The essential insight of road ecology is this: Roads warp the earth in every way and at every scale, from the polluted soils that line their shoulders to the skies they besmog. They taint rivers, invite poachers, tweak genes. They manipulate life’s fundamental processes: pollination, scavenging, sex, death.

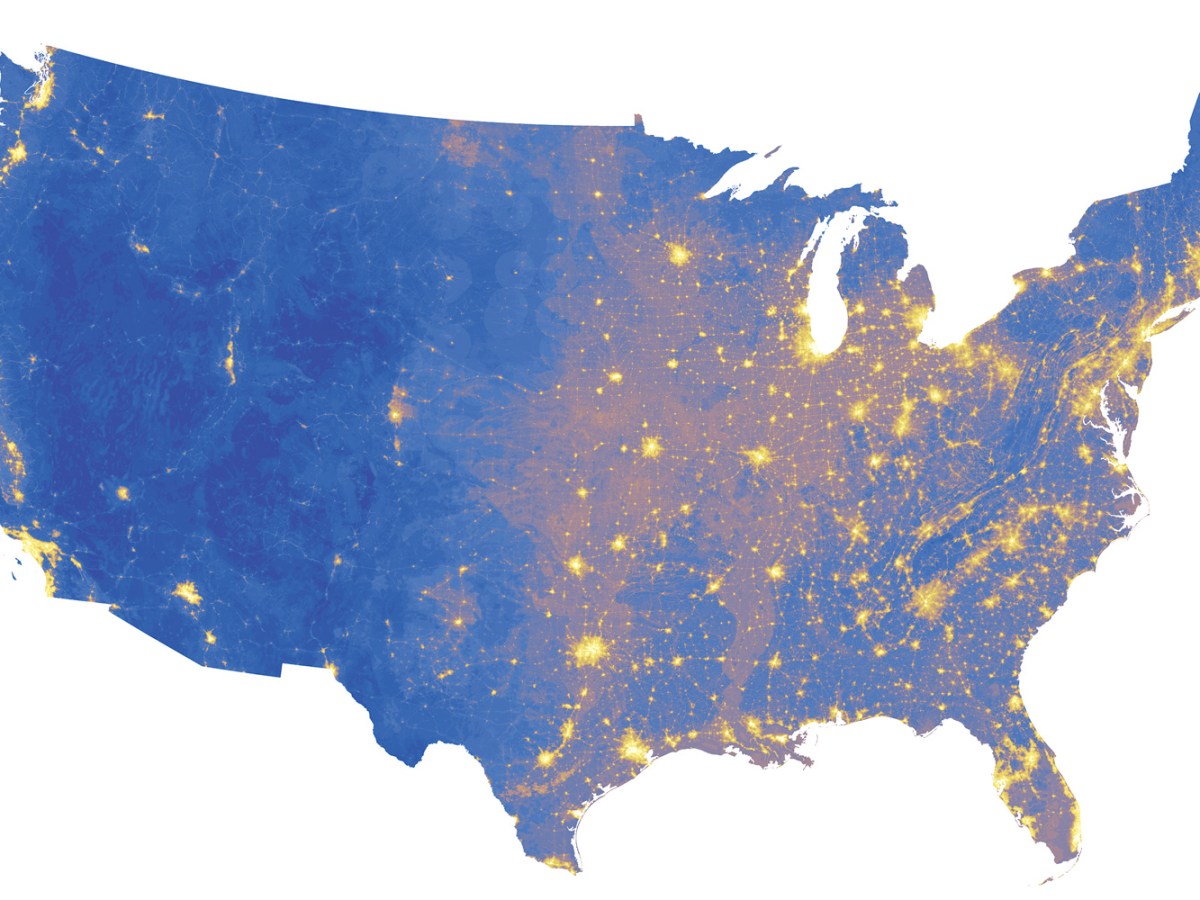

Among all the road’s ecological disasters, though, the most vexing may be noise pollution — the hiss of tires, the grumble of engines, the gasp of air brakes, the blare of horns. Noise bleeds into its surroundings, a toxic plume that drifts from its source like sewage. Unlike roadkill, it billows beyond pavement; unlike the severance of deer migrations, it has no obvious remedy. More than 80% of the United States lies within a kilometer (approximately 0.6 of a mile) of a road, a distance at which cars project 20 decibels and trucks and motorcycles around 40, the equivalent of a humming fridge.

