I am the child of a Chinese immigrant father and a white American mother, and I grew up amid the sunlight and saguaros of Tucson, Arizona.

As a kid, I had no idea about the long and rich history of Chinese people in Tucson. In school, we were taught a history of America that appeared to take place only in California, New York and Washington D.C. Not here.

The few Asian kids I knew were like me — the children of immigrants, relatively new to Tucson.

So when I learned about a pink-haired fashion designer-turned-chef’s desire to draw attention to a food that symbolizes the historic relationship between Chinese and Mexican communities in Tucson, I was captivated. I began reporting on the Chinese Chorizo Festival because I hoped it might finally give me some answers about what it means to be a Chinese American from Tucson, where less than 3% of the population is Asian.

FENG-FENG YEH, who grew up in Tucson, is the child of Taiwanese immigrants. Last year, she launched the Chinese Chorizo Project, a campaign to raise awareness about the “historic food fusion” that is Chinese chorizo, a sausage that Chinese grocery store owners created in the mid-20th century for their largely Mexican and Indigenous customer base.

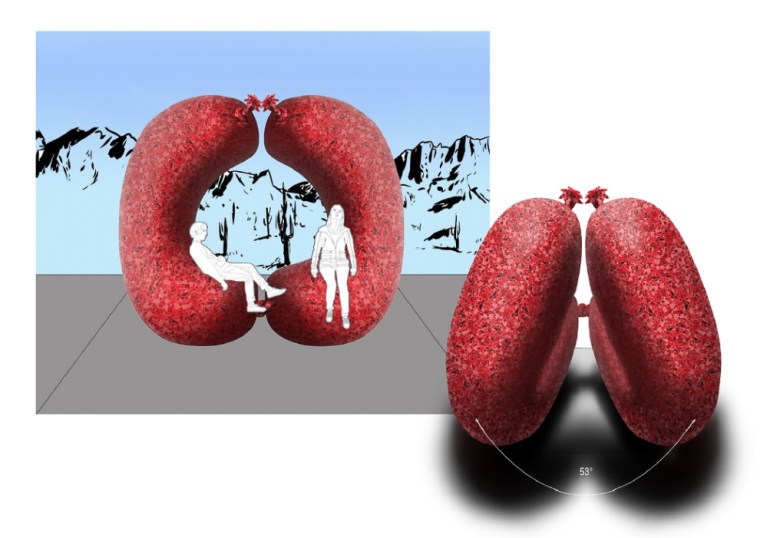

The project features a monthlong festival designed to help garner community support for erecting a unique public sculpture — a 15-foot mosaic — showing two sausage links in the shape of a heart. The sculpture is still in the fundraising phase. Meanwhile, the project’s larger goal is to help Tucson and the state of Arizona recognize “the history of Chinese and Mexican immigrant solidarity,” Yeh said.

The Don family, who have been in Tucson since the early 1900s, are part of that history.

Kathleen Chan said that her grandfather once worked as a cook for the Chinese laborers who helped build the Southern Pacific railroad. Later, he settled in Tucson and opened a grocery store. Her mother grew up in Tucson, speaking Spanish with the neighbors and Cantonese at home; she only learned English when she finally started school.

The family had 10 kids; Chan’s uncle, Philip Wah Don, was the only boy. In the 1950s, Wah Don opened what soon became Tucson’s first and only Chinese and Mexican deli — El Cortez Market.

“I think chorizo became a major part of Chinese family stores because their customers were Hispanic.”

According to Wah Don’s son, Philip Don Jr., when El Cortez Market began making and selling chorizo in the 1970s, it was a part of a strategic move to stave off the threat of big-box chain grocery stores. The store’s produce and frozen sections had become unprofitable, so the family converted the store to a meat market.

“That’s what really kept them in business,” Don said. “I think chorizo became a major part of Chinese family stores because their customers were Hispanic.”

Chorizo is a sausage made from the leftovers of other meat products. It’s like the sausages in European countries, “except we added the chilis to it and that red color. So that makes it uniquely Mexican,” said Carlos Valenzuela, a Chicano artist and educator who partnered with Yeh on the sculpture project.

“It’s very connected to working-class people, particularly Mexican people,” he said.

Don said that his father’s recipe came together when he took some of the meat that his customers weren’t buying, added spices and chili powder and then used red wine to blend everything together.

