In 2000, Sam Lea converted his once-productive Willamette Valley onion field back into wetlands. The third-generation Oregon farmer excavated several ponds and largely left the land alone. Soon, willows arrived on the wind. Then tule appeared. About five years ago, he noticed wapato had sprouted. The edible tuber, a traditional food for Pacific Northwest Indigenous peoples, is now flourishing. The greenery covers 70 acres. “If you look at it now, you’d think we planted it all,” Lea said.

Wapato was once abundant but hasn’t grown here since the early 1900s, when Lake Labish, a shallow body of water 10 miles long and north of Salem, was drained for farming. Historic accounts describe Molalla people gathering tubers in the area. “There’s a significant seed bank in the soil,” said David G. Lewis (Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde), an Oregon State University anthropology and Indigenous studies assistant professor who descends from western Oregon’s Takelma, Chinook, Molalla and Santiam Kalapuya peoples. “If you leave it alone, (plants) will come back.”

At Lake Labish, cattails, tule, willows and wapato grew over thousands of years. Farmers erased evidence of the lake above ground, but belowground, decomposed vegetation that extends some 19 feet back in time preserved seeds and roots, retaining both ecological memory and a possible future.

Lea assumed that swans or geese spread the wapato seeds. But water collected in the ponds he made could have reawakened long-buried tubers, souvenirs of plants that lived before the lake was drained. At other Northwestern agricultural sites, native plants have also returned, unseeded, once crops or invasive plants were removed. In an era of ecological dread, endless development and rising global temperatures, it’s hard to believe that plants could endure, and even regrow.

Many plants store future generations just a few inches belowground in seed banks, where seeds, roots, buds and bulbs remain dormant. Some seeds can survive for decades — even centuries, or longer. Seed banks are “biodiversity reservoirs,” as one recent study described and are found in ecosystems globally. Across the West, they’re present from wetlands to deserts, sand dunes and sagebrush steppes. The plants wait until conditions are just right to reappear.

To Native scientists like Lewis, they offer a new possibility, that despite generations of degradation, some landscapes can come back. Northwest plants evolved unique seed structures, hardy root systems, long-living bulbs and complex dormancy periods to survive in landscapes that faced regular disturbance by everything from volcanic eruptions to flooding, drought, fire and colonialism. Yet non-Native scientists often overlook their ability to regrow — natural regeneration. It’s a tool in restoration ecology that is both understudied and written off even though it’s cheaper — and better — at creating resilient biodiverse landscapes.

“There is value to pausing and seeing how sites respond, letting the landscape talk to you and not try to force something.”

“A large part of the urge to plant is this feeling, like, ‘We broke it. We need to fix it,’” said Robin Chazdon, a senior fellow at the nonprofit research organization World Resources Institute. Chazdon, who is based in Boulder, Colorado, co-authored a 2017 policy brief that urged ecologists and others to consider natural regeneration. For 30 years, she has studied forests in Mexico, Costa Rica and Brazil. Tropical forests, including mangroves, can regrow better on their own, without any plantings, her research found. “We don’t want to work against nature,” she said. “We want to work with nature. And nature’s figured out over these billions of years how to recover.”

Experts say restoration can be one-size-fits-all: Kill the weeds, then plant native seeds. But it’s hard to get seeds to grow and some might not be genetically adapted to the site. Collecting and planting native seeds is the foundation of the Department of the Interior’s new National Seed Strategy Keystone Initiative, which Secretary Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna) said will “help ensure we get the right seeds, in the right place, at the right time to restore our public lands and bolster climate resilience.”

Many non-Native scientists question whether restoration isn’t possible without planting because seed banks are either depleted or can’t replenish damaged landscapes fast enough. There’s an urgency, they say, given the climate and extinction crisis. If native plants return quickly, pollinators, fish, birds and mammals — a functioning ecosystem — might follow.

But this approach is based on the assumption that we can rush ecological processes that have evolved over millennia. It ignores tribal land-management perspectives that value time and trust. Plants return to ecosystems in stages. Some reappear rapidly, others don’t. Some tribal scientists say that if traditional ways of caring for landscapes, through fire, harvests and seasonal flooding, return, plants will also return. So will pollinators, fish, birds, mammals and cultural connections to them, restoring a way of life, a long-term relationship between people and place. It’s a process that lacks a quick fix, or high-tech solution. “Tribal people, we think decades ahead, seven generations ahead,” said Ashley Russell (miluk Pamunkey k’a’uu), assistant director of culture and natural resources and a citizen of the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians of the Oregon Coast. “Because we plan so far ahead, we’d like to take our time.”

Natural regeneration is neither passive nor naive. People can create conditions that encourage plants to regrow. Several tribally led projects in the Northwest combine Western science with Indigenous science. The Yakama Nation in central Washington transformed a 400-plus-acre barley and wheat field back into wetlands once scientists recreated the water flow through the floodplain. The Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians restored an 88-acre estuary by excavating tidal channels, allowing water to naturally revegetate the marsh. Birds, wind and water, a network of relations, helped disperse seeds. Restoration projects must first return key ingredients, like water or fire, that require an active relationship with the landscape. Without that, one former Yakama biologist said, restoration becomes more akin to farming or gardening than restoring true ecological functions. When the right conditions are present, the results are stunning.

