The Rock Springs Massacre began with a fight between two Chinese and two white coal miners over the right to work a particularly desirable “room” in Mine No. 6. One of the Chinese men was stabbed in the skull. The white miners walked off the job, went home for their guns and knives, and hunted down the Chinese. Bodies tumbled into Bitter Creek, the wash that runs through the Wyoming town. Many Chinese fled into the sagebrush hills with little more than the clothes on their back. To ensure that the Chinese wouldn’t return, the rioters set fire to Chinatown. Any Chinese who had hidden in their cellars burned to death.

The labor struggle that led to the Rock Springs Massacre began years earlier, though. In November 1875, the Union Pacific Railroad, which owned the Rock Springs coal mines, brought Chinese laborers to Wyoming to break a strike. The white miners resented the Chinese as an alien race who took away white jobs and refused to assimilate.

As an immigrant living in the American West, I have long been fascinated by the wide-open landscapes and the stories they carry. The first time I drove through Rock Springs, long before I knew about the Chinese Exclusion Act and its entrails, I felt that the place was haunted. There is a Chinese belief that if the dead are not given proper burial rites, their spirits roam the land in search of their lost home. Maybe I had encountered these ghosts. And I began to wonder what it was like for the Chinese miners, living in the thick of that violent xenophobia — a legacy that continues today.

The white miners resented the Chinese as an alien race who took away white jobs and refused to assimilate.

The archives contain a lot of information about the Rock Springs Massacre, including the report from Union Pacific’s internal investigation, newspaper and eyewitness accounts, court and jail records, and correspondence between the company and Wyoming Territory officials. Notably absent is the Chinese perspective. In the poems on the pages that follow, from my project “Letters Home,” I conjure the persona of a Chinese miner who survived the massacre, speculating on what his perspective might have been. I drew on research as well as my knowledge of Chinese norms and beliefs to interrogate the fractures in the historical record.

— Teow Lim Goh

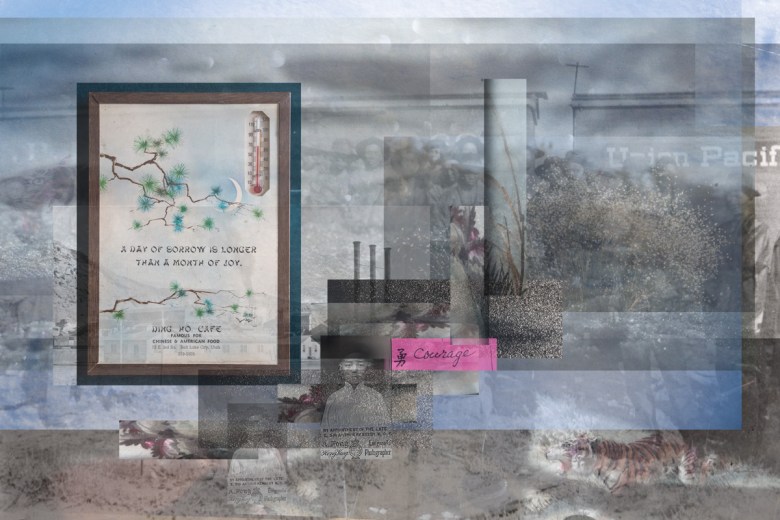

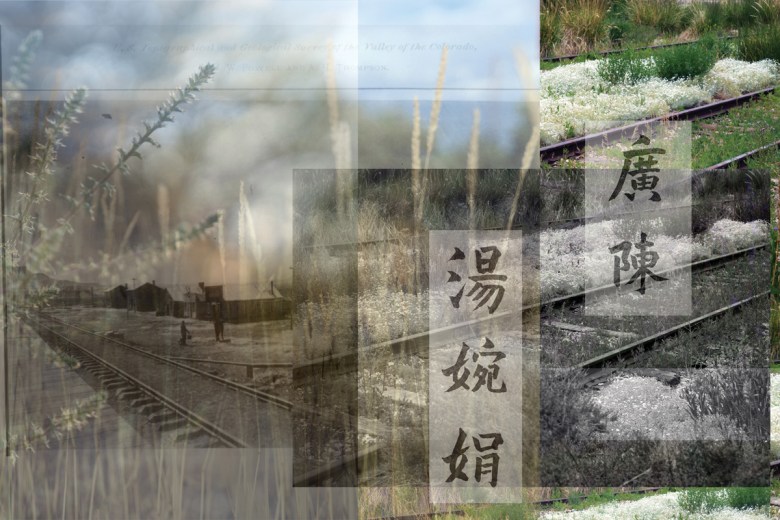

These images are an homage to my grandfather, Gung Gung, and to the Chinese miners of Rock Springs. Gung Gung, who humbly described himself as being “same as born in a restaurant,” was a brilliant, self-educated man — a poet, a photographer, a calligrapher, a community organizer, a businessperson and a family man.

