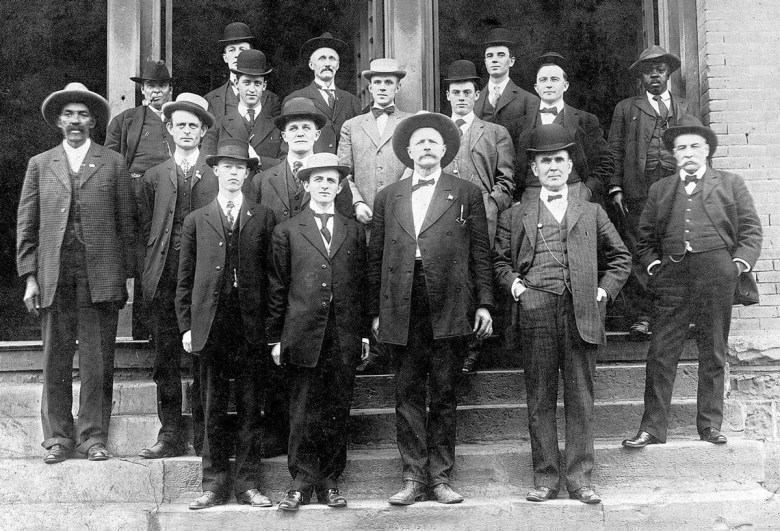

Cowboys — and by association the region they roam, the West — are, as a recent New York Timesarticle put it, having a moment. While the Paramount+ television show, Yellowstone, has gotten much of the shine, this particular “moment,” unlike those before it, has also featured multiple on-screen portrayals of the African Americans who, historically, made up a not insignificant portion of Western homesteaders and, yes, cowboys.

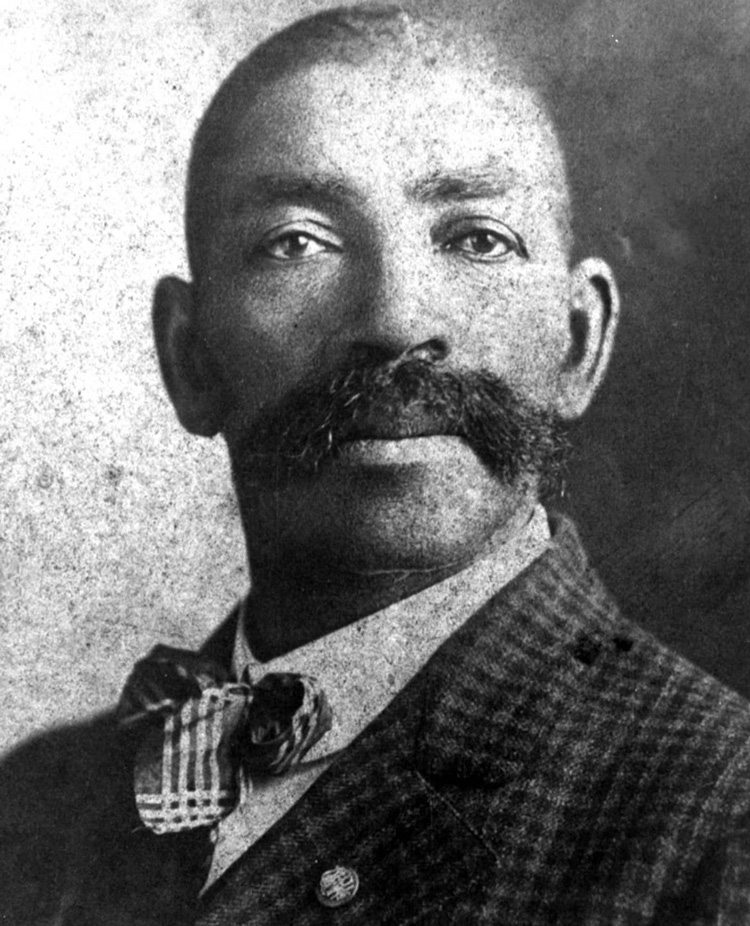

On Nov. 5, the Yellowstone universe expanded to include a miniseries called Lawmen, and the first lawman featured is Bass Reeves, a Black larger-than-life 19th-century U.S. deputy marshal. This is emblematic of a larger shift in Black representation that, if we’re lucky, may be here to stay.

Bass Reeves exemplifies both the opportunities available to people of color in the post-Civil War West and the importance of strategically navigating a variety of cultures and communities to obtain success within that time and space. A Black man who had escaped from his enslaver, learned several Native American languages and become familiar with the vast geography of Texas and Indian Territory (lands that would become the state of Oklahoma), Bass Reeves — the first Black man to serve as a U.S. deputy marshall west of the Mississippi River — was hired as because of his ability to straddle multiple worlds. He became known for his many successful captures (he is said to have arrested several thousand robbers, murderers, thieves and the like over the course of 30 years); his honesty, in a sphere in which this was a rarity), his shooting ability (he was a legendary marksman); and his innovative use of costumes to capture his quarry. He even brought in his own son when a warrant went out for the young man’s arrest for the murder of his wife.