Prairies

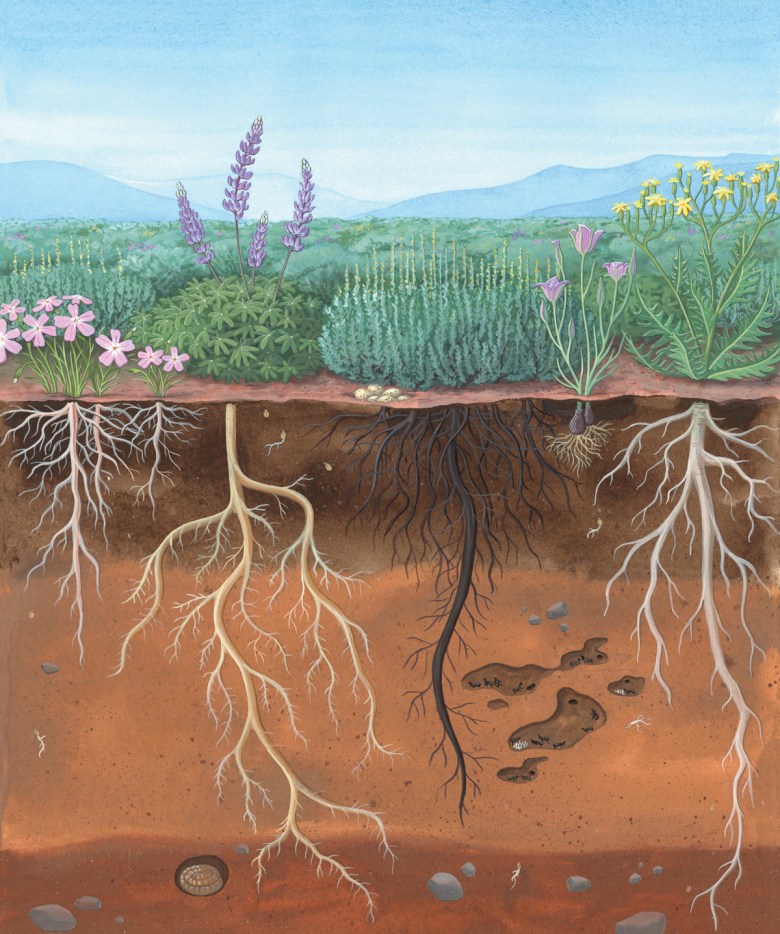

Lupine embryos slept underground, protected by seed coats like ceramic shells. Above them, cattle grazed for decades under sprawling oaks. Invasive Scotch broom, Himalayan blackberry and thistle grew profusely in this western Oregon pasture.

A few years ago, the lupines woke up. Sunlight warmed the soil. Rain seeped down, just a few inches, to a tiny pore at the top of each seed. Weeks later, teardrop-shaped lavender petals bloomed in the April sun. The plants may be Kincaid’s lupine, a Willamette Valley prairie species that was once abundant in the open oak grasslands bordered by the Cascades to the east, and the Coast Range to the west. Since 2000, Kincaid’s lupines have been listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

This 60-acre pasture lies within the ceded lands of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. When the tribe reacquired it in 2019, Lindsay McClary, the tribe’s restoration ecologist, noticed that a few lupines appeared once Scotch broom was removed. Both lupines and Scotch broom belong to the pea family, and their hardy seeds can persist underground for decades — up to 80 years for Scotch broom. No one knows just how long native lupine seeds can survive.

McClary approaches sites slowly. She observes properties carefully before she sows anything. Dry prairies in the Willamette Valley are challenging. Invasive species, especially grasses, have choked out natives for decades; thick brown thatch covers the ground. Non-Native ecologists believe invasive seeds outnumber natives in the seed bank, but no studies have confirmed it.

After removing invasive species, McClary often plants seed from locally sourced native bunch grasses, like Roemer’s fescue, to crowd out any returning invasives. Then, she’ll wait and see if any native flowers appear. She hasn’t seeded anything at this property, yet the lupines have spread to around 25 individuals now. “There is value to pausing and seeing how sites respond, letting the landscape talk to you and not try to force something,” McClary, an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians of the Great Lakes Basin, said.

“Maybe the seed bank is there, and maybe it can take care of itself, and it just needs a little bit of time.”

AT OTHER GRAND RONDE properties, Oregon iris emerged in a former horse pasture. Oregon sunshine, strawberry and several species of checkermallow also sprang from the seed bank once invasive species were removed. Camas, a traditional food with star-shaped indigo flowers, has regrown throughout the valley. On one site west of Portland owned by Linfield University, the wildflowers covered half an acre after blackberry was cleared. Camas evolved with annual harvests and fires by Kalapuyan families, who lived in the Willamette Valley. If the edible bulbs aren’t harvested frequently, or if nonnative grasses crowd them out, they’ll withdraw deep into the ground, sometimes by an arm’s length, in search of water. The bulbs can live for decades. As soon as favorable growing conditions return, they send new shoots up through the soil.