Like most road impacts, noise is an ancient problem. The incessant rumble of Rome’s wagons, griped the poet Juvenal 2,000 years ago, was “sufficient to wake the dead.” To walk in 19th-century New York, Walt Whitman wrote in Song of Myself, was to experience the “blab of the pave,” including the “tires of carts” and “the clank of the shod horses.” As car traffic swelled in the 20th century, road noise became a public-health crisis, interrupting sleep, impairing cognition and triggering the release of stress hormones that lead to high blood pressure, diabetes, heart attacks and strokes. A 2019 report by one French advocacy group calculated that noise pollution shortens the average Parisian life span by 10 months. In the loudest neighborhoods, it truncates lives by more than three years.

To a road ecologist, noise is pernicious precisely because it isn’t confined to cities. Road noise also afflicts national parks and other ostensibly protected areas, many of which have been gutted by roads to accommodate tourists. A vehicle inching along Going-to-the-Sun Road, the byway that wends through Glacier National Park, casts a sonic shadow nearly three miles wide. “Once you notice noise, you can’t ignore it,” conservation biologist Rachel Buxton told me. “You’re out in the wilderness to have this particular type of experience where you escape and relax, and noise ruins it. It totally ruins it.”

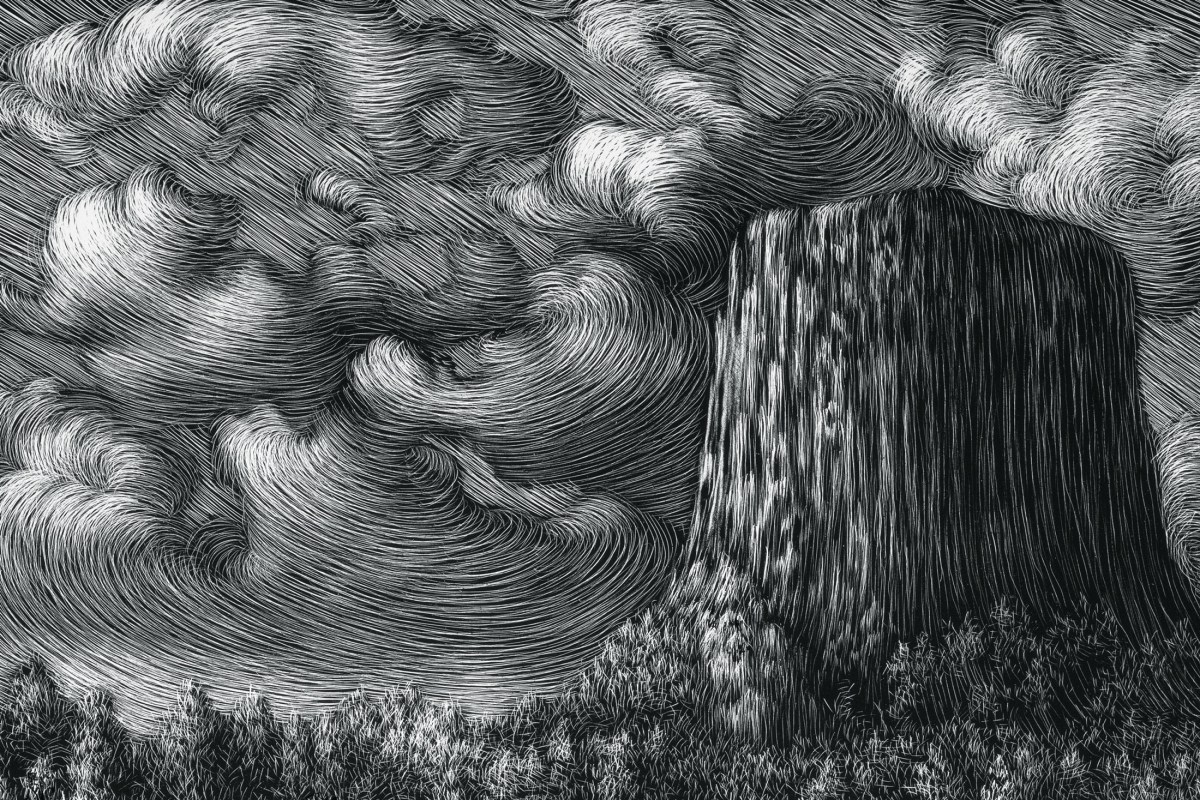

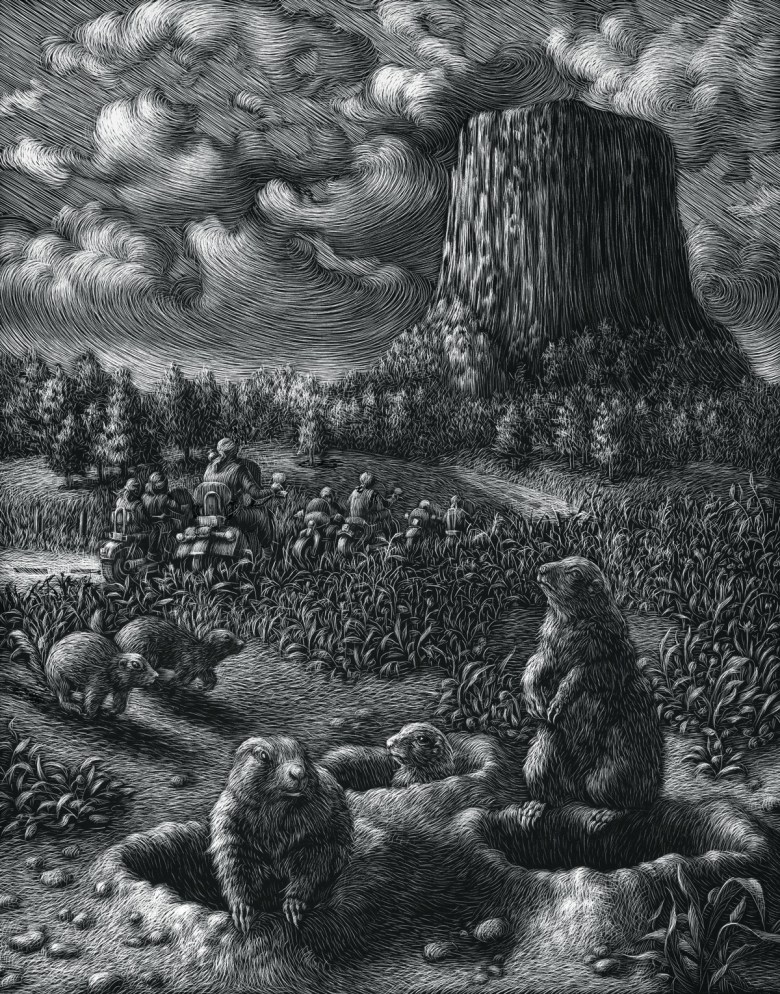

And road noise isn’t merely an irritant; it’s also a form of habitat loss. In Glacier, the distant grind of gears startles mountain goats; in one Iranian wildlife refuge, a highway drives a 40-decibel wedge through a herd of Persian gazelles. The bedlam directly challenges the purpose of parks, places that exist in large part to safeguard the animals within them. Consider Devils Tower National Monument, the surreal Wyoming butte considered sacred by Plains tribes. Made famous by the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, it annually hosts a group of travelers even more disruptive than aliens: bikers from the nearby Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. The roaring fleet of Harleys and Yamahas, Buxton has found, pushes prairie dogs back into their burrows, drives off deer, and deters bats from feeding near the monument for weeks. Had Spielberg’s extraterrestrials arrived mid-Sturgis, Richard Dreyfuss would have missed their five-note musical greeting.

