Zaj dab neeg no muab txhais ua lus hmoob nyob rau nov thiab.

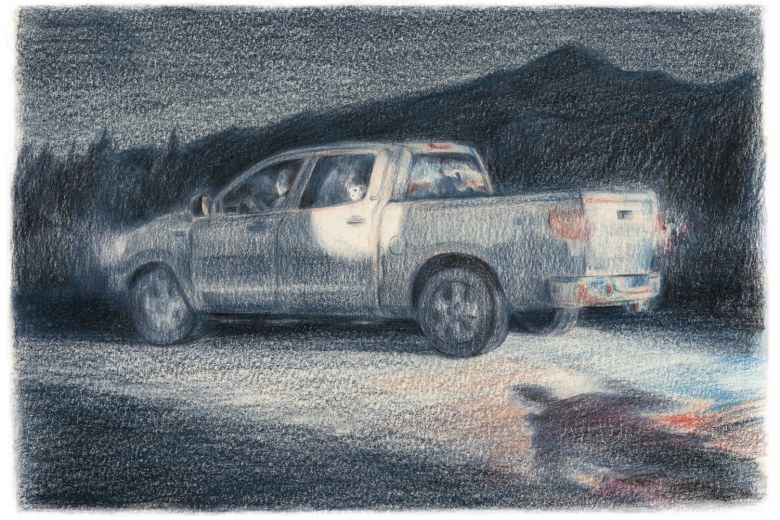

Driving down a California highway one night last June, Mai Yang noticed lights tailing her. Yang, a former worker at a medical device factory and the mother of three school-age children, suspected that it was someone from the Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Department. Others in the area’s Hmong community said that they were being pulled over often, especially here, near the lone stop sign where Northern California’s U.S. Route 97 meets Highway A12.

Yang concentrated and stayed calm, carefully bringing her Toyota Highlander to a complete stop before she made a right turn. Still, red and blue lights flashed in her rearview mirror. What did I do wrong? she wondered as a law enforcement officer approached with a flashlight. She tried to reassure herself: I’m safe; I stopped completely.

The flashlight’s beam moved around her truck bed, jumped onto her backseat through the side windows and finally into the front where she sat. “You know, you need to come to a complete stop at the sign,” Yang recalled the officer saying. She knew that she had, but didn’t argue. “Yes, sir,” she replied. The officer then left. The interaction had lasted just a few minutes, and during that time, Yang said, he did not run her license or take down her information. It was unlike any traffic stop Yang had ever experienced.

A week later, as she was returning from the grocery store with her family, Yang said she was pulled over again — at the same intersection and by the same officer, though he didn’t seem to remember their previous encounter. This time, the flashlight caught her son’s face in the backseat, next to a pile of groceries and Yang’s mother.

Less than a week later, she said that it happened a third time. She was alone, and this time, she offered her ID to him. But he declined to take it.

There are no records that match the time, date, name, or location of any of the stops that Yang describes in Siskiyou County’s database, including its in its “Computer Aided Dispatch System,” which is supposed to document basic details of law enforcement interactions. High Country News reviewed these records.

