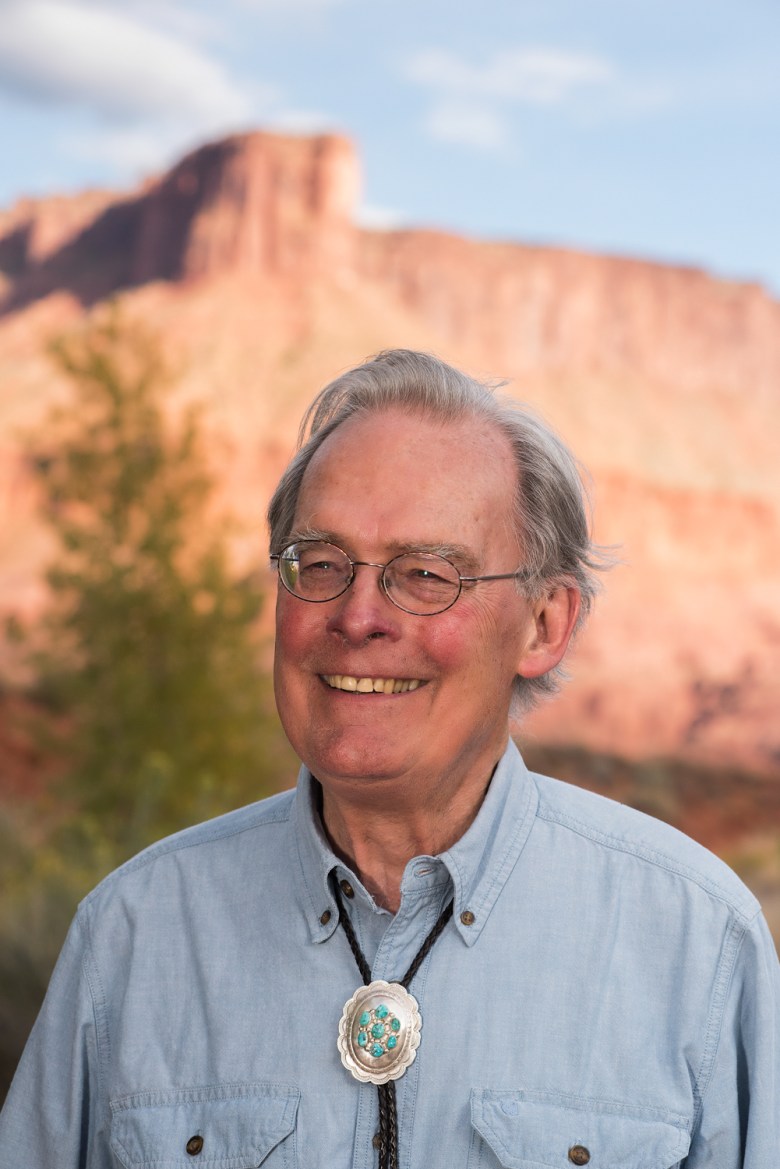

On Sept. 23, we will gather in Boulder, Colorado, to honor the life of our friend Charles Wilkinson, who returned to the spirit world on June 6, 2023. Charles was and is well-known as a professor of law and a leader in natural resources and public-lands issues, as well as in the field of federal Indian law. As an accomplished author and scholar, his work reflected his deep love of Western lands and his admiration of tribal nations, exemplifying his strong belief that the two can and should prosper in harmony. As an advocate, he championed and implemented ideas on how this harmony could be achieved.

Charles believed tribal sovereignty was one of the “noblest ideals,” something that touched his mind and lived in his heart. Working with his close friends John Echohawk (Pawnee) and the late David Getches at the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), Charles fought for the rights of tribal nations, earning significant victories across the United States. He built from those early cases throughout his career, devoting special attention to Pacific Northwest salmon and the Colorado Plateau. Billy Frank Jr., the late Nisqually leader, was a close friend — “Goddammit, Charles, we’re taking over!” he’d often say — and the subject of Charles’ book, Messages From Frank’s Landing, while the seminal 1974 U.S. v. Washington tribal treaty fishing rights case known as the Boldt decision, was the focus of his final book. To Charles, the Boldt decision was as important and compelling as Brown vs. Board of Education, another case where civil rights and justice prevailed, altering the course of a disenfranchised people and changing society for the better. The Boldt decision had the same impact on Indigenous peoples who were being unlawfully prohibited from exercising their treaty fishing rights — rights that are critical to their cultural and physical well-being. He completed the book just a few days before he passed away.

Charles was more than a brilliant lawyer, dedicated professor and gifted author; he was a true friend to Indian Country. To him, the field of federal Indian law was not just an interesting intellectual or professional pursuit; rather, it was a testament to the perseverance of a people. He saw that Indigenous people achieved the revival of tribal nations through their own vision, determination and action, not because of the federal government or anyone else. When he spoke to Indigenous audiences, as he often did, on tribal and natural resource issues, he reaffirmed this belief, answering questions as seriously as if the Interior secretary was asking them: thoroughly, and with deep respect. It was not uncommon for him to use his platform to encourage Indigenous people to believe in their cultures and advocate for them. Charles’ work on Indigenous issues was never about him; it was always about doing all he could to support justice for Indigenous people.

Charles’ work on Indigenous issues was always about doing all he could to support justice for Indigenous people.

Charles leaves behind a legacy in Indigenous advocacy that we and others will spend our lives trying to fulfill. He demonstrated an abiding belief in the next generation, a willingness to train future lawyers and leaders, and an eagerness to pass the torch to new generations. He embraced the traditional qualities of Indigenous cultures along with our newer ideas about advocacy, listening with excitement as we talked about tearing down dams to bring salmon back or discussed land-management planning at Bears Ears National Monument and going to the United Nations for human rights diplomacy. Those conversations in the NARF living room, in his office, on somebody’s front porch, or under an old apple tree filled us with strength and purpose and the knowledge that it was our responsibility to develop our own wisdom and nurture those who will follow us.

Charles often followed up a meeting or an event with a handwritten note, scrawled in his blue felt-tipped pen, capturing the emotion of the moment. Eventually, he turned to email and even got a cellphone. He would sign off with “all my best spirits.” That’s how we will always remember Charles Wilkinson, with all our best spirits, and with our lasting gratitude.

Daniel Cordalis, Diné, is an attorney working on Indigenous and natural resource issues and a former research assistant of Charles Wilkinson.

Kristen Carpenter is the Council Tree Professor of Law, Director of the Indian Law Program, and former colleague of Charles Wilkinson at the University of Colorado School of Law.

Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.