This is an installment of the Landline, a fortnightly newsletter from High Country News about land, water, wildlife, climate and conservation in the Western United States. Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Earlier this month, an op-ed by Bureau of Land Management Director Tracy Stone-Manning appeared in local and regional news outlets across the West. In it, she explained that her agency works to balance various uses — from energy and mining to grazing and recreation — but that climate change is making everything more difficult. “Fortunately,” she writes, “there is one way to ensure our public lands will provide the countless resources they always have: prioritizing landscape health.”

Even as folks perused her words on their laptops, the Biden administration was taking action on this front, with a flurry of recent land-policy decisions. In some cases, however, the administration fell short of the ideals Stone-Manning laid out. When it comes to the well-being of federally managed public lands, the past month has been a mixed bag.

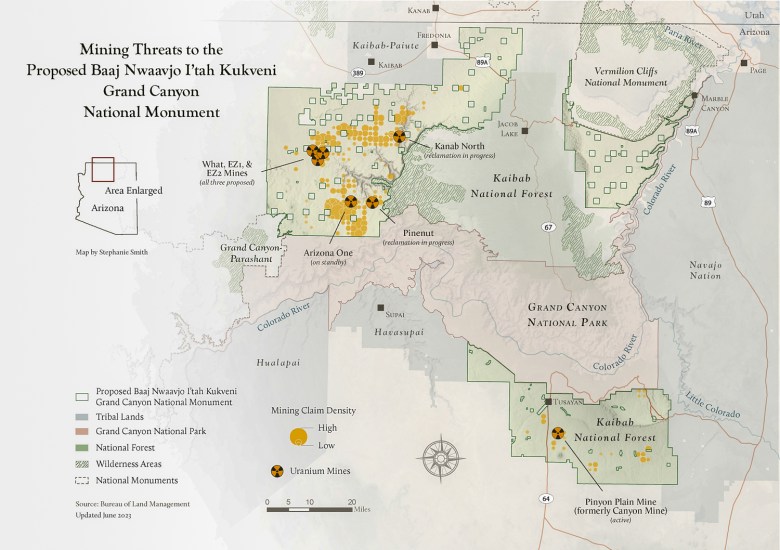

On Aug. 8, President Joe Biden stood before Red Butte, a prominent landform on the Coconino Plateau in Arizona just south of the Grand Canyon, and designated a new national monument — Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni-Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon. Biden extended protections to 917,000 acres on three distinct swaths of public land straddling the canyon at the behest of the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, which represents 13 tribal nations in the region.

The boundaries closely follow those of a 20-year ban on new mining claims that the Obama administration established in 2012. The national monument will permanently withdraw these federal lands from new mining claims, though won’t affect valid — meaning legally binding — existing mining claims and permits, including Energy Fuels’ currently idled Pinyon Plain uranium mine. Indigenous and environmental advocates have long attempted to block operations at this facility, citing its potential to contaminate groundwater and otherwise harm ecosystems near the Grand Canyon.

The future of the hundreds of additional existing mining claims on parcels of land scattered across the new national monument is less clear, however. While the claims are considered “active” by the Bureau of Land Management — meaning that the claimants’ paperwork is up to date — their “validity” depends upon the claimant’s ability to demonstrate the presence of valuable and mineable minerals — a time-consuming and expensive process.

HCN’s Brooke Larsen and Alastair Lee Bitsóí give a good rundown of the monument designation and the Indigenous advocacy that led to it. Also, check out this beautiful photo essay by Len Necefer.

THE VALIDITY, or lack thereof, of an existing mining claim within a national monument was one of the issues behind the Utah lawsuit that sought to overturn Biden’s restoration of the original boundaries of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments. We’ll get to that in a second, but first, the news: That lawsuit was tossed out by District Judge David Nuffer, who found that the Antiquities Act gives the president broad authority to designate national monuments, and that it is up to Congress — not the courts — to review or limit that authority.