Some Grand Ronde tribal members were not surprised.

“They’re kind of sitting there, waiting for those opportunities,” said Greg Archuleta, a tribal member who works for the tribe’s cultural resources department. A few years ago, he said, a small fire burned a landscaped patch off I-205 that runs through east Portland. Afterward, several native plants that weren’t there previously, including black raspberry, sprouted. Archuleta visited a few privately owned properties in the Kings Valley area north of Corvallis, where native plants appeared on their own, once landowners thinned the oak understory.

After white settlers arrived in the mid-1800s, the Willamette Valley’s rich prairies and wetlands became farms, cities, shopping centers and vineyards. Despite broken treaties and exploitation, native seeds and bulbs survived underneath onion fields and pastures. This reassures Archuleta. Other tribal elders also trust that native seeds wait underground and can return.

Still, many non-Native ecologists overall consider natural regeneration more of an ecological fantasy than a successful approach to restoration. “There are these interesting exceptions that tantalize us,” said Tom Kaye, an ecologist and executive director for the Institute for Applied Ecology, a Corvallis-based restoration nonprofit. But typically, only a handful of plants return, and he wants a million. “If we don’t plant native seeds,” he said, “we don’t get native plants.”

Such philosophical differences play out in different restoration strategies. Nontribal projects operate on short timelines. Public grants for restoration typically fund three to five years of work but often lack money for long-term monitoring. Grantees want certainty, a guarantee that so many acres will be seeded with native plants, so ecologists often turn to herbicides, then sow native seeds. It’s cheap and quick, but the projects tend to be cookie-cutter, a step-by-step recipe for undoing colonization on the landscape.

The Institute for Applied Ecology eradicates nearly everything using glyphosate-based or grass-specific herbicides like those found in Rodeo, Gly Star and Roundup. Over a two-year period, they spray multiple times a year, including in the spring. That keeps invasive plants from producing seed, but also kills any remaining native plants. Then workers plant locally sourced native seeds, at a cost of $333 to $826 per acre. Sometimes about half of them don’t germinate, Kaye said. Weather, soil chemistry and the amount of weeds in the seed bank all complicate the effort.

Local farmers wondered why the tribe had drowned perfectly good farmland. The tribe wondered if, after more than a century of agriculture, native plants, and eventually salmon, would return.

A few years ago, the Institute tried a different approach. Tall nonnative grasses dominated a seven-acre site east of Salem, though some native plants persisted. Workers applied glyphosate twice, in December 2021 and fall of 2022, when nonnative grasses germinate while native flowers are still dormant. The past two springs, delicate white flowers of native saxifrage covered the meadow. A few months later, native yellow monkeyflower brightened all seven acres. The plants weren’t seeded.

At sites owned by the Grand Ronde, McClary initially removes large swaths of invasives in the fall using chainsaws, masticators or mowers instead of herbicides. Like many tribal ecologists, she develops an intimacy with the properties. When restoration of a landscape means bringing back not just plants, but the interaction between people and plants, the work becomes something more than grant timelines and budgets can consider.

Eventually, the tribe wants to manage its sites using fire every three to five years. It will take years and multiple burns to diminish the invasive seed bank, Archuleta said. Restoration requires even more careful thought in areas that are contaminated by chemicals found in local soils — DDT, PCBs, lead, arsenic and compounds from herbicides that prevent safe consumption of First Foods. “We’re not trying to help restore this and hope tomorrow that we can go and gather there,” Archuleta said. “We know and understand that some of these are gonna take time. We come from that mindset, of the patience that’s needed.”

Estuaries

Over a century ago, Ole Matterand built a house where Puget Sound’s tide once moved in and out, twice a day, every day. Near the mouth of northwest Washington’s Stillaguamish River, with rugged mountains to the east and west, Matterand and other Norwegian immigrants turned the area’s salt marshes into fields for grains and other crops in the 1870s.

Matterand’s 88-acre property followed a prominent oxbow along the Stillaguamish River just south of Stanwood. He built miles of levee and worked aggressively to keep the tide, and the Stillaguamish people, out.

The farmers prospered, but salmon populations plummeted. As many as 30,000 chinook once returned to the Stillaguamish to spawn. Now, just 725 wild fish travel back. By the late 1960s, farms and development had replaced

85% of the estuary where young salmon fed in tidal marshes before heading to the ocean. Two runs of Stillaguamish chinook — summer and fall — were listed as threatened in 1999. A watershed-wide recovery plan followed.

By then, Matterand’s grandson, Stanley Matterand, had inherited the property and was leasing the land to farmers. He had no interest in salmon restoration. When the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, in the early 2000s, asked if he’d consider selling, he replied, “Not until I’m dead and in the ground.”

Then, in 2010, at the age of 89, he died.