As part of this year’s Chinese Chorizo Festival, Yeh is making around 1,200 pounds of Chinese chorizo, which she gives free of charge to participating restaurants in Tucson and Phoenix.

Last year, she partnered with Maria Mazon, chef and owner of Boca Tacos, and Jackie Tran, a food writer and owner of the food truck Tran’s Fats, to develop a modern recipe for the chorizo.

“I made some modifications using some local wine, and I also substituted some of the generic red chili powder with some specific types of chili peppers to create a more complex profile,” Tran said.

Each restaurant is free to use the chorizo however it likes. Recently, on a trip home to Tucson, I finally got to try the sausage. I bought a Japanese onigiri from Fatboy Sandos, which serves “Japanese-inspired sandwiches y más” and is a modern example of cultural fusion.

The Chinese chorizo was bundled in rice wrapped in seaweed. I dug through the rice until I reached the sausage. It was savory, with a tang from the wine. I could taste the saltiness of the soy sauce and just a hint of spice from the peppers.

I don’t know how to describe it, other than that it tasted both deeply American and deeply Chinese.

VALENZUELA’S MOSAIC MURALS glitter in South Tucson and on the Pascua Yaqui Reservation. His family’s history in Tucson runs deep; his great-grandparents came to Tucson after the Mexican Revolution, fleeing persecution and death at the hands of the Mexican government.

Last year, Yeh reached out to him to create a sculpture for the Chinese Chorizo Project.

“I told my family what I wanted to do, and they were like, ‘You’re gonna make a big chorizo?’,” he chuckled.

The sculpture, whose location has yet to be chosen, will feature ceramic tiles with Mexican and Chinese symbols. Yeh said that she plans to start a ceramic workshop with different artists and ask the public to submit tiles.

“From a distance, you’ll see this big red heart glimmering in the sunshine,” Valenzuela said. “As you get closer you realize that they’re chorizo-shaped … and then as you get closer still and put your hands on it, you’ll realize that there’s all these symbols.”

Yeh sees the sculpture and festival as “a way to modernize the solidarity from the past by re-creating new bonds within our community.”

Her partnership with Valenzuela is a symbol of those efforts.

Valenzuela’s grandfather, an orphan who survived Mexico’s revolutionary war, used to shop at Jerry Lee Ho’s market, in Barrio Viejo, the oldest neighborhood in Tucson. According to local historian, Sandy Chan, the market was open for over 100 years and was run by four generations of the Lee family.

“He had credit at all the Chinese stores in Tucson,” Valenzuela said.

“There’s this tremendous history that the Chinese could find a home in our communities in … the Southwest, which used to be Mexico,” Valenzuela said. “It’s epic. It’s a story of survival.”

He sees the Chinese Chorizo Festival, and the sculpture, as an introduction to that history.

But at the same time, Valenzuela pointed out how the neighborhood that Jerry Lee Ho’s market was in has been heavily gentrified.

“Tucson is undergoing some tremendous changes.”

This gentrification began in the late 1960s, when an urban renewal project razed much of Barrio Viejo to build the Tucson Convention Center. The project displaced a vibrant Mexican American community that was home to many Chinese grocery store owners and their families in order to “bring those white dollars down to the barrio,” according to Alisha Vasquez, a fifth-generation Tucsonan and director of Tucson’s Mexican American Heritage and History Museum.

The building that housed the market is now an environmental consulting firm. The only trace of its former use is a mural that depicts an apron-clad grocer surrounded by plants and people of the barrio.

“Tucson is undergoing some tremendous changes,” Valenzuela said.

Valenzuela said that he wouldn’t be able to afford his home if he had to buy it again now.

“It’s tragic because (Tucson) was friendly to artists for a long, long time,” he said quietly. “Those days are gone.”

Yeh said she chose the slogan for the project, “Ask how the sausage gets made,” for this very reason — to recognize “these unsavory moments in history.”

However, Valenzuela said Chinese Chorizo Festival itself is symbolic of the changes Tucson has been undergoing.

“I like it. But it adds to the value of the place. And that’s not always necessarily a good thing,” Valenzuela said.

Reia Li is a senior anthropology major at Pomona College, where they write for the college newspaper, The Student Life. An aspiring journalist, they are passionate about reporting on Tucson, Arizona, and the Southwest. We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.