While these exploits appear infinitely suited for television and movies, Reeves has only recently begun receiving his due, initially in 12 or so brief portrayals or mentions in media as wide-ranging as The Simpsons, Justified and The CW’s Legends of Tomorrow. Perhaps the most resonant of these was his cameo in HBO’s critically acclaimed Watchmen show (2019), where he appears less as a person and more as a symbol of the Black possibility quashed by racist violence. In Watchmen, as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre transpires around him, a child watches a film (created just for the show), starring Bass Reeves as the heroic enforcer of the law who takes down a white criminal. The film, as well as his own brush with death, inspires the Black boy, Will Reeves (his surname borrowed from Bass’ own) to later moonlight as “Hooded Justice,” a vigilante who solves crime, especially that related to Black oppression, and disguises himself not only with a hood, but also makeup, so that he appears to be a white man.

This is emblematic of a larger shift in Black representation that, if we’re lucky, may be here to stay.

Years later, Will turns the adventures of “Hooded Justice” and his fellow vigilantes into comic books and maintains the illusion that his alter ego is white. This mirrors the belief by many historians and popular culture experts that Bass Reeves served as the unofficial inspiration for the popular television show (and later film), The Lone Ranger, who was white. The Lone Ranger roamed the High Plains, solving crimes alongside his Indian sidekick, Tonto, who served, problematically, as comic relief. That Reeves’ Blackness was likely seen by the character’s originator as something that would’ve detracted from the audience’s ability to root for and empathize with him reflects the inability of many white Americans to see Black characters and Black people’s motivations and experiences as similar to their own. This is why the proliferation of television shows and films either focusing on Black people in the West, or at least featuring them, matters. And Bass Reeves has been part of this.

Netflix’s The Harder They Fall (2021) featured Delroy Lindo as Reeves, accompanied by a hodgepodge of famous historical Black figures in the West, including Cherokee Bill, Nat Love, Bill Pickett and Jim Beckwourth, few of whom likely crossed paths in real life. The film was not without its controversies, with many upset over the casting of light-skinned actress Zazie Beetz as the real-life dark-skinned Stagecoach Mary. Lindo’s Bass Reeves is a lawman who balances honor and duty. The film introduced viewers to the reality of Black Western settlements and whet their appetites for more stories about these men and women, who largely hadn’t played much part in popular culture until now.

While there were, of course, earlier films either centering Black cowboys (2020’s Concrete Cowboy, set in Philadelphia) or playing on Western tropes using Black characters (1993’s Posse or 2012’s Django Unchained), the success of The Harder They Fall ushered in a number of other films and television shows or miniseries on the Black West that received varying degrees of attention and positive feedback. For example, Jordan Peele’s Nope (2022) is about a community’s reaction to an alien, with the main characters being two Black siblings who live on a California ranch and make their living as Hollywood horse wranglers. 2022 also saw the release of Dead for a Dollar, wherein Brandon Scott’s Elijah Jones is an Army deserter who gets caught up in a classic Western revenge saga. See also: Surrounded (2023, starring Letitia Wright), Outlaw Johnny Black (2023), and even docuseries, like The Real Wild West.

As for Lawmen, actor David Oyelowo — who brings Bass Reeves fully to life and also serves as executive producer — told Vanity Fair that Reeves essentially represents the ironies of American history. In a question that a teacher might pose to middle schoolers, Oyelowo ruminated on Reeves’ decision to take his freedom in his own hands by running away: “If we can now say that the enslavement of people was unjust, then freeing yourself from that unjust circumstance, can that truly be deemed unlawful?” This sort of surface-level engagement with the complexities of Black life and identity is on display in the show. The show opens with Reeves being presented as almost a Confederate apologist, first implying in a conversation with a Black U.S. soldier that the Confederacy was preferable to the Union because they were at least upfront about their biases, and then receiving commendation for his military prowess from a kindly white Confederate officer. We know from Reeves’ own admission that he did, indeed, learn to use and master guns during his time in the war, so it is true that he functioned as more than a body servant. Yet, Reeves would have been well aware that he was only “serving” for the Confederacy because he was enslaved. If anything, the complexity to be explored here is that he may have felt guilt when encountering other African Americans. There are signs of unhappiness, but they are telegraphed, whereas signs of supposed Confederate inclusion and active involvement are blatant.

This sort of surface-level engagement with the complexities of Black life and identity is on display in the show.

It’s not all bad. In the first two episodes, at least, the show accurately represents the prejudice Native Americans faced, contrasting it with the worldview Reeves was widely said to hold: that all people, regardless of ethnicity, should be treated equally; he pushed back against stereotypes that saw Native people mischaracterized as savage criminals and treated as such. However, Reeves is shown feeling more emotion over his part in the dishonorable takedown of a Choctaw criminal than the fact that he was forced to fight for, and with, his enslaver during the Civil War. Perhaps more introspection will come in a later episode of the remaining six.

Black Westerns offer the opportunity for Black actors to inhabit the gamut of humanity, from kindhearted settler to kickass sheriff (or deputy marshal) to morally ambivalent gunslinger. With a man like Bass Reeves, who had to navigate white racism, tribal sovereignty and African American identity politics, we could have been that much closer to arriving in an era in which Black life onscreen is reflective of the complexities and cross-cultural realities of Black life on the ground. But we’re not there yet. Perhaps the yet-to-be-released HBO project, Twin Territories, co-produced by Morgan Freeman and also based on Bass Reeves’ life, will fare better.

Alaina E. Roberts holds a Ph.D., is an associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh and is the author of I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land. Follow her on Bluesky @alainaroberts and Instagram @phddiva7. We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.