No one in his family wanted the farm, and the state agency no longer had the money. The family reached out to the Stillaguamish Tribe, which purchased part of the property in 2012. Five years later, they tore down the dilapidated house. They breached the levee and built a new, smaller one farther from the river and Puget Sound that protected nearby farms while still allowing water to flood the site. They named the property “zis a ba,” after a prominent tribal member who lived in the area in the 1800s.

For the first time in 140 years, brackish water returned to the 88 acres. The salinity killed the remaining crops. A juniper planted near the house lost its needles.

Local farmers wondered why the tribe had drowned perfectly good farmland. The tribe wondered if, after more than a century of agriculture, native plants, and eventually salmon, would return. “A lot of the agricultural folks that we talk to say, ‘Well, that habitat is gone. You can’t restore that,’” said Jason Griffith, the tribe’s environmental program manager. “Actually, it’s pretty easy to restore.”

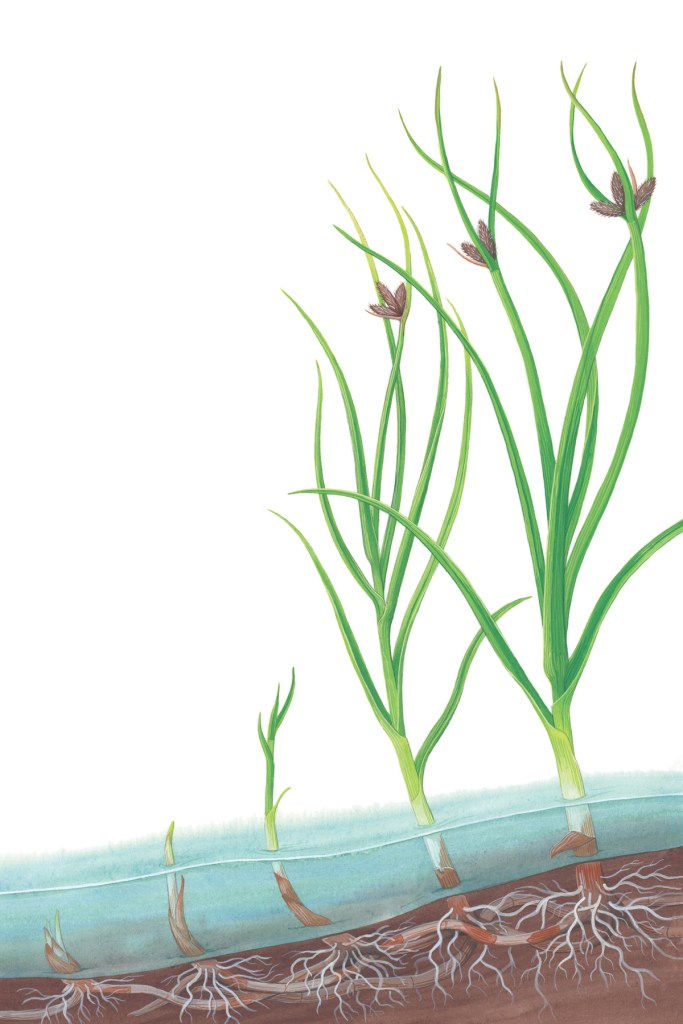

A few months after the tides returned, maritime bulrush poked through the mud. By the next year, the plant had spread to the horizon. “It was an instant meadow of maritime bulrush,” said Greg Hood, a research scientist with Skagit River System Cooperative, the natural resource management agency for the nearby Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community. Hood worked with Griffith on zis a ba’s restoration plans. “I’ve never seen anything restore so quickly,” Hood said. “It was stunning.”

In early July, Hood and Griffith wandered the site, navigating through sedges that reached to their hips. It’s even thicker now, Griffith said, smiling. Seaside arrowgrass’ spindly budding stems stretched toward the blue sky. In a few weeks, its small purple flowers would color the marsh.

Nothing was planted. The seeds came in with the tide.

“There’s just a big melange of seeds swirling around in the tidal waters of Puget Sound,” Hood said. Nearby remnant marshes that were never developed, like those in Port Susan Bay south of zis a ba, provide enough native seeds. Tides have naturally reseeded other Puget Sound estuaries. Under the right conditions, seeds will float in, then grow.

SOME PEOPLE with the project were skeptical when Griffith proposed not revegetating. “Where’s the planting plan?” they asked.Griffith joked that he could have handed them a tide chart: “Here’s the planting plan. Twice a day, that’s when they get planted forever.”

Simply breaching levees, though, isn’t enough. Over decades, heavy agricultural equipment compacted the soil, creating an impervious clay layer up to five feet thick. “We used to think that you could just let the tides carve the channels and nature would know where the channels should be,” Hood said. Water eventually erodes channels, but salmon can’t afford to wait.

Hood has spent several decades studying Puget Sound’s tidal marshes. Before white settlement, thickly vegetated marshes would have kept the channels — the veins of the estuary — shaded and cool, full of insects for young salmon to eat. He developed a mathematical model to predict how many channels and tidal outlets a site should have. At zis a ba, it recommended three miles, with seven outlets for salt water to move in and out. The channels vary in length, width and depth. They spread water across a more textured surface and allow seeds to settle. Without enough channels or outlets, high-velocity tides scour seeds away.

