Yakama bands once gathered at Mool Mool springs in what is now Washington state to use the area’s bubbling waters for medicinal purposes. In 1855, the Yakama bands signed a treaty that ceded millions of acres to the United States in exchange for specific reserved rights. The next year, the U.S. Army built Fort Simcoe over a tribal campsite near the springs, and in 1860 established the Fort Simcoe Indian Boarding School there. It was the first boarding school built in the U.S., the beginning of an era marked by the forced removal, abuse and neglect of thousands of Indigenous children in several hundred similar institutions across the country.

“Educating was never an actual part of these schools,” said Theresa Sheldon, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribes and director of policy and advocacy for the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. “It was just the label to use for assimilation and colonization.”

“Educating was never an actual part of these schools.”

In October, Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson announced the appointment of five people from federally recognized tribes around the state to a newly formed Truth and Reconciliation Tribal Advisory Committee. The committee will investigate the state’s history of Native boarding schools — which Ferguson called “a shameful part” of Washington’s past — including at least 17 schools. A report of the committee’s findings is expected to be released in 2025, once the committee members have finished interviewing boarding school survivors and their descendants.

THE UNITED STATES is just starting to reckon with its long history of genocide. In May 2022, the Department of the Interior published a report listing 37 states where federally funded Indian boarding schools operated. The report gave eight recommendations for how the country can improve its relationship with tribal nations, including by encouraging Indigenous language revitalization, promoting Indigenous health research and providing support to non-federal entities who wish to release records in their care.

This comes as some state governments have begun working on their own truth and reconciliation projects, a process that has lagged in the U.S compared to other countries, such as New Zealand, Australia and Canada. Currently, California’s Truth and Healing Council is carrying out its own investigation into the state’s relationship with local Indigenous people, with a report expected to be released in 2025. That initiative follows reports released by Colorado in 2023 and Maine in 2015 that delved into boarding schools as well as into Indigenous people’s experiences in the state welfare system. The Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission — the first of its kind to examine Indigenous child welfare in the United States — uncovered cultural genocide and institutionalized racism in the state’s treatment of Wabanaki children.

The United States is just starting to reckon with its long history of genocide.

Asa K. Washines (Yakama Nation), a tribal liaison for the attorney general’s office, has been advocating for an investigation into Washington’s boarding schools for years. He said that the federal report is a good starting point but pointed out that there are “other things that were not included in that federal boarding school study that Washington can add.”

“We’re going on a truth-finding mission to figure out what to say, what Washington had in involvement, faith-based institutions had any involvement,” Washines said “This is just the beginning.”