My parents lived in Rock Springs briefly before I was born. When I was a child, we often visited Rock Springs and my grandparents’ trailer park. My dad’s family still lives there today. After two decades of absence, I returned to explore my family’s experiences and roots, as well as what it means to be biracial — both Chinese and white — in parts of the Intermountain West where diversity is scarce.

The Rock Springs Massacre of 1885 resonates in me today, with confusing feelings of where my biracial identity intersects — a liminal space, where I never quite feel like I fully fit in with either of my races.

This set of images works through the process of grief — rebuilding, peace and rebirth. I used historical images related to the event and overlaid them with family mementos, as well as with photos from my trips to Rock Springs. I intentionally left the images convoluted and dense to reflect my biracial identity and the human process of documenting history. The many layers represent how all the elements of ourselves — even the unwanted ones — work together to make us who we are.

—Niki Chan Wylie

December 1873

San Francisco, California

I don’t know why it is so difficult.

The railroad was hard work, but it was work.

We knew they paid us less than the white men,

but what could we expect? Debts we must pay.

Our families depend so much on us

to send back money. Now the railroad is done,

and the banks crashed four months ago, I swear

there is no work. I don’t know what to do.

Remember my old friend Ah Lum and all

the gold that he brought back from California,

the yellow silks he gave to his new wife,

the large brick home he built for his family?

Look at how well they eat, meat every day.

These days he hardly needs to work at all.

I want to build a paradise for us, too.

The railroad life is for young men. I thought

I could save up and go home, but there is never

enough. And I am not young anymore.

Dearest, I don’t know what I’m doing wrong.

December 1875

Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory

It’s a strange place out here. Not snowy

like the mountains

or stormy like the sea.

It’s a desert of broken rock.

And it is cold.

We live in wooden huts.

Winds seep through the cracks.

The white men are hostile.

I don’t know what happened, but soldiers

escorted us when we arrived.

Company guards protect us in the mines.

But I’m getting paid, finally.

Here’s my first paycheck, as I promised.

I don’t think I can stay here long, but the money is good.

I want to see you all again.

May 1882

Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory

And it has come to pass. Exclusion’s now

the law of this cursed land. At night I gaze

at the full moon and wonder when we can

share a pillow again. I thought that now

Mother is gone, you and the boys can join me

out here. But this barbaric law is aimed

at men like me. Laborers. Coolies. Slaves.

That’s what they call us. Only diplomats

and merchants can bring in their families—

if Father hadn’t died, if bandits hadn’t

ambushed the countryside, I would still be

beside you. And I might have finished school

and become a scholar. But it is useless

to dwell on the past. This is my lot now.

January 1885

Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory

I don’t want to make you worry, but I don’t know

who else I can tell. Last fall, the union

in Denver called for a strike in the mines. Here

in Rock Springs, they set fire to the machine shop

at Number One. In Carbon, the strikers

were all dismissed. Now they block the mines,

their guns square at their hips, threatening anyone

who would replace them. They’re still out there

in the biting cold of winter, demanding

the company dismiss us. They call us

a foreign menace. They’re full of themselves, but

maybe it’s time to go home. Yet I can’t stop thinking

of that year we didn’t even have rice to eat.

Historical images courtesy of the Sweetwater County Historical Museum and Library of Congress.

Niki Chan Wylie is an editorial and documentary photographer based in Salt Lake City, Utah. Stemming from her experiences and education in political science and environmental studies, she specializes in working with underrepresented communities.

Teow Lim Goh is the author of two poetry collections, Islanders (2016) and Faraway Places (2021), and an essay collection Western Journeys (2022).

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline Rock Springs Riot Revisited.