At Fir Island Farm Estuary Restoration Project, for example, north of zis a ba, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife constructed more than two miles of channels in 2016. According to Hood’s model, there should be about 6.8 miles weaving through the 131-acre site. Tides funnel through just one outlet when Hood thinks there should be somewhere between 12 and 20. Much of the property resembles a mudflat more than a marsh. The state seeded 12 acres, spending $20,000 on seeds that Hood believes likely washed away. Altogether, the project cost $16.4 million.

Restoration science is relatively young, and scientists have only been restoring tidal marshes in the area for about 20 years. When construction began on Fir Island, scientists had faith that water could carve channels. But people first have to step in to prepare the site, then trust that the plants will respond.

IN THE 1980S, the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians voluntarily ceased commercial fishing of chinook salmon, citing their critically low numbers. Kadi Bizyayeva was among the first generation that was unable to harvest chinook.

While almost 150 years of agriculture is a long time from a human perspective, to a landscape, it’s the blink of an eye, said Bizyayeva, a tribal council member and the tribe’s fisheries director. “Almost as soon as the habitat was re-established, we saw fish” in zis a ba, she said.

The tribe recently purchased two more sites nearby. Between all three, about 718 acres will become salt marsh again, filled with plants brought by the tide, twice a day, every day.

SAGEBRUSH STEPPE

On Aug. 10, 2015, lightning struck a hay bale in southwestern Idaho’s Owyhee Mountains not far from Boise, just outside the northern Great Basin. Fire ripped through rolling hills and sagebrush-speckled rocky outcrops. About 280,000 acres burned, almost all of it greater sage grouse habitat that is largely owned by the Bureau of Land Management. The Soda Fire was the first massive blaze to occur after then-Interior Secretary Sally Jewell ordered agencies to do a better job of restoring burned sagebrush landscapes. A few weeks after the fire, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service opted not to list sage grouse under the Endangered Species Act.

The Soda Fire gave the BLM an opportunity to show that it could improve sage grouse habitat. Overgrazing, agriculture and energy development facilitated by the agency transformed the birds’ home. The once-vast silver-green landscape shrank to just 56% of what it was. Wildfires fueled by invasive cheatgrass also threaten the ecosystem. “We’re working for the survival of the sagebrush landscape,” Idaho State BLM Director Tim Murphy told the Idaho Statesman at the time. “We have to push the limits on seed, herbicide and equipment,” T.J. Clifford, the post-fire rehabilitation team leader, said. To crowd out cheatgrass, they said, they needed seed — and lots of it.

A few months later, the BLM sprayed thousands of acres with herbicide from a helicopter and sowed 1.6 million pounds of seed, spending nearly $30 million over several years. Some seeds were sagebrush, but others were cheaper, readily available nonnative grasses and flowers and native grass cultivars that lack extensive wild traits. Most cultivated native seeds are collected outside the Great Basin, grown on farms and not adapted to the Owyhee Mountains, raising the question: Are they still native?

“Native versus nonnative, it’s not a binary thing,” said Matt Germino, a U.S. Geological Survey supervisory research ecologist who studied the Soda Fire. “It’s actually a gradient.”

Most “native” grass seeds available to federal agencies for large-scale restoration are cultivars. Grasses are easy to grow, and cows like them. Some, like Sherman big bluegrass seeded after the Soda Fire, were selectively bred to grow bigger, taller and earlier in spring, becoming uniform crops that are more useful to cattle than to sage grouse. Others haven’t undergone such intensive selection. If they’re collected from wild populations near restoration sites, they’re considered more “native” — “kind of native,” as Germino said. But under any selection, plants lose genetic diversity critical for long-term survival. Native plants have figured out how to persist in certain places. Some develop biological bet-

hedging strategies to have long-lasting dormancy periods until growing conditions are just right. They’ve adapted to particular soils, precipitation and elevation, and they pass on that genetic knowledge to future generations through their seeds.

In the 1930s, after drought and overgrazing eliminated vegetation from sagebrush lands and caused severe floods, the U.S. government developed grass crops to stabilize soils and restore grazing lands. After wildfires, BLM land managers similarly scramble to find seed on short timeframes, often choosing the cheapest, fastest-growing grasses to stabilize soils, outcompete cheatgrass and satisfy ranchers. One 2005 federal paper suggested that such widespread cultivar plantings may have “irreversible genetic and ecological effects.” BLM officials, however, simply call the seeds native. “It’s not necessarily the best thing to put back out on the land,” said Nancy Shaw, a scientist emeritus for the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station. “That’s been kind of an ongoing battle.”

For decades, scientists like Shaw researched and advocated for more careful collection and growing of native plants so that their genetics remain unaltered. The BLM is part of the DOI’s National Seed Strategy Keystone Initiative to increase the amount of genetically appropriate seed for restoration that was projected to cost an estimated $360 million from 2015 to 2020. The Biden-Harris administration has allocated $218 million for national seed efforts so far. But such an ambitious endeavor is still years out.

