Editor’s note: Since this story published, two pending inland port projects, the UIPA Grantsville Proposed Project Area and the UIPA Tooele County Proposed Project Area, were approved by the Utah Inland Port Authority. Upon approval, the areas were renamed Twenty Wells Project Area and Tooele Valley Project Area, respectively.

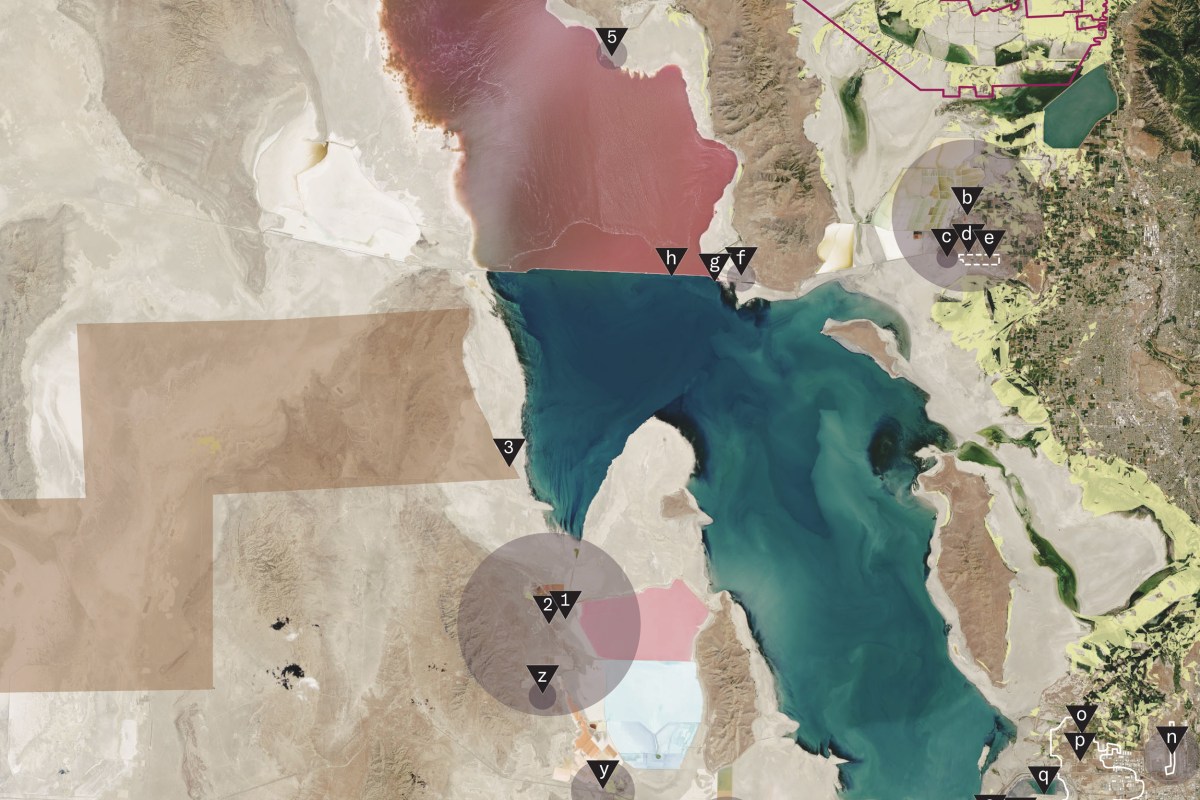

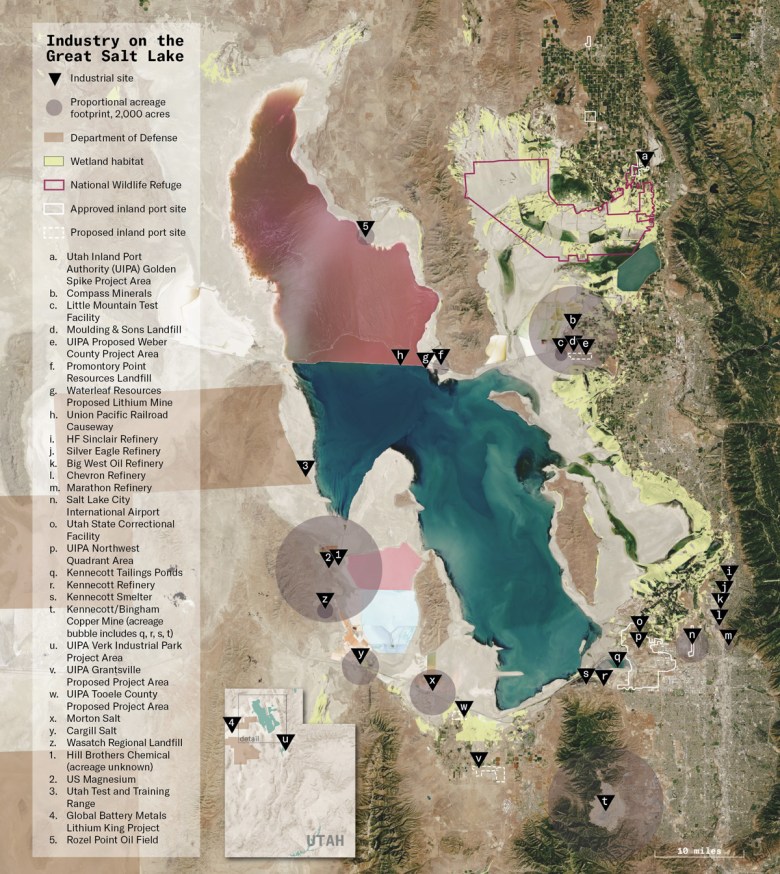

Flying above the Great Salt Lake, you’ll see a patchwork of colors. Evaporation ponds for potash production glow neon-green and fuchsia. The lake’s North Arm, separated from freshwater instream flows by a railroad causeway, radiates a bright pink from microorganisms that survive high salinity. The south half is a deep blue, punctuated by red streaks from brine shrimp cysts, which 21 companies harvest. Often there’s a brownish-gray smog, caused by emissions from magnesium producers and oil refineries or toxic dust clouds from the dried-up lakebed.

The peculiar colors of Utah’s inland sea — the largest saline lake in the Western Hemisphere — are largely from industrial development. After all, “the state’s motto is ‘industry,’” said Chandler Rosenberg, deputy director of the Great Basin Water Network. Mormon settlers dubbed Utah the Beehive State because bees symbolized hard work. Despite scientists’ warnings that drought and unsustainable water use could make the lake disappear in five years, extraction and pollution continue. On Sept. 6, five environmental groups, including the Utah Rivers Council and the Center for Biological Diversity, sued Utah for failing to protect the Great Salt Lake. If they win, Utah may have to reconsider its motto.

A tour around the lake reveals what environmentalists are up against: the cumulative impacts of more than a century of unchecked development.

Despite scientists’ warnings that drought and unsustainable water use could make the lake disappear in five years, extraction and pollution continue.