One of the plaintiffs in that suit was Kyle Kimmerle. In 2018, his family mining company staked several claims in formerly protected areas that removed from Bears Ears National Monument by the Trump administration in 2017. Biden restored the monument’s original boundaries in 2021, including the parcels that Kimmerle had claimed. Kimmerle filed for a permit to work some of those claims anyway, arguing that since they were active and existed prior to the boundary restoration, his right to mine remained. But the BLM wasn’t buying it. Yes, the agency agreed, those claims are active, but Kimmerle would still have to demonstrate they were valid before he could receive a permit.

Instead of forking out at least $90,000 for a mineral examination that might turn up nothing, Kimmerle joined Utah’s lawsuit, claiming that the permit denial deprived him of his legal rights. Zeb Dalton, a public-lands livestock operator, also intervened in the suit, wielding similar claims.

In a previous Landline, we wrote about the flimsiness of the Beehive State’s suit, which baselessly argued that the national monuments were just too darn big and that while a few arbitrarily chosen landforms might be worthy of protection, thousands of others were not.

But it wasn’t the glaring logical flaws in the plaintiffs’ arguments that got the case thrown out; it was also legally unsound. Judge Nuffer found that the monument proclamations were not subject to judicial review, because that requires Congress to waive the federal government’s sovereign immunity, which Congress hasn’t done. He further found that BLM guidance memos — which the plaintiffs claimed hampered their livelihoods — were not final agency actions, and therefore not subject to judicial review.

Utah is appealing the decision. In the meantime, the national monuments will stand, and the agencies and tribal nations tasked with stewarding them can continue to work on creating their management plans.

THAT WORK IS nearing completion for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. The Interior Department recently released the draft resource management plan and environmental impact statement for the restored monument and is seeking public input on four possible alternatives.

A national monument’s management plan is always a big deal, because it determines what level of protection the monument will get. Currently, a Trump-era plan governs the monument in southern Utah, offering little in the way of extra protections. Even before that, the agencies overseeing Grand Staircase-Escalante were criticized for failing to adequately staff, fund and protect the 1.9 million-acre monument and allowing too much grazing and off-highway vehicle use.

So it’s nice to see that the feds’ preferred plan — aka Alternative C — is a big improvement on the status quo, since it “emphasizes the protection and maintenance of intact and resilient landscapes using an area management approach.” Though it offers fewer protections than Alternative D, it would significantly increase limits on grazing, motorized vehicles and target-shooting across the monument.

Contrary to what Utah politicians and sagebrush rebels might say, about 97% of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is still available for livestock grazing, and the number of animals permitted to graze has remained virtually unchanged since the monument’s 1996 establishment.

2.23 million acres

The extent of the area to which the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument management plan will apply. (It also extends onto some neighboring federal lands.)

125,800 acres

Amount of that land that is currently wholly or partially unavailable for livestock grazing.

314,700 acres

Amount of land that would be unavailable for grazing under preferred Alternative C.

In addition to reducing the amount of land open to grazing, the preferred alternative would also permanently retire currently un-permitted grazing allotments and prohibit range “improvements” aimed at increasing livestock forage. Land-health assessments would also be required for permitted allotments.

Scott Berry, president of the Grand Staircase-Escalante Partners board, acknowledges that the preferred plan isn’t perfect, but still sees it as a vast improvement over the existing Trump-era plan, which will remain in effect until the new plan is adopted. “Political forces in Utah are going to do everything in their power to prevent the new plan from being adopted as scheduled,” he warned. To counter that, he went on, the environmental community should weigh in and support the two most protective alternatives.

But first, you should probably dive in and check out the 1,200-page, two-volume draft plan for yourselves. It’s an interesting read.

AS LONG AS we’re talking grazing and landscape health, the group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility has filed a lawsuit against the BLM, accusing the agency of wrongly withholding ecological health assessments for a whopping 155 million acres of public-land grazing allotments. Those assessments are supposed to guide grazing management decisions, and watchdogs and citizens can use them to make sure the agency is doing its job.

Transparency for these assessments is about to get even more important: The BLM’s proposed Public Lands Rule, which aims to put conservation on a par with other uses and give land managers more leeway to enact protective measures, would extend this tool to all public lands, not just grazing allotments.