Many researchers say intensive seeding efforts might not be needed in some areas after fires, since long-living dormant seeds persist underground. “Some of these places have pretty impressive seed banks post-fire,” said Sarah Kulpa, a restoration ecologist and botanist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Reno. “People don’t think about this in sagebrush.”

ROGER ROSENTRETER walked slowly, scanning the ground, hands stuffed in jean pockets. The retired BLM botanist carefully observed plants growing on tan hills that burned in the Soda Fire. Fierce winds can whip through this area at 4,200 feet, but the weather was calm for mid-November. He rubbed the narrow leaves of one sage plant, smelled them and identified the species, noting its sharp, sweet smell. After 35 years of working in arid ecosystems, including 26 as the Idaho state botanist, he is an expert at identifying the shrubs.

“This is what was here before,” Rosentreter said, bending down to rip off a bit of early sage, a low-growing, tiny-leaved species. The petite shrub survived the fire. It’s the preferred winter food for most animals here. At many of Idaho’s largest leks, where male sage grouse perform their intricate mating dance and vocalize otherworldly melodies, early sage is the most common species.

But the BLM didn’t seed early sage. Much of the local vegetation and soil wasn’t inventoried before fire blackened the hills, and land managers didn’t know exactly which shrubs grew here. They relied on broad scale soil maps that failed to consider that even the slightest change in soil type or elevation can determine which species grows where. “People like to generalize and not really get into the details,” Rosentreter said. “It’s hurt sage grouse.”

With over 20 species and subspecies, sagebrush are easily confused, yet ecologically distinct. Big sagebrush, the most common type in the West — the kind most people imagine when they think of sage — has a handful of subspecies that evolved to grow in different soils and at elevations with varying precipitation. When they’re planted elsewhere, they might grow for a few years, even decades, but still not survive long-term.

A network of relationships is revived when water is the first to return to the landscape. Ecological memory is awakened, and foods regrow. A promise kept.

Commercially available sagebrush seeds often come from basin big sage, a subspecies of big sagebrush. It’s too time-consuming to grow agriculturally, so its seed can only be collected by hand from wild plants. Many seeds are gathered in Utah or Nevada. Basin big sage prefers well-drained soils, like roadside ditches, and produces massive seedheads, convenient for seed collectors. But sage grouse rarely, if ever, eat it. The shrub didn’t grow naturally in the burned site Rosentreter visited. The BLM seeded it from a helicopter.

Now, basin big sage grows next to Wyoming big sage, next to mountain big sage, next to early sage. Emerald leaves in clusters of three stand out among the muted green shrubs: Alfalfa. The crop was seeded on about half of the burn. Rosentreter noticed Sherman big bluegrass, a tall cultivar, not far away. It’s a mishmash of species, a hurried attempt at restoration that falls short of our obligations to the local residents — the sagebrush, pygmy rabbits, golden eagles, Morrison bumblebees, pronghorn, sagebrush lizards, harvester ants, bighorn sheep, burrowing owls and sage grouse.

WETLANDS

Eighteen-year-old Emily Washines waited in line for food with her mother at an event hosted by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe in northwestern Idaho. Her mother glanced into a large cooking pot. “That’s wapato,” she told Washines. “We used to have that, but we don’t anymore.”

The offhand comment struck Washines (Yakama Nation). Wapato: She recognized the name from a central Washington city on the Yakama Nation’s reservation, where she grew up. It must be important if a town is named after it, she thought.

More than a decade later, in 2010, Washines was in graduate school at Evergreen State College in Olympia. She asked her husband, a fellow Yakama Nation tribal member, what topic he’d suggest for her capstone project. “I would do it on the return of the wapato,” he said.

Wapato is a potato-like tuber that grows in thick patches along slow-moving water. The plant hadn’t grown on the Yakama Reservation for at least 70 years, not since white settlers drained wetlands for farms.

Beginning in the 1990s, Yakama Nation scientists, including Washines’ husband, an archaeologist, worked to transform a more than 400-acre barley and wheat field along Toppenish Creek into wetlands. The property was surrounded by farms, not far from the dry, shrubby foothills of the eastern Cascades, and the glaciated Mount Adams. First, water returned after levees were breached. A few years later, tule appeared. Willows, roses and currants followed. Then, emerald leaves sprouted — wapato. Scientists planted nothing.

At the site, called Xapnish, wapato’s return surprised everyone, even tribal elders. “They wanted to just go and see it,” said Washines, who at the time worked as the remediation and restoration coordinator for Yakama Nation Fisheries. She took several relatives, including Johnson Meninick, out to the site. Meninick served on tribal council during the 1970s, when the Yakama Nation first prioritized returning land to historical use, especially along waterways. Once he saw the familiar leaves, he had flashbacks: He visited the area as a child, when family members gathered the starchy tubers for dinner.