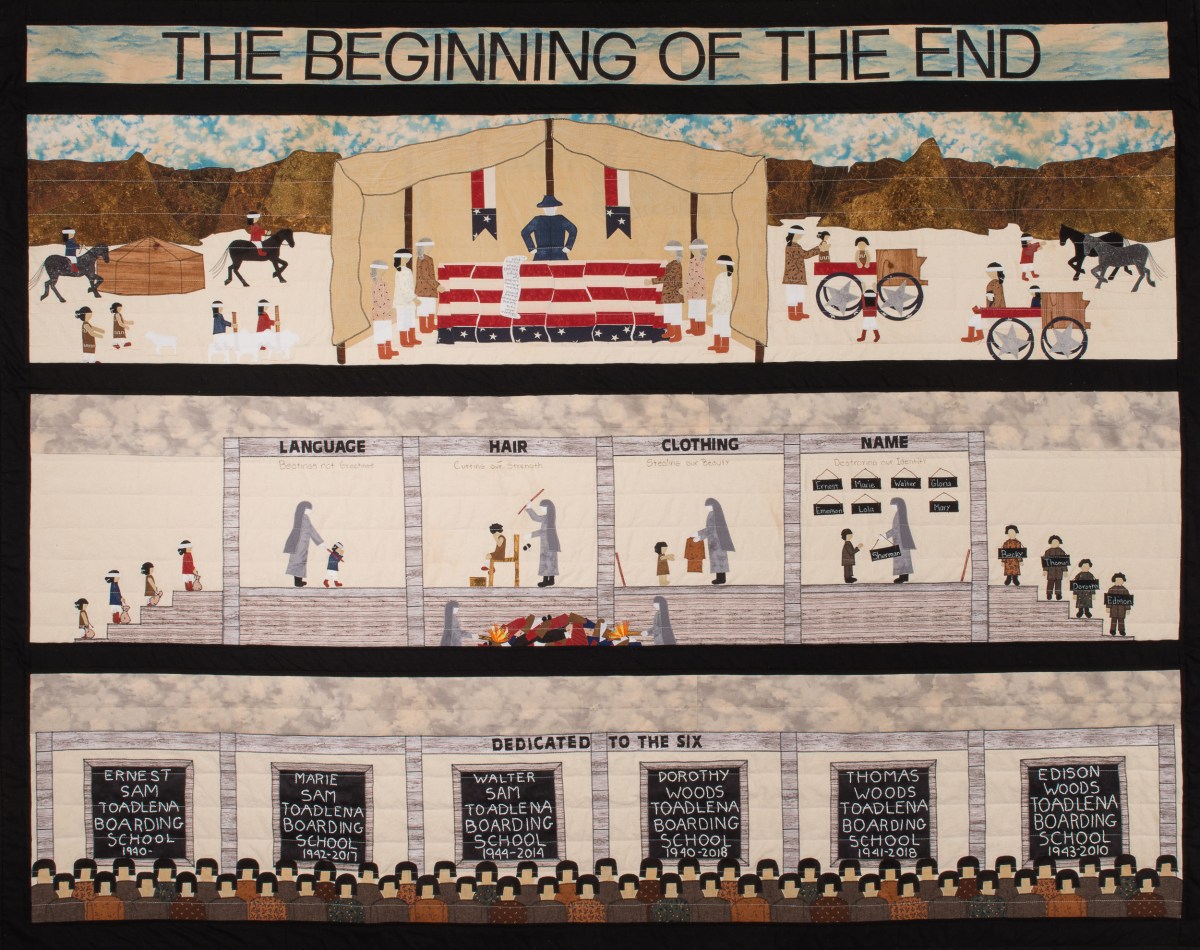

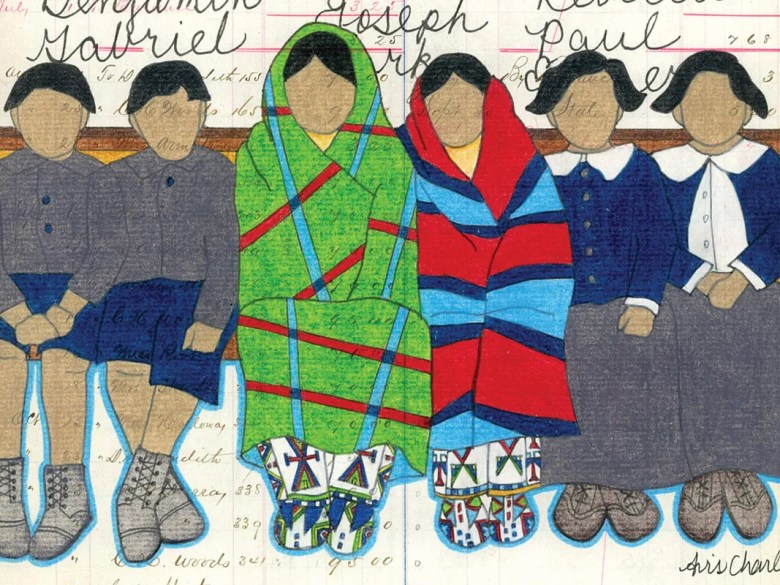

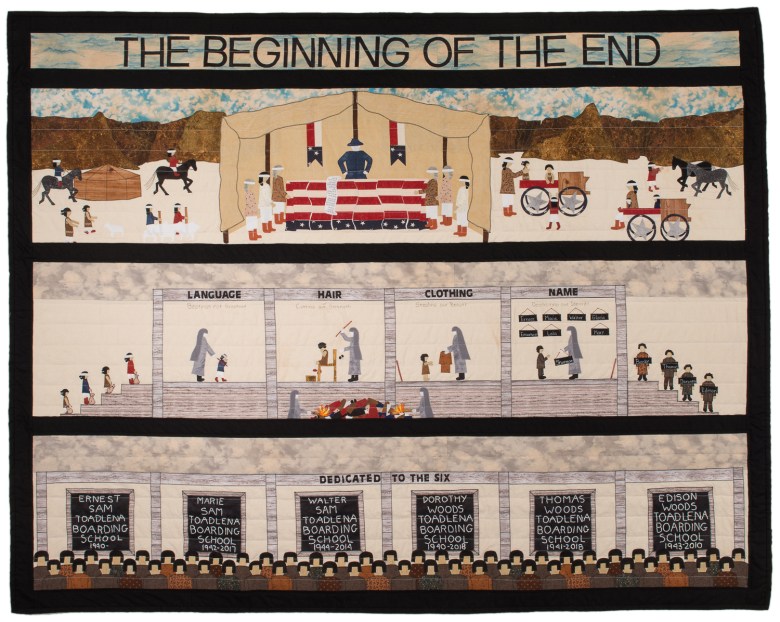

DESPITE THEIR STATED GOAL of educating Native children, the Washington attorney general’s office has acknowledged that corporal punishment, military drills and forced labor were all a part of life in the state’s boarding schools. The schools also prevented children from using their own Indigenous languages, religion and cultural practices in order to assimilate them more quickly into settler society.

The facts make it clear that these institutions were not designed to give Indigenous children a decent education. Edward A. Washines, a Yakama Nation citizen and advisory committee appointee who is himself a graduate of a boarding school, calls them “concentration camp schools.” “I do believe that trauma exists and that we can deal with it, but it’s gonna take a lot of work not only by our Indigenous tribes, but also by the United States government in trying to help us to provide the services that are needed for our families that are still affected.”

The impacts of these schools are still felt today in Washington, where Native students lag in reading proficiency and are about 20% less likely to graduate high school than white students, according to a National Indian Education Association 2022 report.

Washines, who would like to see increased federal funding for Native students in primary and secondary education and college scholarships, hopes the committee’s work can help achieve that. He also believes that the committee could help shape public school education through Washington’s “Since Time Immemorial” curriculum mandate since a high percentage of Indigenous youth attend public school in the state and deserve culturally competent education.