IN HINDSIGHT, ROAD NOISE IN NATIONAL parks was a predictable problem. Nearly from their inception, America’s parks were “windshield wildernesses,” in the historian David Louter’s memorable phrase — road-trip destinations designed to be experienced from behind glass. In 2019, nearly 330 million people visited national parks, almost all in cars. That parks are being “loved to death” has become a truism, repeated as often as Wallace Stegner’s claim that they were the nation’s best idea. More visitation means more roadkill, more erosion along shoulders requisitioned as parking spaces, and, most of all, more noise. Nearly half the total area under the National Park Service’s jurisdiction today suffers at least three decibels of sonic pollution.

Noise, by contrast, is a human-produced pollutant, and, like its etymological root, nausea, it’s unpleasant.

To be sure, parks predated the automobile. Yellowstone National Park, America’s first, was established in 1872, and Yosemite, Mount Rainier, Crater Lake and others followed. But most were seldom visited, and then only by wealthy travelers who could afford cross-country train tickets and guided horseback adventures. Early visitors to Yosemite Valley had to chain their cars to trees and surrender their keys. Allowing automobiles, one visitor opined, would be akin to the serpent “finding lodgment in Eden.”

But the serpent was backed by powerful lobbyists, and pressure mounted to open parks to cars. Park infrastructure, though, was in no condition to accommodate them. Mount Rainier’s main road was so treacherous in 1911 that President William Taft’s aides worried that the commander-in-chief wouldn’t survive his visit. (Taft experienced no graver harm than getting stuck in the mud; his car, and his own substantial bulk, had to be hauled out by mules.) A few years later, Stephen Mather, a gregarious millionaire who had made his fortune hawking borax, toured Sequoia and Yosemite. Mather was smitten by his surroundings, but not the amenities. “Scenery is a hollow enjoyment to a tourist who sets out in the morning after an indigestible breakfast and a fitful sleep in an impossible bed,” he carped in a letter to the Interior Department. Came the reply: “Dear Steve, if you don’t like the way the national parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself.” And so, in 1917, Mather became the first director of the agency tasked with pulling America’s best-loved landscapes into a cohesive whole: the National Park Service.