Washines grew up hearing stories about First Foods. At the ceremonial table where they are served, water is poured first. Then the other foods follow. Generations ago, the people made a promise. They would speak for the foods, remember their order, and take responsibility for them. In return, the foods would care for the people.

A network of relationships is revived when water is the first to return to the landscape. Ecological memory is awakened, and foods regrow. A promise kept. At Xapnish, tribal elders say the land is teaching us something, Washines said. “And we need to take it in.”

IN THE YAKIMA VALLEY and elsewhere in the West, water historically flowed heaviest in spring. Mountain snowmelt gushed down rivers, and water covered floodplains until summer, when flows dried up. “That is the driver of most river ecology in the West,” said Tom Elliott of Yakama Nation Fisheries, who worked on the Xapnish property. Fish migration and riparian plant regeneration evolved with spring flooding, he said. Irrigated agriculture turned this process upside-down. Reservoirs and water diversions now catch spring runoff and release it slowly throughout the summer for crops.

Toppenish Creek’s floodplain was so altered by farming that scientists had no historical remnant to reference when the tribe required the property. They weren’t sure what to restore, said Tracy Hames, a biologist who helped lead the project. Tribal elders took Hames and other scientists to the site several times and recalled how their relatives paddled canoes 20 miles upstream, outside the creek’s main channel, without portaging. “We’d look at that and scratch our heads and say, ‘Well, I believe you, but I cannot envision what you’re talking about,’” Hames said.

The creek puzzled scientists like Hames because it moved through an unusually wide and flat floodplain where canoeing seemed impossible. Scientists spent 15 years researching the geologic, hydrologic and cultural history of the creek and the surrounding areas. In one area, Hames pulled preserved beaver-chewed sticks out of the mud below the ash layer from Mount Mazama, which erupted 7,700 years ago, creating Crater Lake. “A lightbulb went off,” he said. He suddenly understood, from a Western science perspective, what tribal elders had been saying all along. Extensive beaver dams raised water levels along Toppenish Creek, creating an abundance of wetlands and wapato.

To restore Xapnish, workers breached levees along the creek so water could move across the floodplain. They created basalt structures that functioned like beaver dams, raising water levels. As the tribe purchased more land in the 1990s and 2000s, they also secured associated water rights. Rather than using the creek for irrigation, they used their right for instream flow and acquired nearly all the irrigation rights along the creek. “That’s when you can really rock-and-roll and start doing some stuff,” Hames said.

After the levees were breached, nonnative cattails sprouted. To remove them, the tribe dried up the wetlands by closing a water gate, among other methods, mimicking how water would naturally dwindle by late summer. For two years, they performed what Hames called a “cut and flood” method. They mowed cattails to their stalks, burned them, and inundated the area. Water seeped into the freshly cut plants, killing them. “Then all the good native stuff started coming up,” Hames said.

A photo taken in 1995 after the property was purchased shows a sparse streambank. By 2006, willows grew so thickly that the creek was no longer visible. Tall green tule beds replaced rows of golden grains. Soon after, tribal members began harvesting the tules. Beavers, swans and wood ducks — a biodiverse wetland — also returned.

Hames worked with the Yakama Nation for 22 years to restore thousands of acres. The strategy was simple: Bring back the water, control the weeds, and see what happens. “Never once did I ever plant a wetland plant in any of our projects,” said Hames, who is now the executive director of the nonprofit Wisconsin Wetlands Association. The results were surprising and yet expected, a testament to the tribe’s expertise. Many wetland restoration projects lack such intimate place knowledge. They’ll get a site wet without considering how water originally flowed across the landscape. Such projects often end in weeds, Hames said. Project managers plant native seeds, garden it for five years, check their boxes and leave.

The Yakama Nation continues to manage water levels at Xapnish, burning the site and mowing to control invasives, Elliott said. It’s a relationship to be maintained in perpetuity. “I don’t think anything is ever done in this landscape,” he said.

SOON AFTER WAPATO RETURNED, Washines brought her infant daughter to Xapnish so she could see the plant, smell the rushes and the mud and start to form memories around it.

One of Washines’ earliest memories is of sitting at a ceremonial table where traditional foods were served. She was 4, her chin barely above the table, as she listened to her grandmother speak of their responsibility to care for the foods. Then food was placed on the table.

First came water. Then fish, deer, roots and berries. Then water again.

“If you don’t have the water, the other food isn’t going to be able to follow,” Washines said.

