wanted to tell an empowering story with the White Buffalo Calf Woman’s story, and then go into the history, but to leave people with the thought that we’re not just existing out here, we’re doing things to bring back the culture and the tradition and the main food source that Native Americans existed on for thousands and thousands of years. It’s not lost. We’ve taken another path back to it, if that makes sense.

HCN: It totally makes sense. You had some illustrations intermixed in the documentary. Who did them?

RTB: The illustrations were done by my uncle. His name is Marty Two Bulls, Sr. He’s a pretty renowned artist and editorial cartoonist here in Indian Country, and he was a Pulitzer finalist in 2021. He already had a relationship with South Dakota Public Broadcasting, freelancing his artwork. I wanted to have this organic type of documentary, and I wanted to utilize as many Native Americans as possible in the production.

HCN: Was it planned or was it a happy accident that Tatanka is being released at the same time as The American Buffalo, the Ken Burns documentary?

RTB: It was a little bit of both. I don’t think I’d heard about the Ken Burns documentary until after we’d already done a story about the Maȟpíya Lúta School harvesting a buffalo with their students. They’d involved the community as well as a lot of staff and students. Young men were able to do the traditional cultural practices of ceremony in order to be able to hunt the buffalo and to understand what all of that means.

When we heard about the Burns documentary, we said, “Oh, why don’t we do something that’s really localized to the buffalo here within the state and the nearby regions,” because we knew the Burns documentary was going to be very grand-scale. There are something like 80-plus tribes with buffalo in the United States; he can cover that, while we can show people what it’s like here in our state. We can show what these schools and nonprofits are doing to regenerate these traditions and pass them on to future generations.

There are just so many narratives, and there’s no definition of what storytelling is — as long as you’re passing on what you learned from your elders, your parents and the culture and being able to find your experience and paint it, draw it, write it, it’s storytelling. What I wanted to do was inspire people and say, “Hey, I was a rez kid growing up, and I never thought I’d be in this situation.”

Taylar Dawn Stagner is a writer and audio journalist (Arapaho and Shoshone) who writes about racism, rurality and gender. Formerly, she was an editorial intern for HCN’s Indigenous Affairs desk.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.