Like its older sibling, the Forest Service, the Park Service had a murky mission. Its establishing legislation directed it to simultaneously conserve “wild life” and “provide for the enjoyment” of visitors but offered little guidance about how to reconcile those objectives. Mather made his priorities clear. Under his direction, the Park Service cranked out films, guidebooks and other propaganda; cozied up to the American Automobile Association; and finagled millions of dollars from Congress. By 1929, national parks were filigreed by 1,300 road miles, down which wheezed nearly 700,000 cars.

Mather’s ardor for auto-tourism was motivated by more than his desire for a hot breakfast and comfortable bed. His joviality concealed depression and perhaps bipolar disorder; for him, scenery offered better treatment than any sanitarium. Park roads, to Mather’s tumultuous mind, were egalitarian forces that permitted the old, young and infirm access to their scenic birthrights — a nationwide prescription for mental health.

Mather wasn’t entirely sanguine about his construction boom. A road through southeastern Yellowstone, he cautioned, “would mean the extinction of the moose”; today, that area is the farthest you can get from a road in the Lower 48, around 20 miles. Rather than building roads for their own sake, Mather believed in building the right roads, which to him meant monumental feats of engineering — Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park, Skyline Drive in Shenandoah, Generals Highway in Sequoia — that strove to harmonize with their spectacular surroundings. The epitome of his philosophy was Going-to-the-Sun Road, which the Park Service blasted from Glacier’s face with nearly a half-million pounds of explosives — a project so hubristic that three workers died during construction.

Mather’s grandiose roads showcased landscapes, but they trashed soundscapes, a form of degradation whose consequences would take decades to discover. “They’re built to be scenic, they’re built to be part of the experience,” Kurt Fristrup, a former Park Service bioacoustician, told me of the agency’s roads. “Ironically, that also means they’re built to project noise about as far as it can possibly be projected.”

MOST LAYPEOPLE TREAT THE WORDS sound and noise as synonymous. Yet they might more properly be considered antonyms. Sound is fundamentally natural, and tickles the ears in even the quietest places: the susurrus of wind, the drone of a bee, the starched snap of a jay’s wings. Noise, by contrast, is a human-produced pollutant, and, like its etymological root, nausea, it’s unpleasant. In the serenest landscapes, even an airplane can seem a violation.

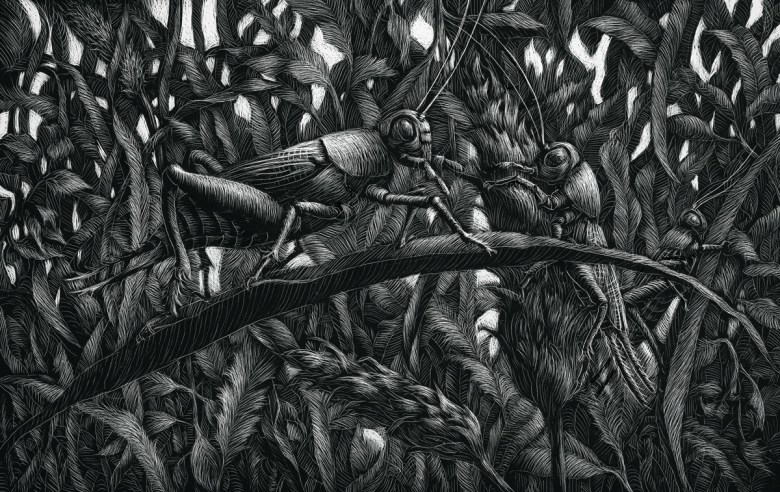

Noise is still harder on other species. Wild animals inhabit an aural milieu that is sensitive beyond our imagining. Human conversation occurs at around 60 decibels, and sounds that barely register to us — gentle breathing, the rustle of leaves — produce around 10 decibels. The most acute predators, meanwhile, can detect negative-20 decibels. Bats seize upon the crunch of insect feet; foxes triangulate snow-buried voles. Prey is equally perceptive. Scrubwren nestlings freeze at the footsteps of enemy birds. Tungara frogs duck at the flap of bats. While most animals sleep with their eyes closed, nearly all awaken at the snap of a twig.