LAST YEAR, the Biden administration announced that it was getting ready to update public-lands grazing rules in an effort to make federal lands more resilient to climate change and drought. The prospect stirred up a bit of excitement among conservationists, who saw an opportunity to finally increase grazing fees and maybe kick the cattle off sensitive lands and give the range a chance to heal. But there was also a fair amount of skepticism: The livestock industry continues to wield considerable political heft, even as its economic potency wanes. Conservation advocates expected that the beef lobby would try to suppress any effort at true reform.

And it looks like the skeptics were right, at least for now. On July 12, the BLM quietly announced that it is “adjusting its approach to updating the Grazing Rule” and, in the near term, would “shift its focus from advancing a rulemaking” to updating policies administratively. That means the public will have little say in any changes.

THE BLM APPEARS to be implementing some parts of its proposed Public Lands Rule before it’s finalized. The rule makes it easier for land managers to establish areas of critical environmental concern, or ACECs, thereby giving those lands additional protection from drilling and mining — although not necessarily from grazing. The agency’s draft resource management plan for its Rock Springs Field Office in southern Wyoming, which includes the imperiled Red Desert, would establish ACECs on an additional 1.3 million acres. The Casper Star-Tribunereports that Wyoming conservationists generally like the preferred plan, while the petroleum industry called it “frustrating.”

ULTIMATELY, HOWEVER, all the protections in the world don’t mean a whole lot if they aren’t enforced. Just as he has for more than three decades, Cliven Bundy continues to run his cattle illegally on public lands in southern Nevada, where they gnaw on sparse vegetation and trample sensitive soils in desert tortoise habitat. And in Colorado’s San Luis Valley, BLM Range Management Specialist Melissa Shawcroft has recorded 36 grazing trespass incidents in the past year alone. Instead of rounding up the cattle or their owners, however, the agency slapped Shawcroft with a 14-day suspension for “discourteous” behavior after she questioned her bosses’ lack of gumption, once again proving that bullshit is as easy to find in agency offices as it is underneath the hooves of livestock.

Hold the Line: Stories from HCN and elsewhere that are worth your time

In one of the Biden Administration’s more dubious decisions to date, the Surface Transportation Board and the U.S. Forest Service gave the go-ahead to a proposed oil railway in Utah. The line would link the Uinta Basin oil and gas fields to the national rail network, allowing trains to haul the fields’ crude across neighboring states —alongside the Colorado River for some stretches — to Gulf Coast refineries. Colorado communities along the rails weren’t too pleased about the prospect and together with conservation groups sued over the approval. Early this month a federal appeals court ruled in their favor, reports Samuel Shaw for HCN, tossing out the Surface Transportation Board’s approval and ordering the agency to redo its analysis, this time factoring in potential down-rail impacts to the environment and public health and safety. | High Country News

Ed Abbey, thou shouldst be living at this hour: California alfalfa farmers want to join forces with Hayduke & Co. and take down Glen Canyon Dam. Say what?!? Well, maybe we’re sensationalizing things just a bit here. But the fact is that — aside from the Hayduke part — this rather surprising news is true. In comments to the Bureau of Reclamation regarding management of the Colorado River, the Imperial Irrigation District — the river’s largest single water user — urged the agency to prioritize honoring senior water rights over propping up Lake Powell to preserve hydropower capacity. Thing is, Glen Canyon Dam doesn’t really work when the reservoir gets that low. And that leaves just one option. As the irrigators put it in their written comments: “Past proposals by environmental groups to decommission Glen Canyon Dam or to operate the reservoir without power production as a primary goal can no longer be ignored and must be seriously considered. …” To be sure, this decommissioning — if it ever happens — probably would not involve explosive-laden houseboats and a cinematic climax. Most likely it might mean drilling diversion tunnels around the dam, allowing the river to run more or less free without actually breaching the dam. | KLAS

Your news tips, comments, ideas and feedback are appreciated and often shared. Give Jonathan a ring at the Landline, 970-648-4472, or send us an email at landline@hcn.org.

Jonathan Thompson is a contributing editor at High Country News. He is the author of Sagebrush Empire: How a Remote Utah County Became the Battlefront of American Public Lands.