Starting on the west edge just below the railroad causeway that divides the lake in two, the U.S. Air Force practices bombing and gunnery at the Utah Test and Training Range, the largest special-use airspace in the continental U.S. and a hazardous waste storage site that has contaminated groundwater.

Nearby, on the lake’s North Arm, is the site of Waterleaf Resources’ proposed lithium mine. The lake’s brine contains lithium, and new prospectors and longtime local companies are eager to cash in on the battery metals boom. Earlier this year, the state updated its lithium-mining royalty standards, which include new water conservation measures for the lake, but it’s unclear when they’ll go into effect. In July, Waterleaf Resources submitted an application to the Utah Division of Water Rights for 225,000 acre-feet of water from the lake, claiming they’ll return it all once the lithium is removed.

Farther east beyond the causeway, avocets, pelicans, phalaropes and over 200 other bird species nest and feast at the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge on their journey between Canada and South America. In August, the Utah Inland Port Authority (UIPA), a state agency, approved a new project area a half-mile away. As of mid-November, UIPA has three approved and three pending inland port projects — manufacturing, transportation and warehouse logistics centers — on or near the lake’s wetlands. Meanwhile, the Utah Legislature established a water trust in January 2023 that includes $10 million for wetland protection. Ben Abbott, an ecologist at Brigham Young University, called the lake, which provides critical habitat for millions of migratory birds along the Pacific Flyway, “the center of wetland conservation, not only for Utah, but the Western U.S.”

Southwest of the refuge, technicolor evaporation ponds have produced potash for fertilizer for nearly 60 years. Last year, Compass Minerals announced plans to mine lithium from the ponds but has since put those aspirations on hold as the state finalizes its new mining regulations.