Although organisms have always contended with loud environments, like blustery ridgelines and crashing waterfalls, cars have made cacophony more rule than exception. For animals that survive by the grace of their hearing, traffic’s “masking effect” can be fatal. Ambient road noise drowns out songbirds’ alarm calls and prevents owls from detecting rodents. A mere three-decibel increase in background noise halves the “listening area,” the space in which an animal can pick up a signal. By disturbing animals, noise also disrupts the ecological processes they catalyze, among them seed dispersal, pollination and pest control.

For all of its harms, the pave’s blab is difficult to study. In 2000, Richard Forman, road ecology’s paterfamilias, demonstrated that meadowlarks, bobolinks and other birds gave highways a wide berth, at least two football fields, and hypothesized that traffic noise was the “primary cause for avian community changes.” Yet roads were so transformative that it was hard to tease apart their perversions. Noise was likely repelling wildlife, yes — but perhaps animals also detested the sight of cars, or the abrupt forest clearing, or the impaired air quality. “People had been guessing that noise pollution was controlling animal distributions for a long time,” Jesse Barber, a sensory ecologist at Boise State University, told me. “But we needed to do an experiment” — to strip out the road’s many variables and isolate its sonic impacts.

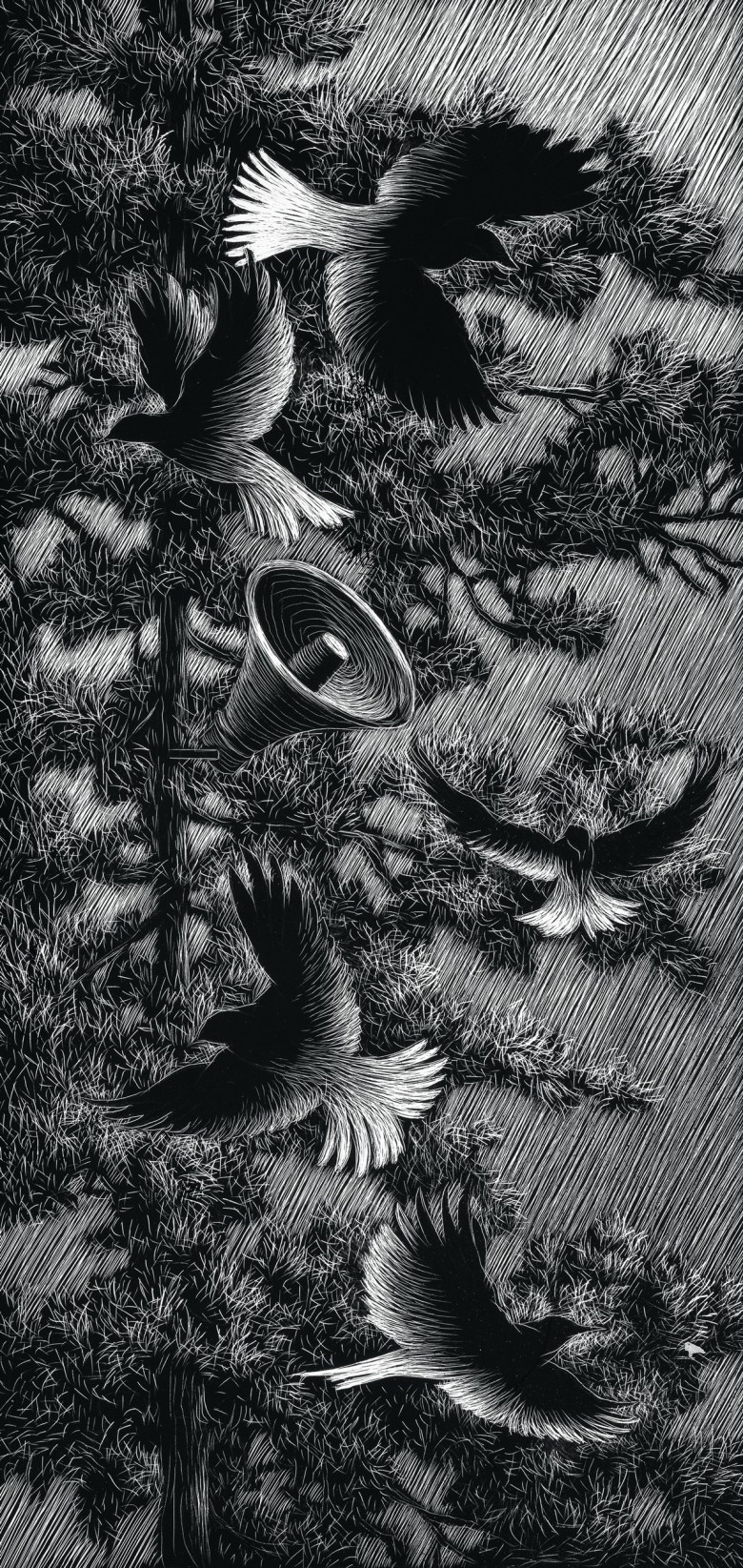

For the experiment’s site, Barber chose Lucky Peak, a green shoulder of land that rises above central Idaho’s sunburnt scrub. Every fall, rivers of southbound songbirds — lazuli buntings, hermit thrushes, golden-crowned kinglets — alight at Lucky Peak to refuel on berries and insects. The mountain is a superlative stopover owing partly to its paucity of roads; it’s an oasis in the desert of Boise-area sprawl. In 2012, Barber, a student named Heidi Ware Carlisle and some colleagues mounted 15 pairs of speakers and amps to tree trunks, wrapped the wires in garden hoses to deter chewing rodents, and shrouded them with shower curtains to keep off the rain. Then they blared a looped recording of traffic from 4:30 a.m. to 9:00 at night — a Phantom Road in a roadless wood.

The Phantom Road was so realistic it even fooled people. “We get hikers and mountain bikers and hunters through there all the time, and at least three times we ran into folks who were like, OK, I thought the highway was south of here, not east,” Carlisle told me. The birds were equally disoriented. On days when Carlisle played her recordings, bird counts plummeted. Some species, like cedar waxwings and yellow warblers, avoided the Phantom Road altogether.

And the Phantom Road didn’t merely drive off birds: It drained those who stayed. When Carlisle captured warblers and examined their tiny bodies, she found they were skinnier after they’d been near the Phantom Road. Songbirds survive by listening ceaselessly for the whir of falcons, the rustle of martens, and the alarm calls of their neighbors: “the chipmunk next door that sees the goshawk before you do,” as Carlisle put it. When road noise drowns out sonic cues, birds must look for predators rather than listen for them. This “foraging-vigilance trade-off” gradually depletes them: Every moment you’re scanning for hawks is one you’re not gobbling beetles.