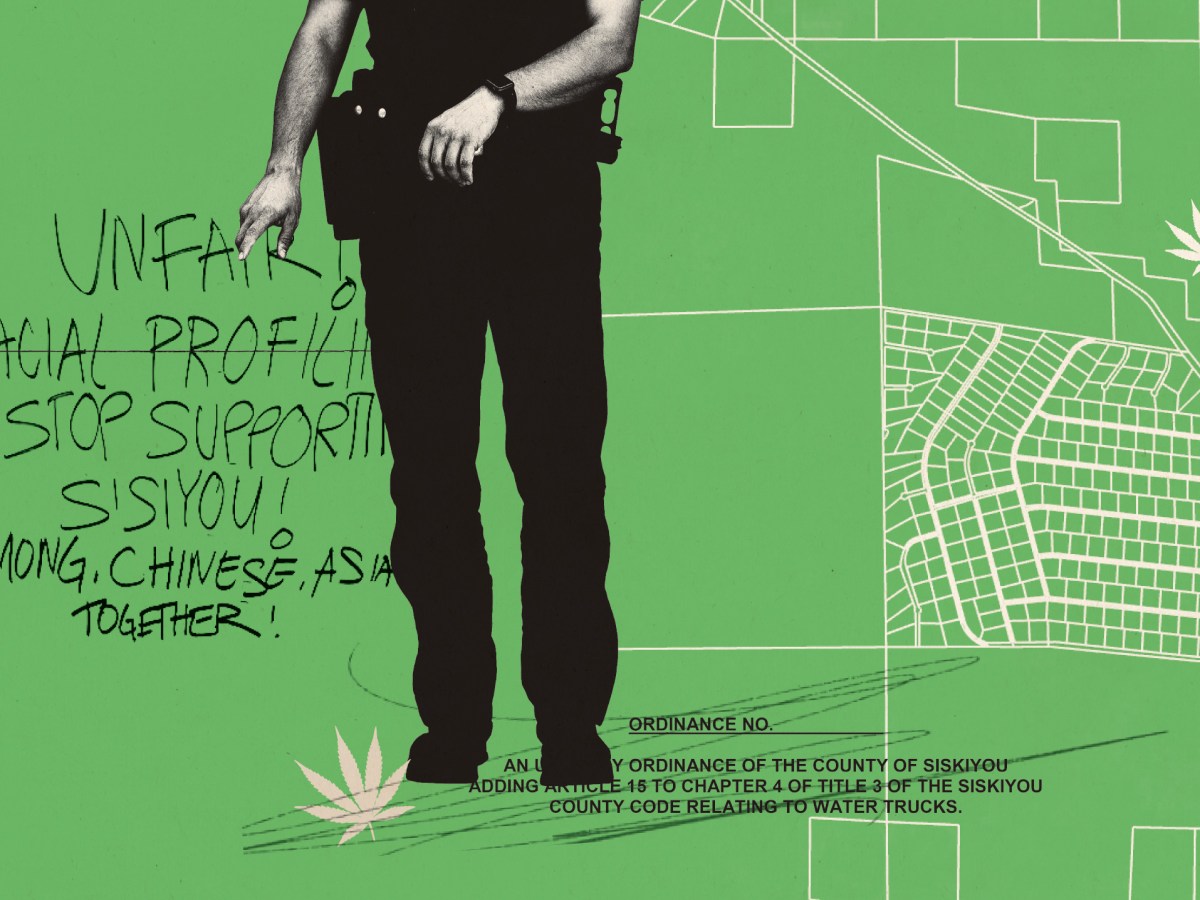

Under California’s Racial and Identity Profiling Act (RIPA), police departments must also report information about stops, including the driver’s perceived race, to a state oversight board. But reports — when they happen — are not always accurate. A 2022 study found widespread underreporting of Hispanic drivers by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, while the LA Police Department inaccurately recorded data in nearly 40% of incidents, according to a 2020 audit.

Cha Vang, a member of the California Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board, told HCN that it lacks the legal authority to mandate reporting standards or force law enforcement departments to improve their practices. It can only make recommendations. Vang called it “a faulty system.”

“After RIPA passed,” she said, “elected officials are not interested in pushing the policies we are asking them to.”

TO YANG, and other members of Siskiyou County’s relatively large Hmong population, the traffic stops are part of a years-long pattern of racial profiling by law enforcement. In September, sitting on the front porch of a small community center in Mt. Shasta Vista, Yang claimed that her husband had recently been pulled over at the same stop sign, as had her sister-in-law. “Anything can happen,” Yang said. “You never know. For me and my husband, we are both scared. The cops are comfortable to do anything they want to. No one can stop them.”

In 10 interviews last summer, Asian residents described repeated targeting and harassment by police in Siskiyou County. The American Civil Liberties Union and the Asian Law Caucus filed suit against the county and the sheriff’s department in 2022 over these allegations. The parties are currently in settlement negotiations.

A court order that required the department to report all traffic stops under RIPA expired on Dec. 31, 2023 — something the department claims to have been doing all along. The ACLU’s complaint alleges that Asian drivers in the county were stopped at a rate 12 times greater than their share of the population. The sheriff’s office said it is targeting drug trafficking, but, according to the complaint, only a small proportion of stops resulted in the seizure of illicit drugs.

Stops like the ones Yang and her family allegedly experienced, where a police officer stops a civilian for a minor or nonexistent offense, apparently in hope of finding evidence of a more serious crime, have long been legally challenged for violating drivers’ constitutional civil rights. In California, there are ongoing efforts to fight this practice, including with statewide legislation. But decades of court decisions have diluted the protection drivers have against unreasonable searches and seizures, making it easy for police officers to justify most stops.

“You never know. For me and my husband, we are both scared. The cops are comfortable to do anything they want to. No one can stop them.”

HMONG AMERICAN and other Asian American people started moving to Siskiyou County in the mid-2010s, settling in rural subdivisions. Many of the Hmong immigrants are veterans of and refugees from the CIA’s “secret” war in Laos in the early 1970s. Families bought land, built homes and started businesses, like grocery stores and restaurants. In the subdivisions, people grew medical cannabis alongside other farm crops and animals. As is common in the region, some people started larger farms and sold the crop commercially — albeit illicitly. Cannabis provided a decent livelihood in a place with few job opportunities.