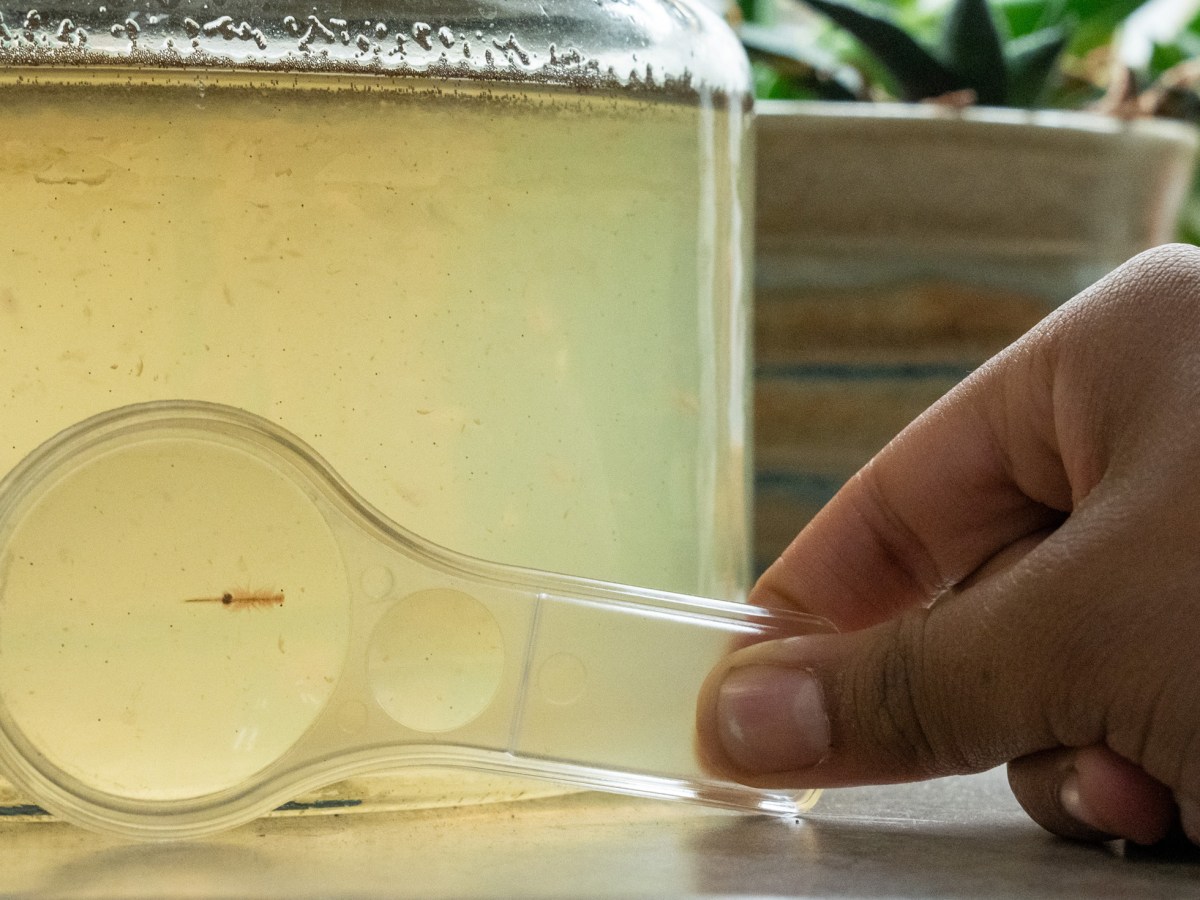

A short distance away is a landfill. South toward Salt Lake City, you can see Antelope Island, the site of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation’s creation story. On the city’s west edge, oil refineries disproportionately pollute communities of color. At the southeastern corner, the new Utah state prison abuts sensitive wetlands, where corrections staff apply larvicide to control the mosquitoes that swarm incarcerated people. Farther along warehouses and semi-trucks fill UIPA’s first inland port site. A 2016 Market Assessment by the University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute found that prison infrastructure made building the port easier. “In many ways,” the report said, “the development of a prison and inland port are complementary.”

Farther down the south shore, tailing ponds and the smelter of Bingham Canyon Mine, one of the world’s largest open-pit mines that’s been producing copper since 1903, rise behind the Great Salt Lake State Marina where crew teams and sailors recreate. At the lake’s southwestern edge, the Bonneville Salt Flats, a famous speedway and recreation area managed by the Bureau of Land Management, glitter next to a Morton Salt plant.

“At what point do we draw the line with extraction? Especially at Great Salt Lake when our public health is at stake, and the health of the lake is like hanging on by a thread.”

Completing the tour, a smokestack emits chlorine gas from U.S. Magnesium, which causes 10-25% of northern Utah’s air pollution, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The plant also illegally disposed of highly acidic hazardous waste for years, and the resulting Superfund site’s cleanup plan relies on pumping water from the Great Salt Lake and letting it evaporate, leaving a foot-deep salt cap on top of the waste ponds. Last year, the Utah Department of Environmental Quality denied U.S. Magnesium a permit to dredge further into the lake. The plant is North America’s largest producer of primary magnesium, which it removes from the lake’s salt water. The company also hopes to profit from the lithium demand; it already has an agreement with the state to extract the soft, white battery metal from its waste ponds.

“At what point do we draw the line with extraction?” Rosenberg said. “Especially at Great Salt Lake when our public health is at stake, and the health of the lake is like hanging on by a thread.”

Rosenberg senses a shift in Utah’s relationship to industry, noting the more restrictive mineral policies passed earlier this year, the unexpected denial of US Magnesium’s dredging permit and rising public concern. “I think as awareness of the crisis at Great Salt Lake has become widespread,” she said, “people are really tuned into the fact that we can’t allow further exploitation on the lake.”

Brooke Larsen is the Virginia Spencer Davis Fellow for HCN, covering rural communities, agriculture and conservation. She reports from Salt Lake City, Utah. Email her at brooke.larsen@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy. Follow her on Instagram @jbrookelarsen or Twitter @JBrookeLarsen.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline A toxic tour of the Great Salt Lake.