Sound is fundamentally natural, and tickles the ears in even the quietest places: the susurrus of wind, the drone of a bee, the starched snap of a jay’s wings.

For the first time, researchers had shown that noise alone could impinge on animals’ lives. What made the experiment so compelling, though, wasn’t merely its ingenious design: It was where the Phantom Road’s noise came from. The traffic that played through Carlisle’s speakers hadn’t been recorded on an interstate highway or an urban boulevard. Instead, it was from Going-to-the-Sun Road, Glacier National Park’s 50-mile byway.

Going-to-the-Sun was a strategically chosen source for the Phantom Road. If noise tainted even a sanctuary like Glacier, where could birds feel comfortable? America’s windshield wilderness had extended acoustic pollution into its best-protected places. A dusky grouse in Rocky Mountain National Park was safe from hunters and developers, yet vulnerable to the growl of Winnebagos and Harleys — a conundrum not lost on the Park Service itself. “If you went to a freeway and said, ‘Hey, these trucks need to go slower because of the birds,’ well, there’s just absolutely no way that would happen, right?” Barber told me. “The parks are the places where we might actually be able to get some action. They’re getting slammed with traffic, they’re getting slammed with people, and the managers are willing to try something.”

Yet parks weren’t easily hushed. When Barber convinced the overseers of Grand Teton to temporarily cut speed limits in 2016, traffic quieted by a couple of decibels and visitors heard more birds. But the birds themselves still avoided the road. A car dawdling along at 25 mph might be softer than one cruising at 45, but it took longer to pass — a less acute stressor, but a more drawn-out one. It wasn’t hard to make park roads quieter, but it was exceedingly difficult to make them quiet enough.

“I think all of our work is pointing towards this: The best way to preserve quiet habitat for wildlife is to not build the damn road,” Barber told me. “And once you do, you’re in big trouble.”

Electric vehicles should help to an extent. Unburdened by the rattling gadgetry of internal combustion, their motors are virtually silent. But EVs are no panacea. Above 35 mph, tires, not engines, produce most vehicle noise. (The interstate’s monotonous drone is a blend of “rhythmic percussion” from rubber on road and “pattern noise” generated by air pockets popping within tread.) The Grand Canyon parking lot will be more pleasant without grumbling RVs, but electrification won’t silence the Everglades’ main highway, where the speed limit is 55 mph. And while “quiet pavements” — pitted surfaces whose divots dampen tire noise — showed potential when they were trialed in Death Valley National Park, their benefits diminish as grit clogs their pores. It’s hard to envision the Park Service scouring its roads with the “giant vacuum-cleaner-like device” some European cities deploy to maintain quiet streets.