Around the same time many of the Hmong people arrived, the Siskiyou County Board of Supervisors passed a complete prohibition on nearly all cannabis cultivation. (Cannabis is legal in California, but counties can outlaw its cultivation within their boundaries.) Despite the ban, commercial cannabis boomed, as did the size and number of the farms that produced it. Lacking any system to manage the industry, the county implemented hardline law enforcement tactics, focusing particularly on the growing number of Hmong and Chinese farmers.

According to emails obtained by HCN and records of public meetings, racial animosity was a common factor in the police crackdown, with search warrants, raids and drone surveillance. There were lawsuits to shut down wells and property liens aimed at taking over land titles in areas where Hmong and Chinese people owned land. In 2021, an attempt to cut the area’s water supply was halted in federal court over complaints that it targeted Asian Americans; the case was settled two years later, and the laws were repealed.

In the emails obtained by HCN, department officials seemed aware that their tactics could bring allegations of violating the law, in part because those tactics were apparently impacting “Hmungs (sic) and Chinese marijuana growers,” as one deputy put it.

“The task which we are asking of you,” wrote Undersheriff James Randall, the department’s second-in-command, in a 2021 email to the traffic stop team, “will put each and every one of you on the front lines of any potential complaint and in the spotlight for accusations of civil rights violations or racial profiling.” Randall instructed them to “do their job” within policy and case law, while “pushing that envelope to the edge in order to remind the drug trafficking organization that we are here. … The department and the county … are all behind you and in full support of you while you combat this issue.

“Do not let any rumors or information regarding involvement of attorneys or the ACLU slow you down or deter you in any way,” Randall continued. “As long as you are acting within your lawful scope, they cannot touch you.”

In 2022, Sheriff Jeremiah Larue explored the possibility of raising criminal penalties for cannabis-related offenses from misdemeanors to felonies, as HCN previously reported. The emails obtained by HCN appear to show the district attorney, Martha Aker, trying to identify cases that might qualify for felony charges. “I think that the Hmongs will care about felony charges,” Aker said in an email to the sheriff’s office, “so this should help.”

Reached for comment, LaRue said that, owing to a “pending legal matter,” the department was unable to respond to a detailed list of questions. But he did say, “I’m not aware of any improper actions taken by deputies in enforcing the law. If such complaints come forward, we will investigate.”

Even after the ACLU lawsuit was filed, many members of the Hmong community told HCN they were stopped frequently during the summer and fall of 2023 and into early winter. April Lee, a community organizer in Shasta Vista, said she received multiple calls from scared older residents. Some were crying, saying that their car had just been searched. Others had started buying American cars — Ford instead of Toyota — hoping to shield themselves from profiling. “We’ve had cops going back and forth like crazy, stopping people for no reason, telling you to fix your light in broad daylight. We’d never seen that before,” Lee said. “It’s scary, especially for our elders.”

“It’s scary, especially for our elders.”

RESEARCH SUGGESTS that “enforcement first” approaches to regulating cannabis, like Siskiyou County’s apparent approach, don’t actually work; they merely fuel racial tension and complicate attempts to regulate groundwater and enforce environmental and labor standards. Margiana Petersen-Rockney, a post-doctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, has published three peer-reviewed papers and three policy reports on Siskiyou County. Her team’s findings were somewhat counterintuitive, she told HCN: In punishment-oriented counties, she said, illicit farms are generally bigger than those in more lenient counties. For farmers in such a risky climate, scale becomes a business strategy: You go big mainly in order to hedge your business against the likelihood of raids.

The more successful counties opted for a softer approach, educating and encouraging best practices among small farmers and local communities and using their limited resources to crack down on bad actors.

“In places like Siskiyou County, most people want to do the right thing,” Petersen-Rockney said. But punishment just pushes the growers further underground, “further from the reach of regulation, onto more sensitive land, and into more extractive practices socially and environmentally.”

The alleged targeting of Hmong and other Asian drivers has fostered a deep distrust, deepening the already fraught racial tensions in the majority-white area. April Lee, the community organizer, said that at the very least, she wants her community to be able to drive without fear.

“I hope that they can do it according to the law,” said Lee. “I love this place; our old people love to be here. They get to live how they lived back home. Everyone wishes we could be in one community.”

This story has been updated to correct the expiration date of the court order requiring Siskiyou County to report all traffic stops.

Theo Whitcomb is a writer and filmmaker living in Oregon. Formerly, he was an editorial intern at High Country News. Follow him on Twitter @theo_whitcomb.