That mandate requires educational programs designed to teach students about local Indigenous culture and history. If the state is serious about requiring schools to teach about Indigenous people, Washines said, it needs to be honest about Washington’s historical treatment of them, too.

THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION Tribal Advisory Committee has no enforcement powers, meaning that the majority of its work is centered on community outreach and making recommendations to the state. Rebecca Black (Quinault), a committee appointee, sees this as an opportunity to fill the gaps between the state’s acknowledged history and Indigenous people’s own knowledge of the boarding school era. She got involved because she was intrigued by the attorney general’s office willingness to ask what genuine reconciliation could look like.

“It’s important that all of those be heard,” said Black. One challenge involves how to interview traumatized survivors with the courtesy and the respect that they deserve. “That’s part of our job, is to make sure that those spaces are Indigenized, and not colonized in their collection of data so we can provide a safe cultural space.”

The committee plans to hold listening sessions throughout the state at which Indigenous people will be invited to testify about their boarding school experiences. It is coordinating with other Indigenous leadership organizations to host sessions at conferences of the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board and Washington State Indian Education Association, among others.

“I believe that if we start speaking truth, and we move to healing, that we can then maybe start to build a healthy relationship,” explained Black. “We’ve been waiting 150 years for anyone to even acknowledge that these harms happened to our people, to our children.”

Shana Lombard is a High Country News intern. An enrolled member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, she lives in Tacoma, Washington.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.