Technology, then, holds few answers. And the Park Service, bound to appease visitors, seems unlikely to overhaul its windshield-wilderness model. But the number of windshields — well, that’s more malleable. In 2000, the agency banned private cars from much of Utah’s Zion National Park and replaced them with public buses. Rangers saw more deer and again heard the burble of canyon wrens echoing off sandstone. Since Stephen Mather’s day, the Park Service had bowed to cars, yet in several places it had cast out the serpent, or at least restricted its ingress. I decided to visit one such park myself — not Zion, but a wilder one, with a longer history of anti-car warfare.

THE DENALI PARK ROAD EPITOMIZES the tension that tugs at the Park Service’s heart. Its curvaceous 92-mile course is smudged with Stephen Mather’s fingerprints: In 1924, soon after construction began, Mather’s lieutenants urged builders to “avoid long straight lines” and showcase “the best possible views and vistas of the country.” From the start, the Alaskan weather and “bottomless” mud frustrated road crews, who earned poverty wages and lived in tent villages. Even so, luxury auto-tourists showed up in droves. Caravans of Studebakers ferried sightseers, clad in suits and pearls, 13 miles down the road to Savage Camp, where they slept in wood-framed tents and waltzed on a polished floor.

For decades, the Park Service continued to genuflect to cars. In the 1950s, the agency launched Mission 66, a massive construction program, co-sponsored by the American Automobile Association, that, among many other projects, would have paved and widened the mostly dirt Denali road. The scheme outraged Adolph and Olaus Murie, biologist brothers who argued that Denali was a place for deep thought, not cursory sightseeing. “The national park will not serve its purpose if we encourage the visitor to hurry as fast as possible for a mere glimpse of scenery from a car,” Olaus admonished.

The brothers won the battle, and the Park Service kept the road primarily gravel and dirt. In 1972 the agency, having gradually come around to the Muries’ way of thinking, announced an even more drastic policy. The unpaved portion of the road — 78 of its 92 miles — would remain off-limits to most private cars, forcing visitors to ride buses that crept along at 25 mph. The shift enraged the tourism industry, but the Park Service only piled on more restrictions. In 1986, it declared that just 10,000 or so vehicle trips would be permitted each year. Other parks were bursting at their seams, yet Denali had frozen its traffic.

“Today, we’re within a thousand vehicles of the number that went out onto the park road in 1986,” an ecologist named William Clark told me in 2019 when, after several hours of hitchhiking and walking on the Denali Park Road, I reached Denali headquarters. “I don’t know if there are many roads in the world that can say that.”

“The national park will not serve its purpose if we encourage the visitor to hurry as fast as possible for a mere glimpse of scenery from a car.”

Along with his colleague Dave Schirokauer, leader of the park’s research team, Clark — whose scruffy beard could adorn a gold prospector — is responsible for upholding Denali’s Vehicle Management Plan. The plan is particularly concerned with Dall sheep, snowy-fleeced ruminants that, from the road, appear mostly as pale pinpricks against distant outcroppings. Nimble, far-sighted and capable of surviving on lichen salad, they are exquisitely adapted for life among Denali’s promontories, where wolves can’t touch them. Each spring, though, sheep clamber down the talus to feast on grasses and wildflowers, a migration that the park road disrupts. In 1985, naturalists watched eight sheep inch cautiously downhill, “oriented toward the road, and displaying attention postures.” Over the next hour, the jittery animals advanced and retreated, ceding their progress every time a bus rumbled past, like sandpipers scuttling from a wave. Before long, wrote the naturalists, “the sheep had returned to the escape terrain,” their journey thwarted. Even minor increases in traffic, from 10 vehicles an hour to 20, can chase sheep from Denali’s roadside.

The park’s Vehicle Management Plan caters to sheep anxiety. It’s a quietly revolutionary document, permitting no more than 160 vehicles every 24 hours. Its most progressive provision is the “sheep gap,” a requirement that every hour, at several migration corridors, at least 10 minutes elapse without a single vehicle. “If there’s a band of sheep, or any wildlife, that are looking to make their move, they have their opportunity,” Clark said. “I describe it as a deep breath in traffic.”