SAND DUNES

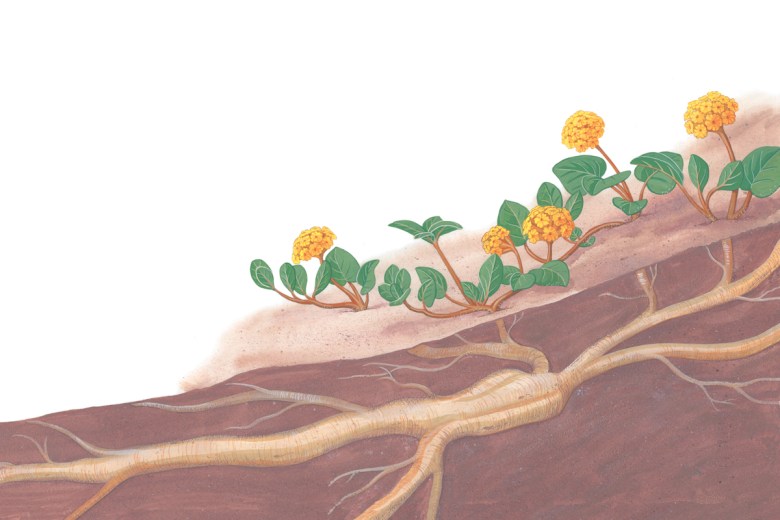

Round succulent leaves of yellow sand verbena, sticky and speckled with sand, stretched across the beach. The stems creep over and below the sand, creating mounds that are six feet across. In spring, canary-yellow flowers bloom in spherical clusters and color the beige dune landscape along the central Oregon coast. The small flowers smell sweet, yet spicy. In the Hanis and Miluk languages of Coos Bay, the plant is called tłǝmqá’yawa, “the scented one.”

Yellow sand verbena is a culturally important plant and traditional food for Indigenous people along the Northwest Coast, including the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, whose unceded lands make up Oregon’s south-central coast and coastal forests. Tribal members harvested the plants’ edible taproot that’s so thick it resembles an African baobab’s tree trunk.

Dune plants like sand verbena thrive in the harsh, salty, wind-blown environment. Some need moving sand to grow and spread their seeds enclosed in winged fruits. Like alpine vegetation, plants here are small but stout, able to survive being blasted by sand, inundated by water, exposed to intense sunlight, or rained on for days. It’s a dynamic system that aggravated white settlers. Sand regularly buried their roads and houses. “The drifting of the sand could certainly be stopped,” a U.S. Forest Service silviculturist wrote in 1910. The agency aggressively planted European beachgrass to stabilize the dunes. The tall grass formed deep rhizomes that hold sand in place, creating a 25- to 35-foot-tall sand wall parallel to the ocean, covered in golden grass. Yellow sand verbena’s edible roots and yellow flowers were replaced by grass monocultures and houses. Their sharp fragrance that once mixed with the salty spring air disappeared. Tribal harvests became memories, notes in old ethnographic journals.

“There’s a relationship that has been broken. So until that relationship is rekindled, hopefully those seeds will last, and those plants will be able to come back.”

By the 1980s, beachgrass took over the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, managed by the Forest Service. From Florence to Coos Bay, the dunes extend 40 miles as North America’s largest expanse of coastal sand dunes. Now, grass and trees are expected to overtake some areas entirely, possibly within 10 to 30 years. Not only have native plants been displaced, but also Western snowy plovers, a federally threatened shorebird who nests on the sandy beaches.

Several years ago, though, yellow sand verbena returned, unexpectedly. After the Forest Service removed beachgrass with bulldozers and herbicide, a handful of plants emerged. They’re abundant in a recently cleared half-mile section of beach near Florence. Beach evening primrose has reappeared, too. Their low-growing, fuzzy, firm leaves spread across the sand in rosettes where thick runners rope the plants together like mountaineers. Beach strawberry, seashore lupine, beach silvertop and beach morning glory have also returned. The bulldozing likely stirred up seeds buried several feet, possibly preserved for decades, though some seeds may have arrived on the wind.

Researchers hope to grow these rare dune plants to create a seed supply for Oregon coast restoration. Non-Native scientists are reluctant to trust what’s growing in front of them. Such an acknowledgment requires a shift in expectation, a letting go of the urge to create instant “old-growth” ecosystems packed full of plants from a pre-colonization past.

Already, the restoration has reawakened a relationship between people and the dunes, said Ashley Russell, assistant director of culture and natural resources for the Confederated Tribes. Plants co-evolved with the tribe through regular harvests. Under pre-colonial tribal management, sand moved freely. “There’s a relationship that has been broken,” she said. “So until that relationship is rekindled, hopefully those seeds will last, and those plants will be able to come back.”

STARTING IN 1992, a group of volunteers spent six years pulling beach grass at the Lanphere Dunes, now part of Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge near Eureka in Northern California. By 2001, hummocks of pink, purple and yellow flowers dotted open mounds of sand, a dune garden. Yellow sand verbena was one of the first plants to return. In other dune restoration projects, plants have recovered on their own.

Without a native seed source for dune plants in Oregon, the Forest Service has been forced to step back and observe.

Time might be just what the plants need. They’ve reawakened with the moving sand and now expect it, Russell said. They’ve returned after fire, when levees are breached, once crops are removed and weeds are killed. They were pushed out for a while but never forgot their home.

Like human relationships, connections between plants and people require nurturing, an element of trust that things can work out.

If plants have responded, then we should listen.

Josephine Woolington is a writer and musician based in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. She is the author of Where We Call Home: Lands, Seas, and Skies of the Pacific Northwest.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the March 2024 print edition of the magazine with the headline “Regeneration Underground.”