Traffic, however, is inclined to hyperventilate. The near-universal goal of transportation officials is to fill service gaps, not create them. The sheep gap, Schirokauer acknowledged, is a “four-letter word” among many of the concessionaires who run Denali’s buses and hotels. “There’s incredible pressure on the park from the travel industry to allow more buses,” Schirokauer said. “Every time they add a wing to a lodge, there’s 80 new pillows. And they’re like, OK, that means we need two more buses a day to accommodate these people. People get when a theater is full, but they don’t get why a park road would be full. Until they get to a wildlife viewing stop, and there are 10 buses, and all they can see is the back leg of a bear.” I thought of all those tourists resenting other tourists for contaminating their solitude and remembered the rush-hour cliché: You don’t get stuck in traffic. You are traffic.

WHEN THE PARK SERVICE INSTITUTED the Denali shuttle in the 1970s, its goal wasn’t to cut noise pollution but to preserve the vague wilderness vibes that the Muries cherished. Yet the bus system has turned Denali into one of America’s finest soundscapes, a place that unmasks natural choirs rather than concealing them. In Denali’s symphony hall, nature plays strange, unrepeatable compositions — the song of warblers backdropped by a late-spring avalanche, say, like a percussion section pounding behind woodwinds.

One afternoon I drove the Denali road with Kate Orlofsky, a technician tasked with studying the bus system. We cruised through patchy forests that rolled toward scree. Cloud shadows scurried over the green-gold valley, a world without borders; a wolf could walk 600 miles from here without padding across another road. At Savage River, the end of the line for most cars, Orlofsky checked in with a ranger, who ticked a clipboard. We pressed on down dust and gravel, as the Muries had intended. A caribou browsed a gravel bar, swinging his velvety chandelier. “Sometimes I’ll have the windows down and listen to birdsong,” Orlofsky said, and I wondered where else that would be possible.

After a while, Orlofsky pulled over at a sheep-gap site and fished out a laptop. I scanned the mottled tundra: no sheep. We waited for buses to come so that Orlofsky could record their timing and confirm that the gap was being upheld. Soon, a dust plume rose in the distance, and a matte-green school bus chugged into view. Passengers gazed out the windows, fiddled with their cameras, or dozed, cheeks smushed against glass. Orlofsky tapped the laptop, and we got back in the car.

On the drive over, I’d asked Orlofsky about her past gigs trapping wolves, chasing pikas, and patrolling the Pacific Crest Trail. By comparison, I observed now, counting buses seemed, well, kind of boring. Orlofsky laughed. “It’s not the sexiest work. It’s not the most active,” she admitted. “But I can watch wildlife. I can enjoy the breeze.” When she wasn’t monitoring sheep gaps, her job entailed riding the bus system herself, a mole among the visitors, covertly recording data — about ridership, rest stops, wildlife, traffic — that would inform future iterations of the park’s vehicle plan. She was, in other words, a professional tourist, a luxury she didn’t take for granted. “People come from all over the world to do what I get paid to do,” she said. Denali has become what social scientists describe as a “near-wilderness,” a place where most visitors peer into the wild without immersing themselves in it. But a near-wilderness can still evoke ecstasy. Even ptarmigan, the pudgy grouse that is Alaska’s state bird, gets tourist cameras whirring. “People get pretty excited about ptarmigan,” Orlofsky said. “As they should.”

We’re so surrounded by road noise that we’ve compensated by deafening ourselves.

Months later, back home, I reread my notes from Denali. As I did, the muttering of an arterial and, below it, the sibilance of the interstate washed over me like acid rain. We’re so surrounded by road noise that we’ve compensated by deafening ourselves. Paging through my notes, I was appalled by their shallowness. “Birds,” I’d written, unhelpfully. “Wind.”

Natural sound is as salubrious as noise pollution is harmful. The crash of waves calms heart-surgery patients; the trill of crickets boosts the cognition of test-takers. Road noise both degrades our bodies and overwhelms the sounds on which we, like songbirds, depend. This, then, is the value of parks: as sonic sancta for wildlife and humans. When I spoke to the bioacoustician Kurt Fristrup, he described wandering with a friend one night through Natural Bridges, a national monument in the Utah desert. The hush was absolute, unmarred by traffic, and after Fristrup sat down, he became aware of his heartbeat thumping softly in the darkness. As he relaxed into silence, he heard another sound, eerie and magical: the heartbeat of the friend sitting beside him, its slow rhythm syncopated with his own.

Excerpted from Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet by Ben Goldfarb. Copyright © 2023 by Ben Goldfarb. Used by permission of Ben Goldfarb, care of The Strothman Agency, LLC. All rights reserved.

Ben Goldfarb is a High Country News correspondent and the author of Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. His next book, on the science of road ecology, will be published by W.W. Norton in 2023.Follow @ben_a_goldfarb

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline The Blab of the Pave.